2017 December 10

Patterns in the sky

This article will discuss how the stars are divided up into constellations and how they are named.

The constellations

The human eye-brain combination is good at seeing patterns and joining up the dots. Millennia ago our ancestors did just this, forming what we now call constellations (Figure 1). Different civilisations around the globe created their own patterns in the sky to reflect local myths and legends.

The constellations that we now recognise are generally believed to have had their earliest origins in Mesopotamia (approximately modern day Iraq) around 3200BC with more and more added up to roughly 500BC.

Some constellations may have had an even earlier genesis. For example Ursa Major, the Great Bear, is recognised as such by many different cultures around the northern hemisphere even though it does not really resemble a bear; this leads us to wonder why so many seemingly un-related cultures hold such a similar belief. The suggestion is that as humans moved across the northern hemisphere they were sharing their ideas and beliefs, including the concept that this particular collection of stars represented a great bear in the night sky.

Starting in Eurasia, as people moved eastward they carried the tradition with them. During the ice age when sea levels were lower they crossed the Bering Straits and into North America where the bear is recognised as such by something like fifty percent of the Native American tribes. The implication of this is that the origins of the Great Bear go back at least 14,000 years to the last ice age. Even earlier than that, there are suggestions that markings in the famous Upper Paleolithic cave paintings of Lascaux in France show parts of the night sky.

However they originated, the constellations visible from the classical world came down to us from Mesopotamia via ancient Greece. There seems to have been a major influx of Mesopotamian constellations into Greece by 500BC. The Greeks adopted, added to and adapted these patterns to their own myths and heroes. In the second century AD the Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy, in a work that we now call The Almagest, compiled a list of 48 constellations that forms the basis of what we use today.

These constellations reflect the myths of the ancient world showcasing its heroes and monsters. There is Orion the mighty hunter, the legendary Hercules and many more. Some of these are woven from complete stories. We have Andromeda the daughter of king Cepheus and queen Cassiopeia. Chained to a rock as a sacrifice to the sea monster Cetus, she is rescued by Perseus arriving, in some versions of the myth, on the winged steed Pegasus. All of these characters are now constellations in the sky.

The stars of the southern skies had to wait until the voyages of discovery from the 15th century onwards to be charted by Europeans though many of the peoples of the southern hemisphere would have had their own constellations long before this. Many of the new constellations formed in the southern sky, rather than representing myths and legends from the ancient world, reflect the discoveries and ideas of the age, so we find a telescope, a microscope and a number of exotic birds amongst others.

As time went by more and more constellations were added with almost every new map of the sky. This was not just with the southern stars but new constellations were also carved from existing ones. Eventually the system became chaotic and unwieldy; time was ripe for order to be brought forth from chaos.

In the first part of the twentieth century the newly formed International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally defined the eighty-eight constellations marking down their boundaries in the sky and establishing the global standard we use today. The IAU continues to be the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations related to celestial bodies.

Below is a list of the eighty-eight constellations which are formally recognised today. The official names are in Latin and these are what are generally used. Beside them I have provided an English translation and the standard abbreviation. The last column is the Latin ‘genitive form’ of which more later.

| Latin name | English translation | Abbr. | Genitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andromeda | The chained maiden | And | Andromedae |

| Antlia | Air pump | Ant | Antliae |

| Apus | Bird of paradise | Aps | Apodis |

| Aquarius | Water bearer | Aqr | Aquarii |

| Aquila | Eagle | Aql | Aquilae |

| Ara | Altar | Ara | Arae |

| Aries | Ram | Ari | Arietis |

| Auriga | Charioteer | Aur | Aurigae |

| Boötes | Herdsman | Boo | Boötis |

| Caelum | Engraving tool | Cae | Caeli |

| Camelopardalis | Giraffe | Cam | Camelopardalis |

| Cancer | Crab | Cnc | Cancri |

| Canes Venatici | Hunting dogs | CVn | Canum Venaticorum |

| Canis Major | Great dog | Cma | Canis Majoris |

| Canis Minor | Lesser dog | Cmi | Canis Minoris |

| Capricornus | Sea goat | Cap | Capricorni |

| Carina | Keel | Car | Carinae |

| Cassiopeia | The Seated queen | Cas | Cassiopeiae |

| Centaurus | Centaur | Cen | Centauri |

| Cepheus | The King | Cep | Cephei |

| Cetus | Sea monster | Cet | Ceti |

| Chamaeleon | Chameleon | Cha | Chamaeleontis |

| Circinus | Compass | Cir | Circini |

| Columba | Dove | Col | Columbae |

| Coma Berenices | Berenice’s hair | Com | Comae Berenices |

| Corona Australis | Southern crown | CrA | Coronae Australis |

| Corona Borealis | Northern crown | CrB | Coronae Borealis |

| Corvus | Crow | Crv | Corvi |

| Crater | Cup | Crt | Crateris |

| Crux | Southern cross | Cru | Crucis |

| Cygnus | Swan | Cyg | Cygni |

| Delphinus | Dolphin | Del | Delphini |

| Dorado | Swordfish | Dor | Doradus |

| Draco | Dragon | Dra | Draconis |

| Equuleus | Little horse | Equ | Equulei |

| Eridanus | River Eridanus | Eri | Eridani |

| Fornax | Furnace | For | Fornacis |

| Gemini | Twins | Gem | Geminorum |

| Grus | Crane | Gru | Gruis |

| Hercules | Hercules | Her | Herculis |

| Horologium | Clock | Hor | Horologii |

| Hydra | Female water Snake | Hya | Hydrae |

| Hydrus | Male water snake | Hyi | Hydri |

| Indus | Indian | Ind | Indi |

| Lacerta | Lizard | Lac | Lacertae |

| Leo | Lion | Leo | Leonis |

| Leo Minor | Lesser lion | Lmi | Leonis Minoris |

| Lepus | Hare | Lep | Leporis |

| Libra | Scales | Lib | Librae |

| Lupus | Wolf | Lup | Lupi |

| Lynx | Lynx | Lyn | Lyncis |

| Lyra | Lyre | Lyr | Lyrae |

| Mensa | Table Mountain | Men | Mensae |

| Microscopium | Microscope | Mic | Microscopii |

| Monoceros | Unicorn | Mon | Monocerotis |

| Musca | Fly | Mus | Muscae |

| Norma | Carpenter’s square | Nor | Normae |

| Octans | Octant | Oct | Octantis |

| Ophiuchus | Serpent bearer | Oph | Ophiuchi |

| Orion | The hunter | Ori | Orionis |

| Pavo | Peacock | Pav | Pavonis |

| Pegasus | The winged horse | Peg | Pegasi |

| Perseus | The hero | Per | Persei |

| Phoenix | Phoenix | Phe | Phoenicis |

| Pictor | Painter’s easel | Pic | Pictoris |

| Pisces | Fishes | Psc | Piscium |

| Piscis Austrinus | Southern fish | PsA | Piscis Austrini |

| Puppis | Stern (of a ship) | Pup | Puppis |

| Pyxis | Compass | Pyx | Pyxidis |

| Reticulum | Reticle | Ret | Reticuli |

| Sagitta | Arrow | Sge | Sagittae |

| Sagittarius | Archer | Sgr | Sagittarii |

| Scorpius | Scorpion | Sco | Scorpii |

| Sculptor | Sculptor | Scl | Sculptoris |

| Scutum | Shield | Sct | Scuti |

| Serpens | Serpent | Ser | Serpentis |

| Sextans | Sextant | Sex | Sextantis |

| Taurus | Bull | Tau | Tauri |

| Telescopium | Telescope | Tel | Telescopii |

| Triangulum | Triangle | Tri | Trianguli |

| Triangulum Australe | Southern triangle | TrA | Trianguli Australis |

| Tucana | Toucan | Tuc | Tucanae |

| Ursa Major | Great bear | Uma | Ursae Majoris |

| Ursa Minor | Little Bear | Umi | Ursae Minoris |

| Vela | Sails | Vel | Velorum |

| Virgo | Virgin | Vir | Virginis |

| Volans | Flying fish | Vol | Volantis |

| Vulpecula | Fox | Vul | Vulpeculae |

It is worth noting a few facts about some of these constellations and their names:

- As noted above, you should generally use the Latin names when referring to constellations. However some English versions have entered common usage such as the Great Bear and Southern Cross although these are very much the exception.

- The English translations in the above list are from the official IAU website. Several of the constellations represent named mythological characters and these are usually referred to by their Latin name, not the translation. For example Andromeda is invariably referred to as Andromeda, if you call her the chained maiden you will likely get some strange looks. The same applies to Cassiopeia, Cepheus, Hercules, Orion, Pegasus and Perseus.

- Apus: This is sometimes rendered in English as The Bee. This is incorrect, the error is believed to have been caused, at some point, by a misspelling or translation error since the Latin for bee is Apis.

- Carina, Puppis and Vela were once the parts of a much larger constellation, Argo Navis, the ship Argo. This was one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations but because of its enormous size it was split into these three separate constellations.

- Cetus: This is often translated as the whale rather than sea monster.

- Reticulum: A reticle is a set of wires or cross hairs in a telescope eyepiece used for measurement purposes.

- Serpens: Unlike all the other constellations, Serpens is split into two entirely separate parts, one on either side of Ophiuchus the Serpent Bearer. The westernmost part is referred to as Serpens Caput (the serpent’s head) and the easternmost, Serpens Cauda (the serpent’s tail).

Asterisms

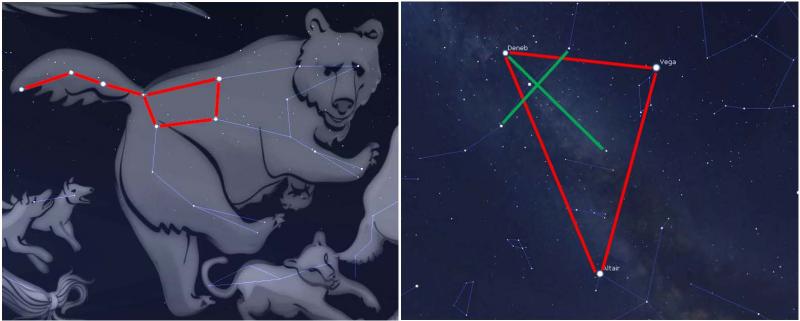

In addition to constellations there are also more informal patterns known as asterisms. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Plough or Big Dipper. Many people think of this as a constellation in its own right. In reality it is only part of the larger constellation of Ursa Major (Figure 2A).

Some asterisms are formed from parts of several constellations rather than just one. For example the so-called Summer Triangle is formed from the brightest stars of Cygnus, Lyra and Aquila. Cygnus itself contains the well-known asterism, The Northern Cross (Figure 2B).

Joining the dots

For many centuries the constellations were viewed as pictures of the objects they represented as shown in Figure 3A. Many of the early star atlases and globes were things of great artistic beauty but they did not make it easy to translate the pictures into the star patterns in the sky.

Nowadays we create simple stick figures by joining up the brightest stars as in Figure 3B. You may be wondering if there are standard, official representations for these patterns. The answer is no, there are many variations.

In 1952 an American author, H. A. Rey, wrote a book entitled “The Stars: A New Way to See Them”. In this he redrew the star patterns so that they were more representative of what the constellations were meant to represent. These layouts, sometimes called ‘modern layouts’ are quite popular but there are a couple of issues. Firstly, Rey often used faint stars to create his patterns. In today’s light polluted skies these may well not be visible. Secondly, he sometimes goes against the classical representations, for example what is traditionally shown as the head of Cetus the whale or sea monster Rey depicts as its tail.

Naming names

So far we have grouped the stars into constellations but how do we then identify individual stars? Some of the brighter stars have names to identify them so we have Sirius, Rigel, Vega, Deneb, Polaris and so on. However with around three thousand stars visible at any one time in a dark sky this method soon ceases to be practical.

A better way is to identify a star within its parent constellation. This has been done in a number of ways over the centuries. The German astronomer Johann Bayer who in 1603 published a new star atlas entitled Uranometria first defined the method in use today. To each plotted star he assigned a lower case Greek letter, with alpha being usually, but not always, the brightest star in the constellation, beta the second brightest and so on. He suffixed this with the genitive version of the constellation. So Sirius is Alpha Canis Majoris.

The genitive version is the ‘of’ or possessive form of the name. Alpha Canis Majoris means the alpha star of Canis Major and would normally be abbreviated Alpha CMa. Where there were so many stars in a constellation that the Greek letters ran out he carried on by using the letters of the normal alphabet we use every day. Bear in mind that Bayer’s star atlas was published before the invention of the telescope so he did not have to worry about faint stars below the naked eye limit.

Successive catalogues have added to this scheme, for example by assigning a number to each star. There are special schemes for stars that vary in brightness and so on. Generally speaking for the naked eye Bayer’s scheme is all that is needed.

Below is a table of the lower case Greek alphabet.

| Alpha | α | Iota | ι | Rho | ρ |

| Beta | β | Kappa | κ | Sigma | σ |

| Gamma | γ | Lambda | λ | Tau | τ |

| Delta | δ | Mu | μ | Upsilon | υ |

| Epsilon | ε | Nu | ν | Phi | φ |

| Zeta | ζ | Xi | ξ | Chi | χ |

| Eta | η | Omicron | ο | Psi | ψ |

| Theta | θ | Pi | π | Omega | ω |

Do you need to learn the Greek alphabet? The answer is it depends on what you want to do with your astronomy. Generally when reading articles about the stars an object will have the Greek character spelt out alongside the actual letter itself. An example would be alpha (α) CMa or α (alpha) CMa. Where it is really useful is in reading star charts, here you will only find the Greek character; quite simply there is often no room for both that and the full spelling. My advice would be to try it and see how you get on; you may find that you pick up the symbols through practice and regular use without having to formally learn them.

In conclusion

The sky we look out upon today can seem very different from that seen by our ancestors when they created the first constellations. Whereas they had clear pristine skies, we are plagued in many areas of the world by man made light pollution. This robs us of the night sky and can often obliterate many of the fainter stars that make up the constellations. The BAA is in the forefront of the fight against unnecessary lighting and you can read about the problems and solutions here.

A future article will discuss how to discover which constellations are visible at any particular time and how to find your way around them.

In the meantime, whatever your skies, go out at night, look up and enjoy what there is to see. Contemplate that in doing so you are reaching out into the depths of space and that the light entering your eyes has been travelling tens, hundreds and in some cases thousands of years to reach you and impact on your retinas.

To return to Starting out in Astronomy page. Select Here

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |