|

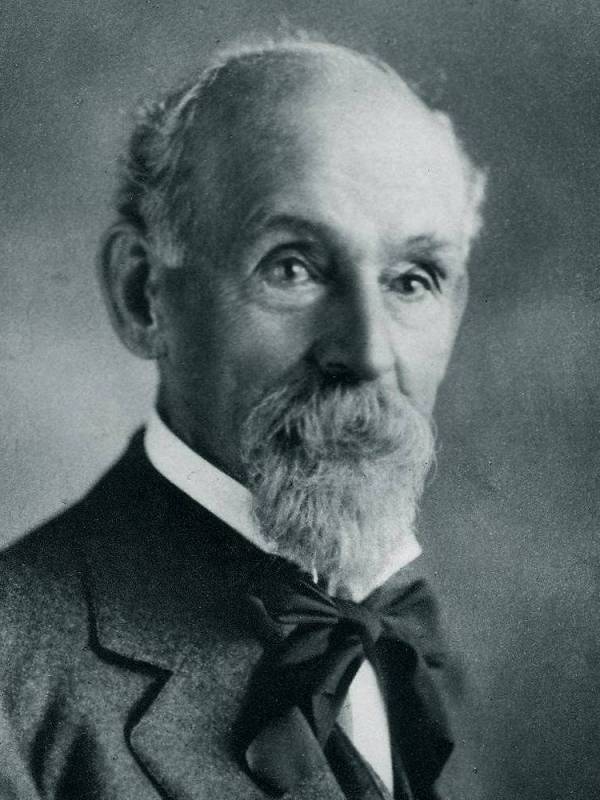

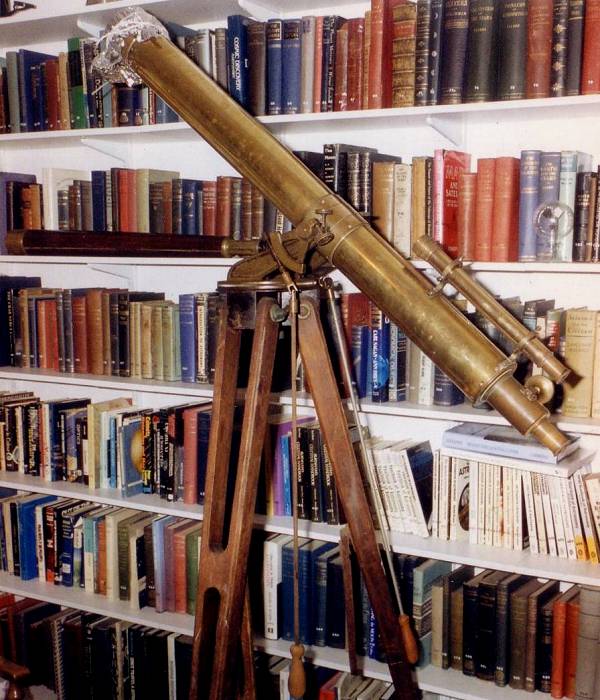

John Brashear and

the BAA R.

A. Marriott Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 125 (3) (June 2015), 175–6 |

|

John

Alfred Brashear (1840–1920).

The

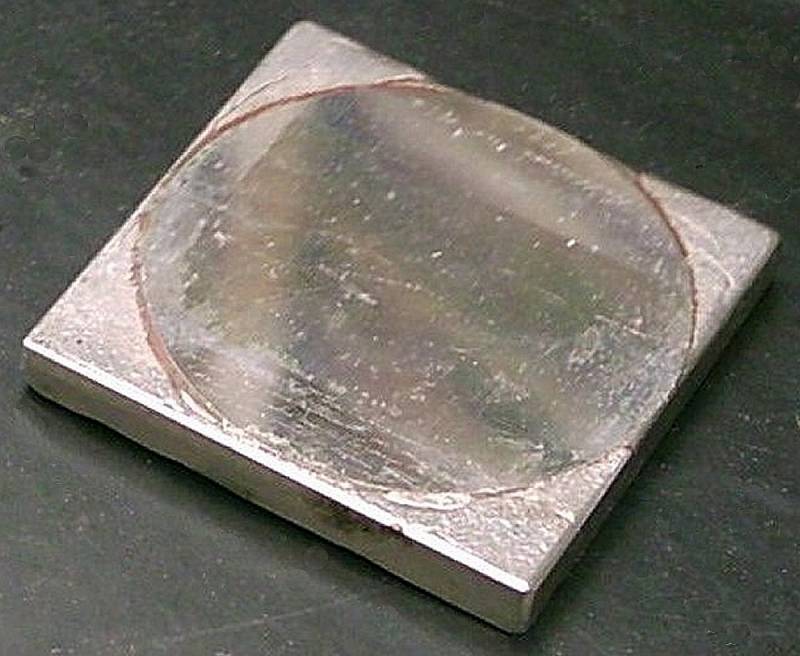

Brashear–Rowland grating: BAA instrument

no. 1. |

|

The British

Astronomical Association was founded in 1890 – officially on October 1,

though it was not until the first General Meeting on October 24 that the name

was finally established and the first Council elected. Among those who joined

before the end of that year – the Original Members – was the

instrument maker John A. Brashear, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1888

Brashear had toured the British Isles and Europe. He seems to have been

particularly impressed with British amateurs, and immediately he joined the

Association he presented a diffraction grating prepared at his own works and

ruled on the engine designed by Henry A. Rowland, professor of physics at Johns

Hopkins University, Baltimore. Brashear prepared the plates for these

gratings, which were made of speculum metal [1] (an alloy of copper and tin)

because much finer lines could be produced than could be engraved on glass.

The engine was at first designed to rule about 43,000 lines per inch, but

Rowland afterwards determined that better results could be obtained with

14,438 lines per inch, which he defined as his standard. ‘The success

of the ruling engine’, Brashear wrote later, ‘depended on the

geometrical perfection of the surfaces of the speculum-metal plates to be

polished. They required not only a very high polish, but a very accurate

surface; say, no error of one fifth of a light wave, or approximately, one

two-hundred-thousandth of an inch.’ [2] Over many years, Brashear was

the sole supplier of the finished plane and concave gratings, which were

‘sought by every physical laboratory in the world.’ During

Brashear’s second visit to Britain in 1892 he spoke at the

Association’s meeting on April 27. [3] Later, he described the

Association as an organisation which had in its membership: ... many amateurs who

loved astronomy, but who worked at regular vocations, some of which were of

menial character, but if they had done good work in adding to the sum of

knowledge in the beautiful science of astronomy, they were honoured and

received as kindly as if they were the greatest moguls of the country. I

think that scientific men respect the work of enthusiastic amateurs, if that

work is done in a conscientious, careful manner.’ [4] From

1890 to 1936 the grating was used successively by John Evershed, Walter

Maunder, and Charles Butler. In 1952 it was placed on loan to another Member,

but a few years later he disappeared and the grating was written off as lost.

Then, in 2004 I received a letter from that same Member, informing me that he

wanted to return the grating and that he would be moving to Cyprus at the end

of that week. So, I immediately travelled to the south coast and recovered

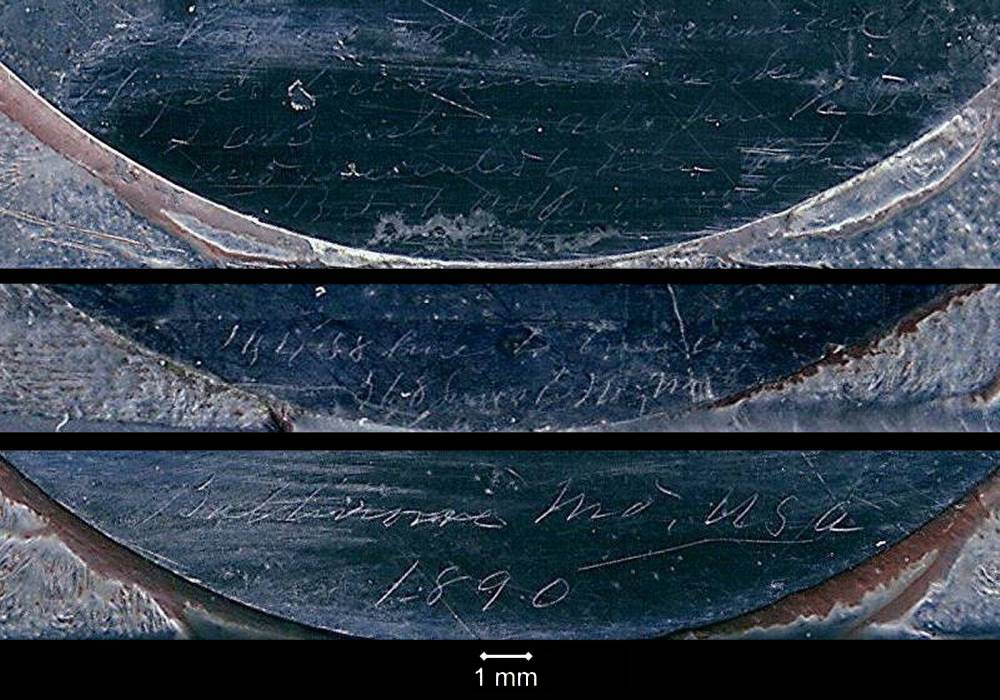

it. It measures 36 x 36 mm with a ruled area 29 x 21 mm, and is inscribed:

‘Ruled on Rowland’s Engine. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,

Md. U.S.A. 1890. Plate prepared at the Astronomical and Physical Instruments

Works of J.A. Brashear, Allegheny, Pa., U.S.A., and presented by him to the

British Astronomical Association. 14,438 lines to one in. 568 lines to mm.

A.E. Decemb. 10, 1890.’ This grating – later designated

instrument no. 1 – is not only an early example of a new technology; it

is a tangible record of international recognition of the Association

immediately it was founded. Historically, it is the Association’s most

important and valuable instrument. |

||||

|

The inscription on three sides of the upper face of the

grating. |

|

In the early

years of the Association there was no intention of forming an instrument

collection, and they were not numbered until several years later. [5] Only

two other instruments by Brashear have been presented: no. 64, a

3½-inch refractor presented by the family of H. P. Thompson in 1937;

and no. 209, a 5-inch object-glass presented by D. Cassels Brown in 1959. The

object-glass was lost within a few years, while the refractor was loaned to a

school in Lancaster in 1946 and disappeared several years later. In 1985,

however, Denis Buczynski found the refractor and rescued it from that same

school. It had not been used for many years and required restoration, so

Denis therefore retained stewardship of it until a decision could be made

concerning its future. We discussed this on several occasions, and following

his suggestion we eventually decided that it would be ideal if it were to

find a home with a dedicated specialist and that I should propose to Council

that it be presented to Bart Fried, founder and President of the Antique

Telescope Society. This organisation is based in New York and has an

international membership which acts as a link between numerous enthusiasts,

researchers, collectors, and users of classic telescopes, and presentation of

the Brashear telescope offered an opportunity for developing international

relations. After Council agreed to this proposal in January I wrote to Bart

to inform him of the decision, to which he replied: ‘What can I say but

that I accept! It’s very kind and you can be sure that it will be well

cared for and definitely used.’ |

||||

|

Bart had

already arranged to visit Denis during his travels around England and

Scotland in March, and I therefore asked Denis to act on my behalf (as

Curator of Instruments) as representative of the Association by formally

presenting the instrument to Bart during his visit. This short ceremony took

place at Denis’s home on March 20 (the day of the solar eclipse). A few

days later I showed the Brashear grating to Bart when I met with him at

Richard McKim’s home, where we spent a very pleasant and enjoyable few

hours. Bart has since sent a letter of appreciation addressed to

the President, Officers, and Members of the British Astronomical Association: This

is an especially prized gift, because I have been researching the life and

work of Dr Brashear since 1985 and I collect Brashear memorabilia. Fortunately,

this telescope has suffered minimally over the years. The optics are in good

shape, and it will be a labor of love to restore it to its original

condition. More importantly, it will be used. There are very few remaining of

this particular model refractor, but a notable example is now on display at

the South Carolina State Museum, in the Robert Ariail Collection. That one

will be a good example to help with the restoration of ‘The BAA

Brashear’. Uncle John, as Brashear was commonly known around Pittsburgh,

was a good friend of the BAA, and he gave the Association a gift of a small

presentation Rowland–Brashear diffraction grating – one of the

products that earned him fame with astronomers throughout the world. It is

still in your collection, and Bob Marriott proudly showed it to me during my

visit. So I give my heartfelt Thank You to my friends in the British

Astronomical Association, for the wonderful hospitality given during my visit

and for the very kind gift of the Brashear telescope. |

|

The Brashear 3½-inch refractor. |

||||

|

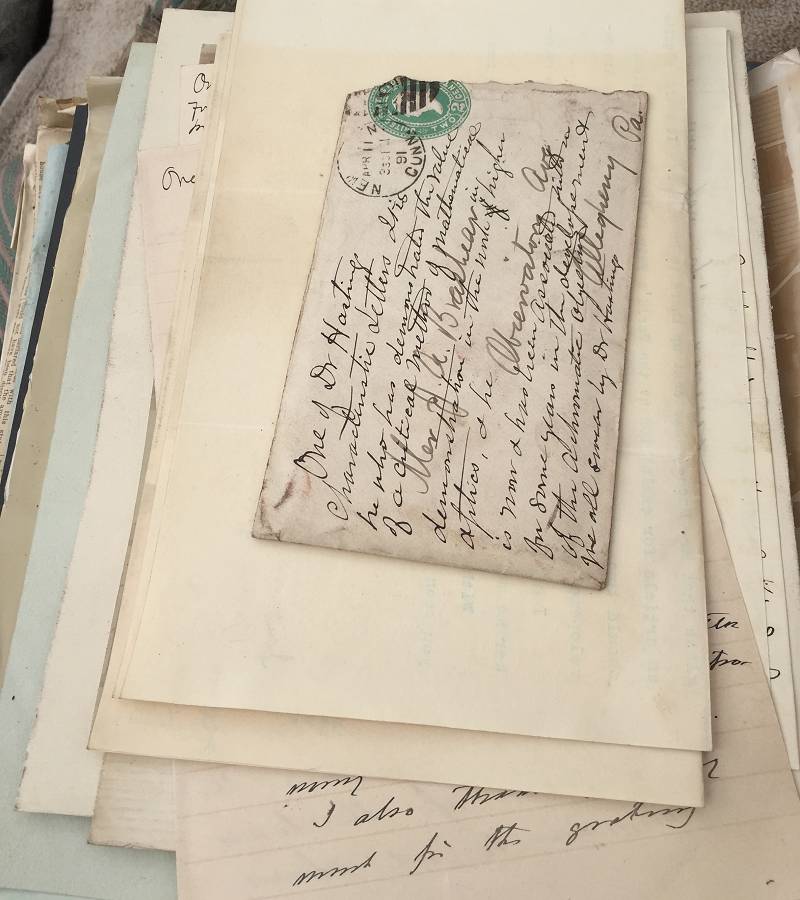

Brashear’s factory, built in 1886, was an important building

in the history of Pittsburgh and was listed in the National Register of

Historic Places. In March, however, one of the walls collapsed and the

building was considered unsafe. During the demolition, a sealed brass box was

discovered in the foundations. This time capsule, opened on March 24, was

found to contain several dozen letters, documents, photographs, and other

memorabilia. Bart Fried has since examined this collection, which includes a

letter from Sir Howard Grubb to Brashear, congratulating him on the

establishment of his factory, stating that he was pleased to sponsor

Brashear's membership of the Association (Grubb served on the first Council),

and suggesting that they might find common ground to work together on

projects – a mark of international cooperation and friendship. With the

remarkable coincidence of this unexpected find, it seems appropriate that 125

years after Brashear’s gift to the Association, one of his instruments

should return home. Notes

and references 1 Speculum metal was used for telescope mirrors from the time

of Newton’s telescope until the advent of silver-on-glass mirrors in

the mid-nineteenth century. The gratings were expensive, so few amateurs

could afford them. In 1898, Thomas Thorp – a Member of the Association

– announced his invention of the replica grating consisting of a cast

produced from a thin solution of celluloid in amyl acetate. Thorp designed

various instruments, including telescopes and spectroscopic equipment, and

also invented and designed the first coin-slot gas meters, |

|

Bart

Fried (left) receives the Brashear refractor from Denis

Buczynski. (Frame from a video recording by David Storey and Glyn Marsh.) |

|

|

2 W. L. Scaife (ed.), John A. Brashear: The Autobiography of a

Man who Loved the Stars. New York: The American Society of

Mechanical Engineers, 1924, p. 75. 3 ‘Report of the Meeting of the Association

held April 27, 1892’, Journal of

the British Astronomical Association, 2 (1892), 319–21. |

4 5 |

Scaife

(ed.), Autobiography, p. 120. R. A. Marriott, ‘The BAA observatories and

the origins of the instrument collection’, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 117 (2007),

309–13. |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ Al Paslow was present when the time capsule was opened on

March 24, and a selection of photographs of the contents can be

viewed on his website |

|

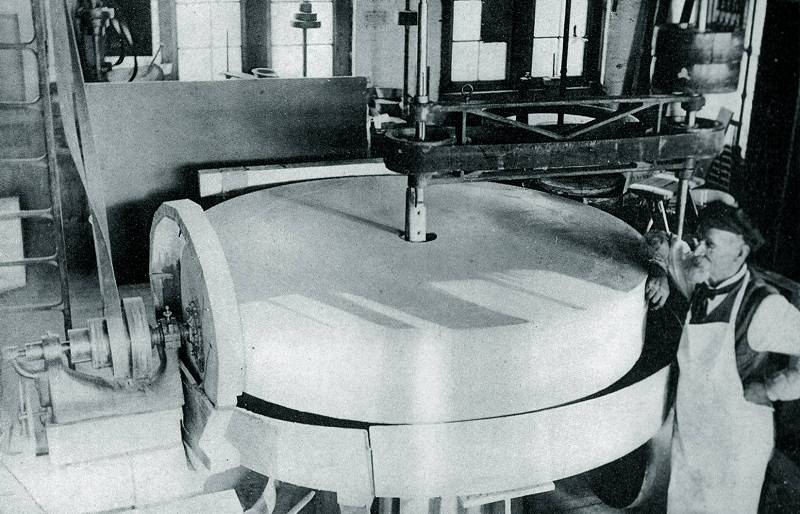

_______________________________________________________________ Rough-grinding the 72-inch mirror for the Dominion

Astrophysical Observatory

|

|

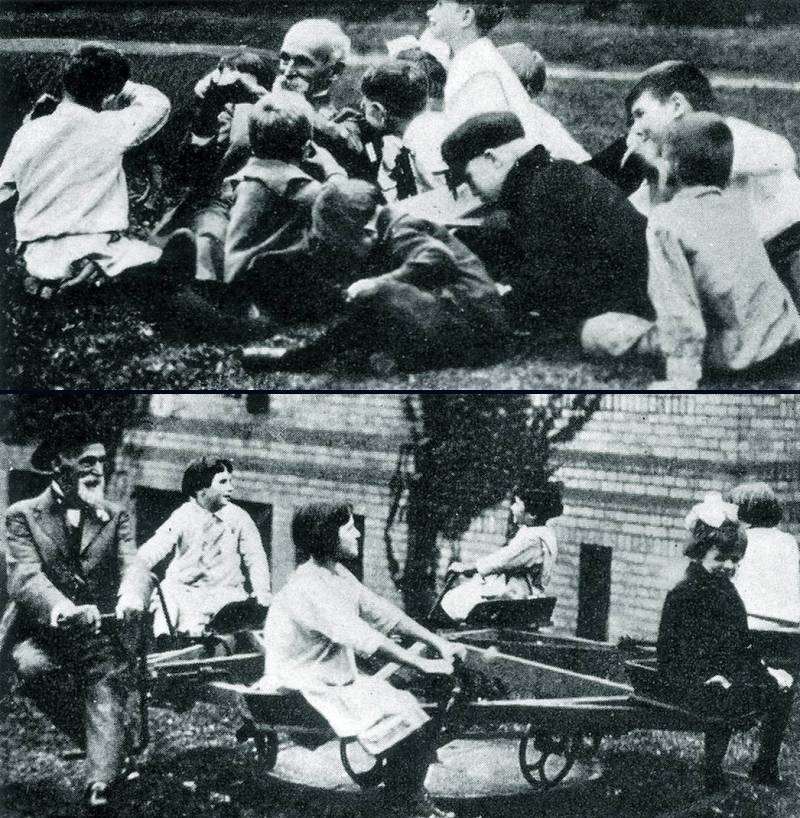

_______________________________________________________________ W. L. Scaife, the editor of Uncle John’s

autobiography, writes in the Foreword: ‘There was a genius other than mechanical which made

John Brashear Pennsylvania’s best-loved citizen, the intimate of

millionaires and paupers, of scientists, educators, and untutored workmen, the

friend of the newsboy, the natural, easy playmate of little blind

children. It was the genius of a rare personality.’

|

|

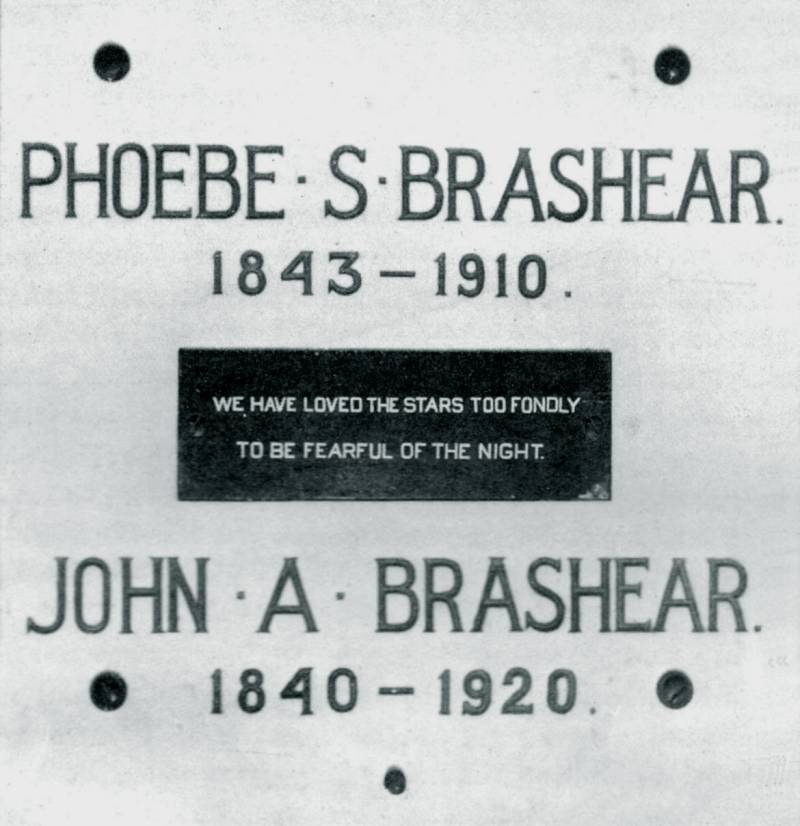

_______________________________________________________________ A literary countermeasure against ‘security’

lighting: the epitaph on the memorial to Brashear and his wife at Allegheny

Observatory ...

This is the slightly modified last line of ‘The Old

Astronomer to His Pupil’ by the English poetess Sarah Williams (1837–1868): Reach me down my Tycho Brahe, I would know him when we

meet, When I share my later science, sitting humbly at his feet; He may know the law of all things, yet be ignorant of how We are working to completion, working on from then to now. Pray remember that I leave you all my theory complete, Lacking only certain data for your adding, as is meet, And remember men will scorn it, ‘tis original and

true, And the obloquy of newness may fall bitterly on you. But, my pupil, as my pupil you have learned the worth of

scorn, You have laughed with me at pity, we have joyed to be

forlorn, What for us are all distractions of men's fellowship and

smiles; What for us the Goddess Pleasure with her meretricious

smiles! You may tell that German College that their honour comes

too late, But they must not waste repentance on the grizzly savant's

fate. Though my soul may set in darkness, it will rise in

perfect light; I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the

night. |