2017 May 25

Observer’s Challenge: The Sun at solar minimum

The conveyor belts of plasma deep inside the Sun drive the solar cycle and these have been slowing down almost to a grinding halt. This has led to speculation that we may be on the verge of another grand minimum like the Maunder Minimum that occurred between 1645 – 1715 when very few sunspots were seen at all. Of course we didn’t have the instruments and knowledge that we have today in those times and no one knows what the signs were just prior to the Maunder Minimum.

So will it be another such event or just another deep minimum like the one we experienced in 2008/09? This is why amateur observations day to day are so important, logging the activity seen (or not seen!); sending in those observations to the BAA Solar Section so that accurate records can be kept of the Sun’s activity cycle.

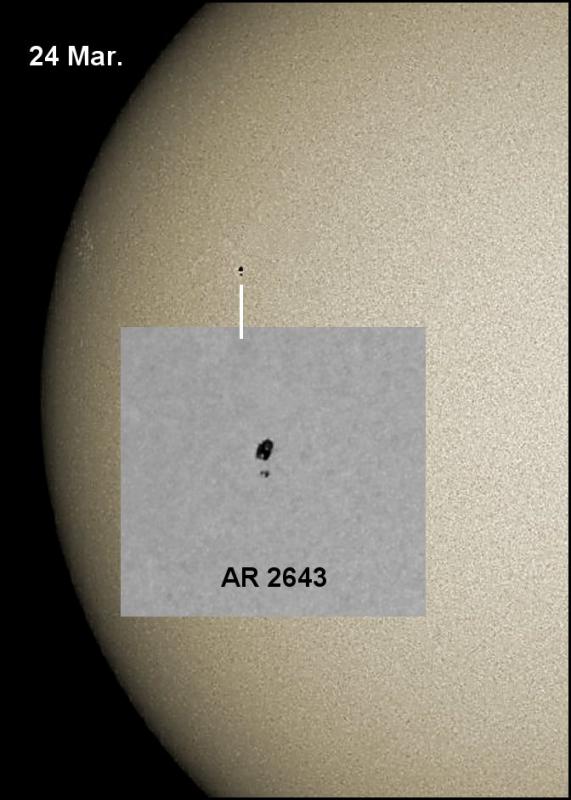

This in itself presents an observing challenge as large sunspot groups are easy to see. Sometimes just a single sunspot, or umbra without any penumbra, will cross the disk (“A” type group) which takes quite a bit of seeing against the solar glare (even through a solar filter and especially by the solar projection method).

Sometimes, two or three of these tiny sunspots travel in a close group together (“B” type group), also an observing challenge although maybe a little easier to see than an A type group.

Your observing challenge is to search the solar disk on a daily basis and to count any A and B type groups that you can see during June and to make a drawing. Draw a circle on a piece of white paper with a protractor (6” or 150 mm in diameter) and draw in your observation.

If you let the Sun’s disk drift through your eyepiece, the western limb will be the first to exit which will give you an idea of the Sun’s orientation. You can also check out activity on the Sun on a daily basis (which is correctly orientated) at the SOHO website

https://sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov/data/realtime-images.html

That is your second observing challenge. Mark in any faculae with a yellow pencil or a dotted pencil line to distinguish the feature from any sunspots. Try to follow any faculae from the eastern limb across the disk to the west (this will be harder as the feature reaches the brighter central regions of the Sun) and keep an eye out for any emerging tiny sunspot(s).

Remember never to look at the Sun with the unprotected naked eye. Always use a good solar filter or use the projection method. Full details can be found on the BAA Solar Section web pages or contact the Director for advice.

Lyn Smith, Director of the BAA’s Solar Section

If you have any solar observations (images, sketches, text reports etc) please do submit them to Lyn at the Solar Section and also upload them to your BAA Member Page. More observations of the Sun can be found on the BAA Members Pages.

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |