Sky notes for 2025 December & 2026 January

2025 December 1

With the Winter Solstice on Dec 21, the long nights return. These extended hours of darkness allow observing sessions that start in the early evening and end only when the cold or dew finally become intolerable. If a long deep-sky session is planned, it makes sense to begin in the deep south, where the quarry is visible for the shortest time. As autumn’s water-themed constellations slip into the southwest and winter’s glitter becomes more prominent, one ‘liquid’ constellation remains apparent – or at least half of it does: Eridanus, the River. After this, we sweep upward through Fornax before turning north to explore the rich skies around Taurus, Cassiopeia and Perseus – a deep-sky tour for the long nights ahead.

The deep sky

Eridanus, the celestial river, meanders in leisurely fashion towards the southern horizon before cascading steeply to splash into the deep south at Achernar, first magnitude alpha Eridani. Although it is the ninth brightest star in the heavens, Achernar is not accessible to northern-hemisphere observers. The river’s spring rises just west of brilliant Rigel, the south-western star of Orion. Thereafter, it flows west to the eastern border of Cetus at eta Eridani, before sweeping south and then back east in the stream of nine stars that comprise tau Eridani. From just above the UK horizon, the river continues its journey south-west to meet Achernar at −57° south.

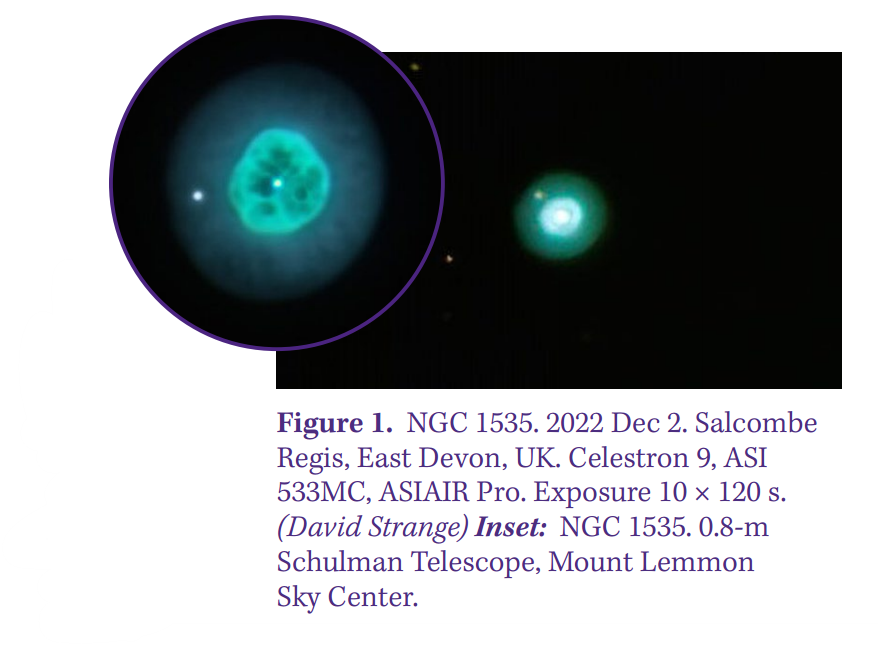

For northern observers, Eridanus’ main deep-sky delights are the Witch’s Head Nebula (IC 2118) and the small, bright planetary nebula NGC 1535 (Figure 1). The latter is a colourful 9.1-magnitude oval, some 48 × 42 arcsec, discovered by William Herschel in 1784. Its high surface brightness takes magnification well; the green nebula is of similar apparent dimensions to Jupiter, although clearly very much fainter. Was it this that caused Herschel to develop the ‘planetary nebula’ class of deep-sky object? The bright inner disc is easily seen, but the faint outer fringe is much more challenging, requiring great transparency and patience. The central star is magnitude 11.6, and the nebula is rated highly by many observers.

Most other deep-sky objects in Eridanus are galaxies – mainly unimpressive examples, but one is a stunner. NGC 1300 (top of page 430) is a beautiful barred spiral of magnitude 10.4 and, although quite small (5.5 × 3 arcmin), it is accessible as it lies only 19° south. It is 70 million light-years away and quite a large galaxy some 150,000 light-years across, seen 43° from edge-on.

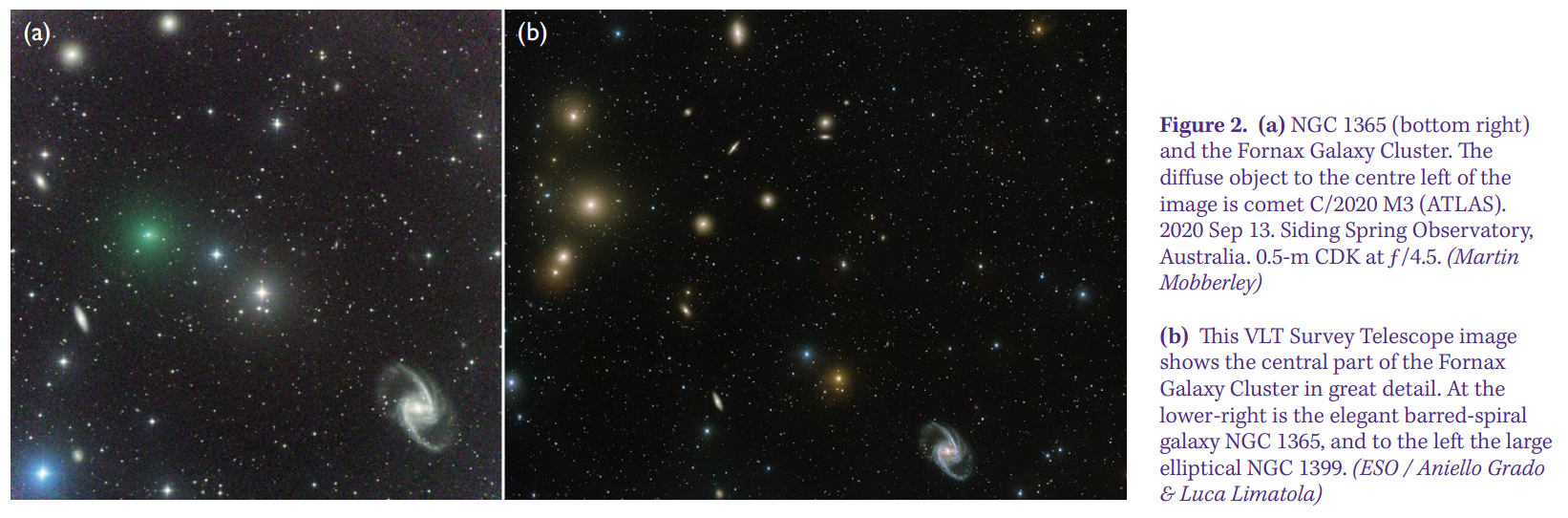

Even further south – and hence difficult for British observers – lies Fornax, the Furnace. Another fabulous barred spiral resides here, but at −36° it is a very tricky target even from the south coast of England. It is worth travelling to more southerly latitudes, or using remote telescopes, to capture it. NGC 1365 (Figures 2a & 2b, page 430) must be the most stunning barred spiral of them all. With an estimated span of 160,000 light-years and containing some 200 billion stars, it is quite Milky Way-like, although with only two spiral arms compared with our galaxy’s four. Its apparent dimensions are 11.2 × 5.9 arcmin, and it lies 60 million light-years away. At magnitude 8.3, it would be an easy object were it not for its southerly declination.

Just east of this marvel, and overlapping with Eridanus, is the Fornax Galaxy Cluster (see again Figures 2a & 2b, page 430), the second-largest galaxy cluster within 100 million light-years, after the Virgo Cluster. It lies in almost the opposite direction from the Virgo hoard and contains at least 58 members, among them NGC 1365. NGC 1316 and NGC 1399 are bright lenticular and elliptical galaxies respectively.

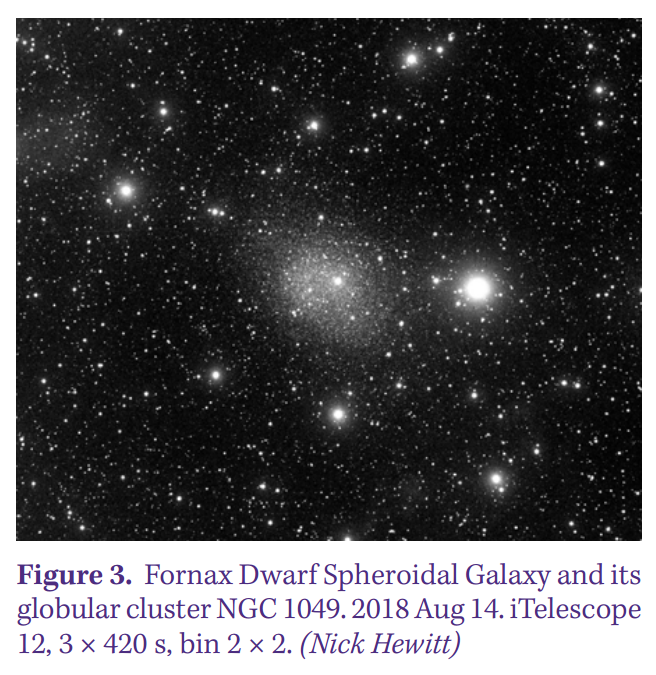

A companion of the Milky Way might just be glimpsed on the clearest nights, but at −34° it will never be easy. The Fornax Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy (Figure 3) is located just south-west of beta Fornacis and quite accessible from southern Europe, La Palma and through remote imaging. It has an extremely low surface brightness and was only discovered in 1938 by Harlow Shapley, yet it hosts an NGC globular cluster, NGC 1049, which is gravitationally bound to it and was discovered by William Herschel – so it must be visible from Slough, at least! The globular too is a challenge at 12th magnitude and of small angular size, but it may be glimpsed visually in larger reflectors. There are five additional globulars (Fornax 1–6) in the dwarf’s halo, although these are likely to be beyond detection by most. The Fornax Dwarf lies some 450,000 light-years from us. Do not be fooled by its listed magnitude (9.3): its glow is spread thinly over 17 × 13 arcmin, so – as with most dwarf galaxies – it is best seen through imaging.

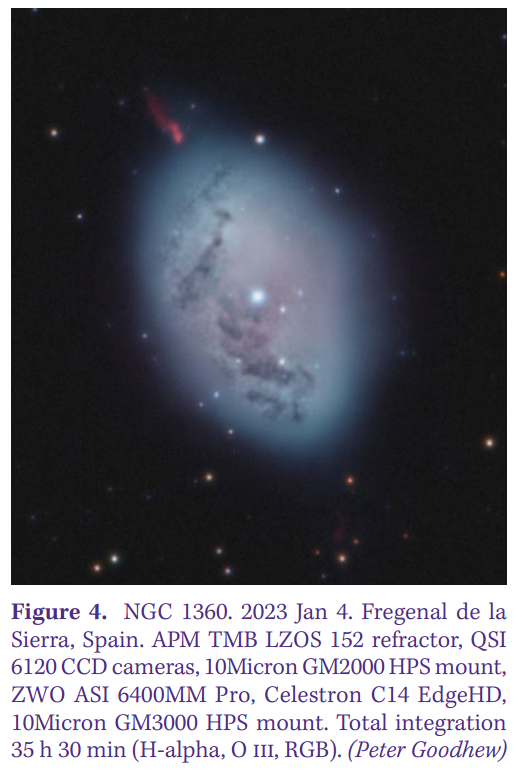

If the Fornax galaxies are beyond your possibilities, a much easier but rarely visited planetary nebula on the Eridanus-Fornax border may restore your faith. NGC 1360 (Figure 4) is higher (−25°) and bright at 9th magnitude, and quite large at 9 × 5 arcmin. Its central star is quite prominent. Sharing the same declination as Antares, the nebula is often overlooked, but can be located near two 6th-magnitude stars and the red semiregular variable RZ Fornacis, which varies between magnitude 9.1 and 10. Using high power on this ‘Robin’s Egg’ planetary is rewarding.

These low-declination targets are always difficult from Britain and become almost impossible from further north than Edinburgh, or they become buried in the mists and murk of winter. Let us venture further north of the celestial equator, where more accessible deep-sky joys are arrayed. Taurus is on the meridian at 9 pm with its assorted clusters and nebulae, and we can still enjoy the brilliant clusters of vain Cassiopeia and heroic Perseus with his gory handful, both still well placed high in the north-west.

