2013 September 21

The November Sky

With the onset of dark nights and the possibility of a bright comet, there is plenty to capture the attention of the amateur astronomer over the coming months.

In the east the winter favourites of Orion and Gemini have cleared the horizon giving a reminder, if it were needed, that shirtsleeve observing is over for another year. The Hunter contains two stars, both much larger than the Sun, in the form of Alpha and Beta Orionis, better known to us as Betelgeuse and Rigel. Despite their Greek alphabet designations, Rigel is in fact the brighter of the two at magnitude +0.12 and is part of a triple star system. It is a blue supergiant with a radius in the order of 75 times that of the Sun. Betelgeuse, varying between magnitudes +0.2 and +1.2, is much larger still with a diameter some 1,000 times that of our own star. Above Orion lies Taurus containing two of the best known open clusters, the Hyades and the Pleiades with the later being far more photogenic than the former. It used to be thought that the hot blue stars of the Pleiades had formed in the nebulosity that we see around them but we now know that the star group is merely “passing through” that part of the interstellar medium. The Hyades, despite being much less likely to attract the amateur astro-photographer, have been the subject of a number of studies that have broadly agreed that their distance from us is in the order of 150 ly.

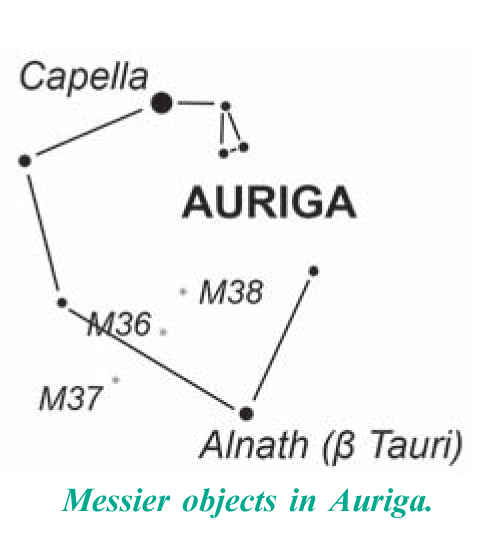

The brilliant Capella is now nearly 70° in altitude and on its way to pass close to the zenith in early January. On the subject of open clusters Auriga contains three; M36, M37 and M38 with visual magnitudes of 6.3, 6.2 and 7.4 respectively. Also just visible to the naked eye from a really dark site is M34, another open cluster than lies just within the borders of Perseus.

Looking to the south we see that Pegasus has just passed the meridian, but M31 lies almost upon it and only 10° from the zenith. It is of course a favourite with imagers along with its two brightest satellite galaxies M32 and M101, both of which are thought to have had some degree of interaction with their much larger neighbour. Below The Square is the most obvious part of Pisces known as the “Circlet” forming the head of one of the fishes and made up of five, third and fourth magnitude stars. The head of the other fish sits below Andromeda and is less well defined. Due to the effects of precession, the Vernal Equinox currently lies in Pisces although it is gradually drifting towards Aquarius. Low down and just west of the meridian is the brightest star in Pisces Austrinis – Fomalhaut – that in mythology is said to represent the mouth of the southern fish. It is one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations. Just to the east of Fomalhaut lies the small and rather faint group of stars that make up Sculptor which seems to have no claim to fame other than it is the location of the south galactic pole.

Looking to the south we see that Pegasus has just passed the meridian, but M31 lies almost upon it and only 10° from the zenith. It is of course a favourite with imagers along with its two brightest satellite galaxies M32 and M101, both of which are thought to have had some degree of interaction with their much larger neighbour. Below The Square is the most obvious part of Pisces known as the “Circlet” forming the head of one of the fishes and made up of five, third and fourth magnitude stars. The head of the other fish sits below Andromeda and is less well defined. Due to the effects of precession, the Vernal Equinox currently lies in Pisces although it is gradually drifting towards Aquarius. Low down and just west of the meridian is the brightest star in Pisces Austrinis – Fomalhaut – that in mythology is said to represent the mouth of the southern fish. It is one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations. Just to the east of Fomalhaut lies the small and rather faint group of stars that make up Sculptor which seems to have no claim to fame other than it is the location of the south galactic pole.

In the west the three bright stars of the Summer Triangle are still on show although part of Aquila has already set. The brightest star in the Swan may well be Deneb at the tail but surely much more pleasing to the eye is the lovely double star Albireo that signifies the head. It is made up of blue and yellow components, the latter of which is itself a binary. Within the boundary of Cygnus lie a number of open clusters, the brightest of which are M39 at magnitude +4.6 and NGC6871 at magnitude 5.2.

Towards the north the larger of the two bears is just beginning to climb away from the horizon whilst its smaller namesake points downwards towards it. Draco is still well positioned if you want to follow its twists and turns between Ursa Major and Minor. The head of the dragon lies close to both Hercules, which is now setting, and the bright star Vega. Cassiopeia is on the meridian and close to the zenith with Cepheus to her west and Camelopardalis to her east. The latter is one of several faint constellations that lie close to the celestial pole, the other being Lynx. Camelopardalis is the 18th largest by area in the sky despite having no stars brighter than magnitude 4, although it does boast of the asterism Kemble’s Cascade. This is a straight line of twenty stars that cover approximately five Moon diameters, and range in magnitude between 5 and 10. They are named after the Franciscan Friar who found them whilst scanning the sky with binoculars.

| New | First Quarter | Full | Last Quarter |

| Oct 5 | Oct 11 | Oct 18 | Oct 26 |

| Nov 3 | Nov 10 | Nov 17 | Nov 25 |

Planets and dwarf planets

Mercury reaches greatest eastern elongation on October 9, but despite being 25° from the Sun it will be unsuitably placed for observation as seen from the UK. As an example, on that date, the planet will have set before the Sun is 6° below the horizon. By contrast after Mercury has passed through inferior conjunction on November 1, it moves west of the Sun and reaches greatest western elongation on November 18 to provide us with the best morning apparition of 2013. On that date the innermost planet will be just over 10° above the south eastern horizon when the Sun is still 6° below it. Its magnitude increases up to, and beyond, elongation reaching a maximum of -0.7.

Venus remains low in the south west, and south-south-west later, during much of this apparition. The poor showing of Mercury is for the same reason as that for Venus – the proximity of the ecliptic to the horizon during the evenings at this time of year. At the start of the period Venus is 4° high at the end of civil twilight whilst by the end of the period, as the angle of the ecliptic increases, the planet is 11° high in the same twilight conditions. As the year progresses Venus draws in towards the Sun as it approaches inferior conjunction in January 2014.

Mars is still a morning object, that spends most of the period in Leo, although towards the end of November it moves east into neighbouring Virgo. As nautical twilight ends at the beginning of October Mars is already at an altitude of 35°, meaning that it rises 4½ hours ahead of the Sun. By the end of the period the planet lies, in angular terms, over 70° from our parent star, by which time it will rise less than an hour after midnight. During October and November the Red Planet increases in apparent diameter from 4.8 to 5.5 arc seconds, improving things slowly but surely for CCD imagers.

Jupiter is an evening object as the period begins, rising around 22.30 UT. By the end of November this has become 18.40 UT meaning that the planet is still 30° high in the morning twilight when the Sun is 6° below the horizon. During the period the planet’s apparent equatorial diameter increases from 38 to 45 arc seconds, a process which continues for the remainder of the year. Its brightness also increases marginally from -2.2 to -2.5. Jupiter spends the whole of October and November in Gemini and reaches its first stationary point on November 7 after which it moves retrograde (east to west).

Saturn is edging gradually into the twilight and will be difficult to spot low down in the west-south-west at the beginning of October when it will be only 5° in altitude at the start of nautical twilight.

It is quickly lost in the solar glare and suffers a conjunction with the Sun on November 6. After that it becomes visible again during December as a morning object at magnitude +0.6.

Uranus reaches opposition on October 3 when its magnitude will be +5.7 and its apparent diameter will be 3.7 arc seconds. It lies on the Pisces/Cetus border and remains there for the entire period.

Neptune spends this part of the year in Aquarius at magnitude 7.8. Although it is moderately well placed it is never as much as 30° above the horizon when it culminates. By the end of November it sets at 22.30 UT.

1 Ceres and 4 Vesta are both morning objects in Leo rising approximately 2½ hours ahead of the Sun. They move very much in unison eastwards from Leo into Virgo and by the end of the period they rise at 01.30 UT.

Meteors

There are three well known showers, the Orionids, the Taurids and the Leonids, that are active during October and November.

The Orionids are active from October 16 to 30 with a broad peak from the 21 to 24. At maximum the ZHR could reach 25, and although the radiant rises just after 21.00 UT, the waning gibbous Moon will seriously interfere with observations.

|

Date |

Time |

Star |

Mag |

Ph |

Alt ° |

% illum. |

mm |

|

Oct 9 |

17.36 |

ZC 2456 |

6.3 |

DD |

15 |

25 |

70 |

|

Oct 11 |

18.38 |

ZC 2787 |

6.3 |

DD |

19 |

48 |

50 |

|

Oct 13 |

23.06 |

Nu Aquarii |

4.5 |

DD |

13 |

72 |

40 |

|

Oct 23 |

22.57 |

ZC 886 |

6.8 |

RD |

26 |

77 |

80 |

|

Oct 24 |

23.37 |

26 Geminorum |

5.2 |

RD |

25 |

68 |

40 |

|

Oct 26 |

00.43 |

68 Geminorum |

5.3 |

RD |

26 |

59 |

40 |

|

Nov 2 |

06.04 |

Spica |

1.0 |

RD |

4 |

2 |

40 |

|

Nov 7 |

16.52 |

SAO 161842 |

6.9 |

DD |

18 |

22 |

70 |

|

Nov 7 |

17.36 |

ZC 2733 |

6.8 |

DD |

15 |

22 |

50 |

|

Nov 10 |

19.16 |

46 Capricorni |

5.1 |

DD |

19 |

56 |

40 |

|

Nov 22 |

00.23 |

Lambda Geminorum |

3.6 |

DB |

42 |

83 |

150 |

|

Nov 22 |

01.14 |

Lambda Geminorum |

3.6 |

RD |

48 |

83 |

40 |

|

Nov 23 |

05.23 |

ZC 1237 |

6.5 |

RD |

49 |

74 |

70 |

|

Nov 24 |

02.00 |

60 Cancri |

5.4 |

RD |

39 |

66 |

40 |

The Taurids last from October 20 until November 30 with maxima on November 5 and 12 when the ZHR is expected to be 10. The thin crescent Moon presents no problems for the first maximum, but may interfere with the second as by then it is gibbous. On November 12 the radiant culminates a little after midnight which is also the time that the Moon sets.

The Leonids reach maximum on November 17 at 19.00 hrs with shower activity lasting from November 15 to 20. The radiant lies within the “Sickle” and at its most productive could achieve a ZHR of around 20.

The bad news is that peak activity coincides with full Moon.

Lunar Occultations

In the table I’ve listed events for stars down to magnitude 7.0 although there are many others that are either of fainter stars or those whose observation may be marginal due to elevation or other factors. DD = disappearance at the dark limb, whilst RB = reappearance at the bright limb. There is a column headed “mm” to indicate the minimum aperture required for the event. Times are for Greenwich and in UT.

Lunar Graze Occultations

There are three possible graze occultations that occur during the period in question, the second of which could be very difficult due to the proximity of the terminator, despite the star being comparatively bright.

Eclipses

There will be a penumbral eclipse of the Moon on October 18/19. The Earth enters the shadow at 21.51 UT and leaves the following morning at 01.50 UT with maximum immersion of 66% occurring at 23.51 UT. To the seasoned observer it may be apparent that the southern limb is darker, but a casual glance from members of the general public will reveal nothing untoward.

|

Date |

Time |

Star |

Mag |

% illum |

N or S limit |

Cusp angle |

Limb |

|

Oct 11 |

19.50 |

HIP 94062 |

7.0 |

48 |

S |

7.5° |

dark |

|

Oct 23 |

03.12 |

104 Tauri |

4.9 |

-83 |

S |

0.1 |

terminator |

|

Nov 24 |

01.40 |

60 Cancri |

5.4 |

-66 |

N |

1.7 |

dark |

Far more unusual is the eclipse of the Sun that takes place on November 3, and although sadly there is no portion of it visible from the UK, parts of southern Europe will see a small partial. The event is unusual because at the time the Sun and Moon appear to be almost exactly the same size in the sky or in other words the umbral shadow only just touches the Earth’s surface. In such cases the curve of the Earth is enough to make the shadow fall short so that the Moon, instead of blotting out the Sun entirely, leaves a small annulus of sunlight remaining. The track of central eclipse begins in the Atlantic and only makes landfall once it has reached the African coast of Gabon. It then passes over The Republic of Congo, The Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda before concluding close to the Ethiopia/Somali border. Greatest eclipse occurs at 12.46 UT when totality will last for just one minute and forty seconds.

Comet 2012 S1 (ISON)

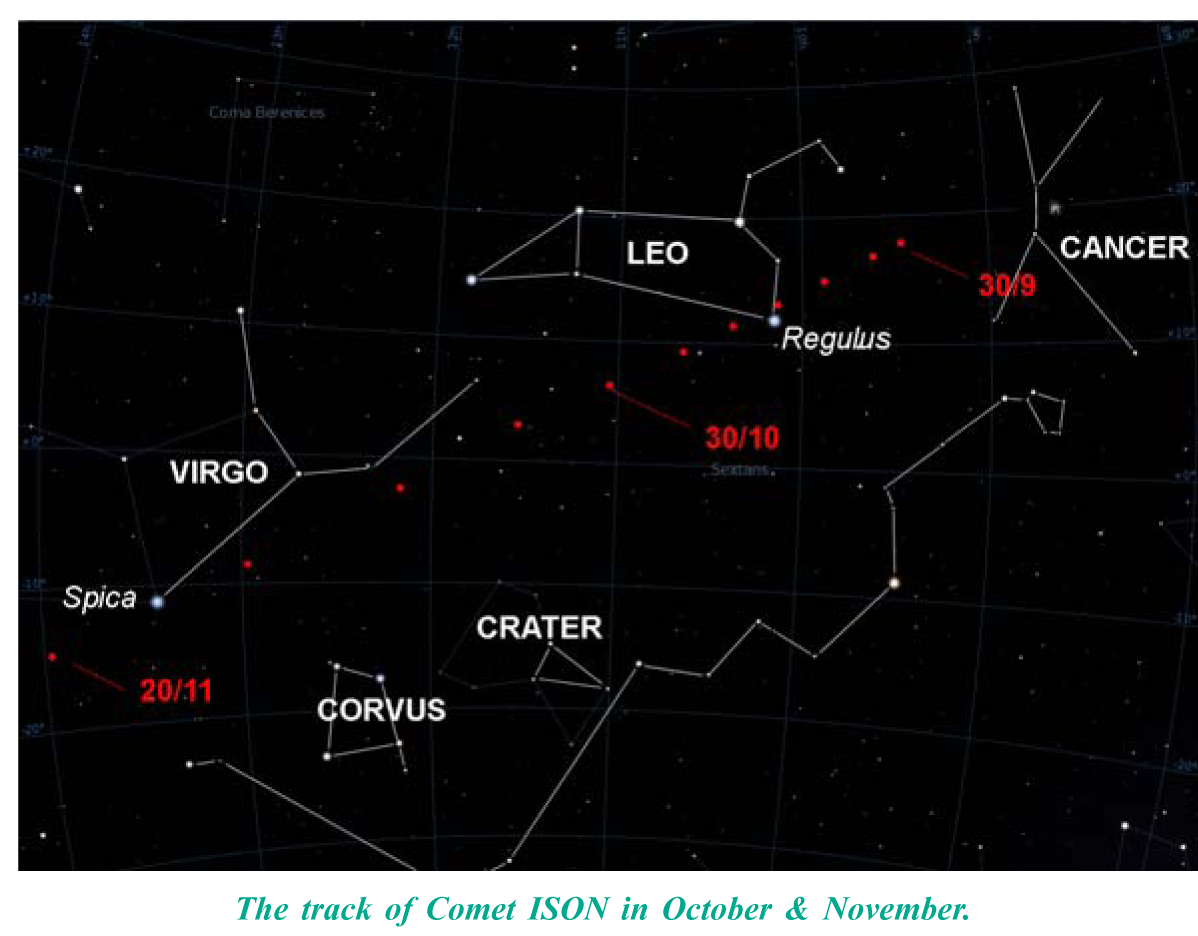

The map shows the position of comet ISON at five day intervals during the period of visibility before it reaches perihelion. Of course magnitude predictions are difficult and uncertain at the best of times, but it looks as if it may not live up to its earlier hype. The BAA Comet section has the ephemeris for this and other comets on its website at http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~jds/

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |