IMAGING

WITH A DIGITAL SLR CAMERA AND

By

Maurice Gavin - http://www.astroman.fsnet.co.uk/

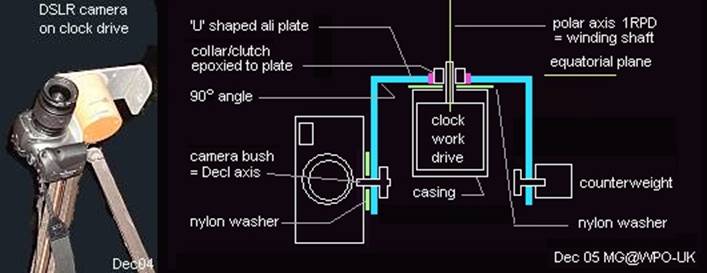

Many decades ago at an early Winchester

Weekend, I and a number of colleagues, bought for a few pounds 1 rev-per-day

surplus clockwork ‘motors’. Most got

converted to simple, if unique, star-trackers typically for Zenith cameras with

58mm fl f/2 Helios lenses. Mine, shown

below with camera attached, has survived with a new lease of life into the

digital age. It sits on my patio under

wraps [except for a bi-annual spray of WD40] and can be rapidly brought into

action in a matter of moments.

With care it accurately tracks a 135mm fl lens

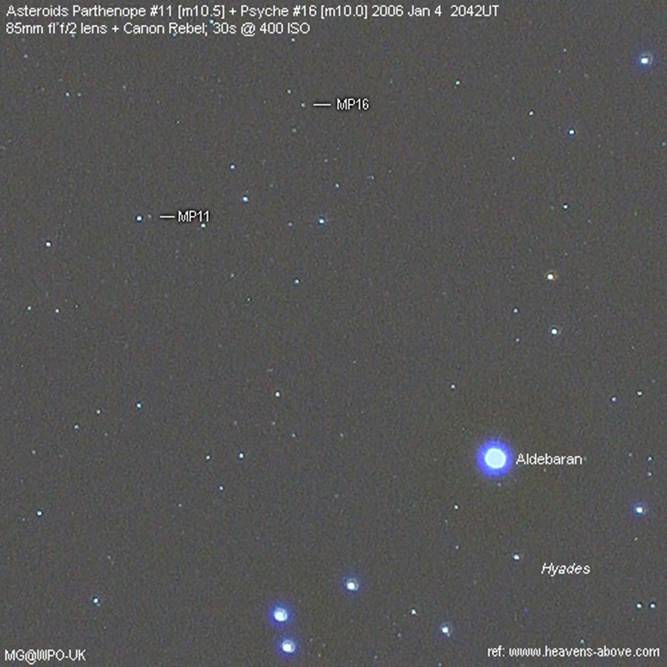

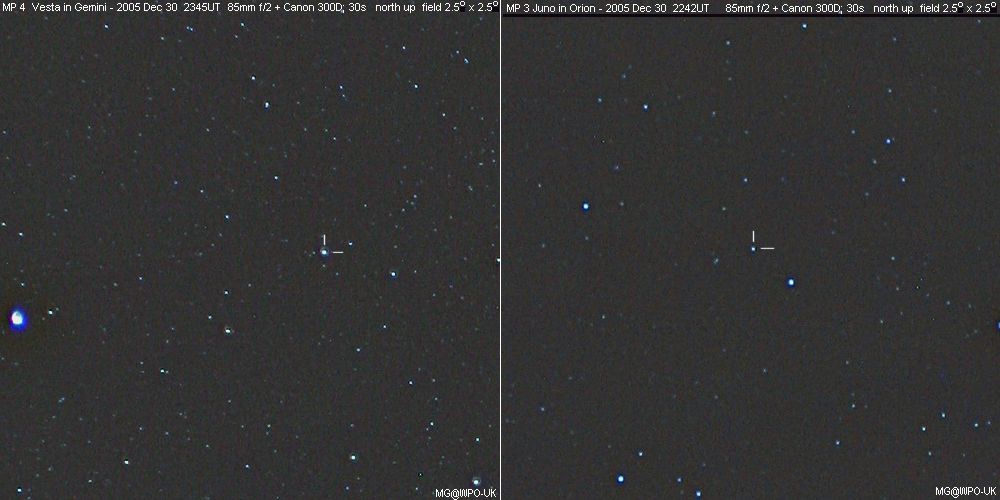

on my DSLR for about two minutes – adequate for my light polluted skies. Typically my favourite Jupiter 85mm fl f/2

Zenith lens reaches mag 11 in 30sec - sufficient for basic astrometry and

photometry of brighter asteroids.

Coverage via my APS sized detector equals half of Orion. The full-frame Canon 5D, for example, would

cover most of Orion with this same lens.

It’s the largest clear aperture, for a given exposure, that goes fainter

- not lens f/ratio. Fast f/ratios

attracts skyfog!

I don’t have any Canon lenses [except for the

standard zoom that came with my Canon 300D camera] but many-fixed focal length

Pentax screw/M42 thread lenses. A Kood

M42 to EOS adapter ensures a perfect fit and infinity focus at the lens

mark. Working in manual mode is no

disadvantage for astrophotography – in fact it’s preferable and more positive.

Some typical images are at the end of this

article and at http://home.freeuk.com/m.gavin/digsky.htm

. I also use my Minolta D7 digital

camera with fixed zoom 7.2 – 51mm lens on the drive to good effect. A cable [or delayed-action] release is

essential to avoid shake spoiling the exposure.

Due to my proximity to London, sky pollution

can be onerous and although special filters can reduce the problem they have

downsides and are not totally effective.

For a decade, using monochrome cooled CCDs, I was unaware of the true

colour of my local sky – digital colour leaves one in no doubt - it’s a hideous

yellow-brown. My solution was

simple. The selected raw image is

copied [via PaintShop Pro; Photoshop etc] as a separate image and heavily blurred

[Gaussian Blur] to ‘remove’ all the stars and then subtracted from the original

image. The yellow-brown sky turns a

pleasant neutral grey and ready for modest contrast stretching and sharpening

to a presentation image.

Does the title imply a sprung wound ‘motor’ is

unnecessary? I found that if the camera

and counterweight were imbalanced very slightly in favour of the camera [if

‘west’ of the meridian] then gravity alone was sufficient to cause the clock to

tick giving a controlled ‘fall’ to track the stars! I’m sure some of these motors are still

around and such a project is pleasantly free from mains/ battery power or leads

to trip over.