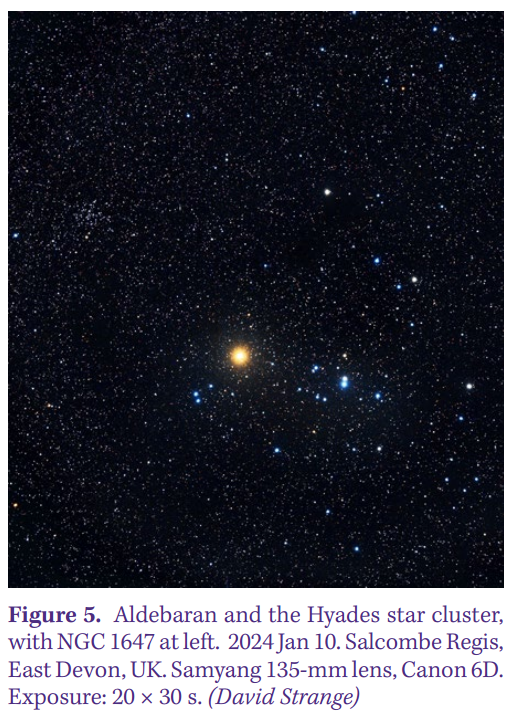

Taurus is a delight, with its famous and historically important star clusters, the Hyades (Figure 5) and the Pleiades (or Seven Sisters) dominating. The Hyades is a large cluster in apparent size due to its relative proximity at 153 light-years. It has been studied in depth and is a cornerstone of the cosmic distance ladder. First-magnitude, deep-orange Aldebaran (Figure 5), the 14th-brightest star in the sky, is unrelated being just 67 light-years away. The Pleiades never fails to impress, being easy with the naked eye, gorgeous in binoculars and stunning in wide-field telescopes. At 440 light-years, it is the next rung on the distance ladder and fully studied.

Other clusters are less often observed, perhaps being overshadowed by the Pleiades’ glamour. Two easy examples lie within the ‘horns’ of the Bull: NGC 1647 (Figure 5) and NGC 1746. NGC 1647 – a bright cluster of magnitude 6 – is nestled near where the horns originate at the bull’s head. Larger than the full Moon at 40 arcmin across, it is 1,700 light-years distant, so 11 times further than the Hyades. William Herschel recorded it in 1784, and it is straightforward in binoculars. If a telescope is used, low power is best. A similar cluster, NGC 1746, can be found further east, below the northern horn towards Elnath (beta Tauri or gamma Aurigae – it is claimed by both constellations). It is again around 6th magnitude but larger and sparser than NGC 1647, so a little less prominent. There has been some confusion over the cluster, as it may well be two small, conjoined clusters (NGC 1750 and NGC 1758), causing historical controversy.

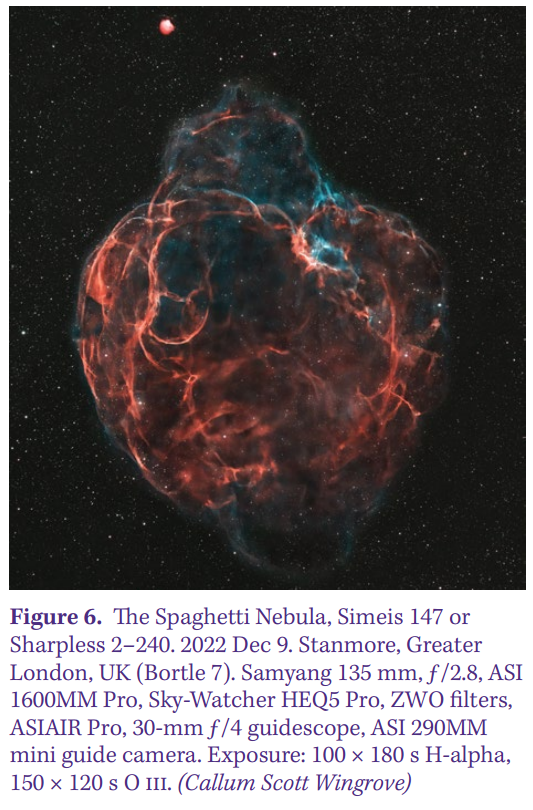

The best-known supernova remnant lies near zeta Tauri, near the tip of the southern horn. The Crab Nebula (NGC 1952) is the remnant of the Type ii supernova first recorded in 1054 AD. It is quite bright and much imaged, with narrowband filters picking out the hydrogen filaments against the milky background, and the residual pulsar visible too. Another much more challenging supernova remnant on the Taurus-Auriga border is Simeis 147 (Figure 6), now known as the Spaghetti Nebula. Although the brighter patches have been glimpsed visually, it has become a favourite of narrowband imagers as it is so large and complex. Only discovered in the 1950s, it may be 40,000 years old and span 160 light-years.

The solar system

Moon & Sun

The Sun is at its lowest declination and thus has its shortest appearance of the year as the winter solstice falls on Dec 21. However, it remains an active star and could still produce interesting phenomena such as sunspots, prominences and possibly auroral displays. Keep watching!

There are no eclipses during December or January.

Planets

Mercury flies the flag for the terrestrial planets over Christmas and the New Year. It is at greatest western elongation on Dec 17, delivering good morning viewing opportunities in mid-December before disappearing into superior conjunction on Jan 21.

Venus is at superior conjunction on Jan 6 and Mars is at superior conjunction on Jan 9, so neither is observable.

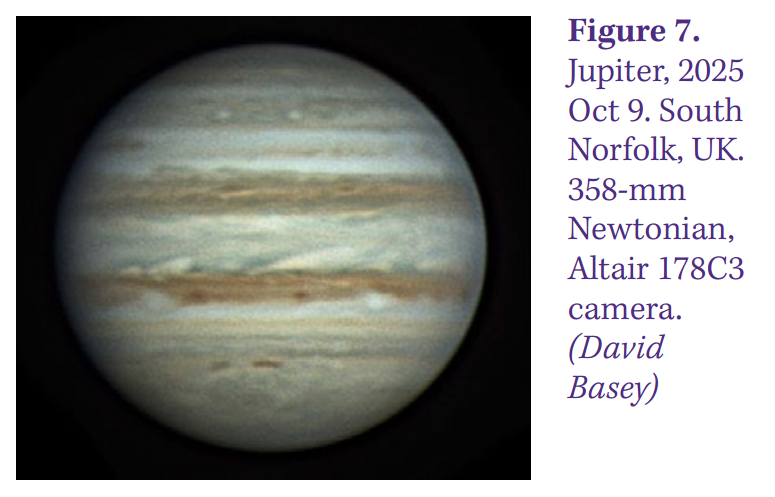

The gas giants compensate for the absence of inner planets. Jupiter (Figure 7) is spectacular in Gemini at magnitude −2.6, dominating the sky. Positioned so high, Earth’s atmosphere is much less of a hinderance than usual, and the planet can be observed all night if so desired. In addition to the ongoing delight of observing changes in its belts and spots, transits by the Galilean moons occur – Europa on Jan 11 and Io on Jan 29. Jupiter lies near the Eskimo Nebula (NGC 2392) when at opposition on Jan 10.

Saturn remains available for evening scrutiny, the rings remaining narrow to our view but opening to +4° by the end of January. Early evening in the first half of January offers the best views, with Titan transiting on Jan 9.

Uranus, just past its November opposition, remains very well placed in Taurus, south-east of the Pleiades. Easy enough to locate at magnitude 5.6, little can be imaged on its 3.7-arcmin disc, although the dance of its brightest moons is always a delight.

Neptune remains available to observe in the early evening, at magnitude 7.7 and lying north-east of Saturn. It shows a 2.3-arcmin blue-green disc.

(1) Ceres is well placed in Cetus at magnitude 9 and (2) Pallas can be glimpsed at magnitude 10.5 in Aquarius in the early evening.

Meteors

The best meteor shower of the year is the Geminids, peaking on Dec 13–14. The radiant lies near Castor, and this year the waning crescent Moon will not interfere until around 3 am. The Geminids can be the richest shower of the year and rarely disappoint, so thanks are due to asteroid 3200 Phaethon for providing the debris.

The first shower of every new year is the Quadrantids on Jan 3–4. Unfortunately, this normally fine display is ruined by the full Moon on Jan 3, the night of maximum activity.

Comets

By December, the best autumnal comet, C/2025 A6 Lemmon, is too close to the Sun for observation. However, periodic comet 24P/Schaumasse reaches perihelion on Jan 8 and is a morning object, lying between Boötes and Virgo. It may peak at magnitude 8, making it accessible to small telescopes throughout the month. With a period of eight years, observations have been hit-and-miss over the years, it being unfavourably placed in 1968, 1976 and 2009, although it reached magnitude 10 in 2017. This apparition should be better.

C/2025 R2 SWAN is an evening comet but is fading rapidly as it traverses Pisces, becoming difficult to observe by the turn of the year.

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |