Beyond the Beehive

2023 February 7

The constellation Cancer is another rather faint and indistinct constellation, with no really bright stars. It has one landmark deep-sky object, the open cluster Messier 44, but looking deeper there are many further targets to entice and entertain.

First, a few words about Messier 44 – historically known as Praesepe (the manger), but also commonly known as the Beehive. I am not sure who coined the name ‘Beehive’, though Smyth uses both names in his observation of 1831. M44 is one of the finest open clusters to view in the northern hemisphere. Galileo resolved about 40 stars, but professional observations suggest there are about 200 in the cluster; there are 350 or more in the area. Some estimates place the number much higher.

Measurements put the cluster at about 182 parsecs from us, making it one of the closest. Proper motions of the stars suggest it is moving in the same direction as the Hyades cluster, indicating a common origin. At about 600 million years old, it formed when on Earth the first multi-celled organisms started to appear (the Ediacaran Period). Two bright stars are near the cluster; Asellus Borealis (gamma Cancrii) and Asellus Australis (delta Cancrii) are the northern and southern donkeys, which are said to be eating at the manger. Delta Cancrii also goes by the magnificent name Arkushanangarushashutu (the longest star name).

Lying about eight degrees south-south-west of the Beehive is the only other Messier object in Cancer: another open cluster, M67. It is interesting to compare and contrast the two clusters. Whilst M44 is very young, M67 is very old, at about four billion years old. This is almost as old as our solar system. Old open clusters are rare because the stars tend to disperse into the general melee of the spiral arms. But M67 seems to be relatively intact, with over 500 members. Most are well-evolved stars – red giants and white dwarfs – but a number are ‘blue stragglers’: blue stars that have been created by collision or other processes.

And while on the subject of stars, Cancer is home to one of the reddest: X Cancrii. It lies a short distance west of delta Cancrii, and should be easy to spot. (Do not confuse with chi (χ) Cancrii.) A variable star, it varies in brightness over 193 days from around magnitude 5.5 to 7.50 – at the time of writing (2022 December) it is reported as mag 7.4 (AAVSO), so it should be brighter in February/March.

Two difficult planetaries

Most other deep-sky targets in Cancer are somewhat more challenging. There are two planetary nebulae worth trying for, Abell 30 and 31, but both are pretty faint.

Abell 30 lies close to delta Cancrii, which would be a good jumping-off point. At only about two arcminutes across and magnitude 13, detection will be a challenge for the visual observer, but with a large scope and an OIII or UHC filter you might have success. Abell 30 is an unusual planetary, being one of the ‘born again’ class that seems to have undergone a secondary phase of development. It is also likely to have a binary central star.

Abell 31 is in the southern part of the constellation. It is brighter than Abell 30, at magnitude 12, but also much larger – about 16 arcminutes across, so surface brightness is pretty low. Again, a possible visual target for users of large telescopes.

Some challenging galaxies

Cancer might not be the first place you think about when planning a galaxy-hunting session, but there are lots of interesting examples to seek out.

At the western side, look for the nice pairing of NGC 2562 and 2563, which accompany a number of other galaxies in a field of a degree or so. To the north-west of delta Cancrii, look out for the close pair NGC 2672 and 2673, which are catalogued in Halton Arp’s Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies as Arp 167. You might need some high magnification and a large telescope to split the two, as NGC 2672 tends to rather swamp 2673.

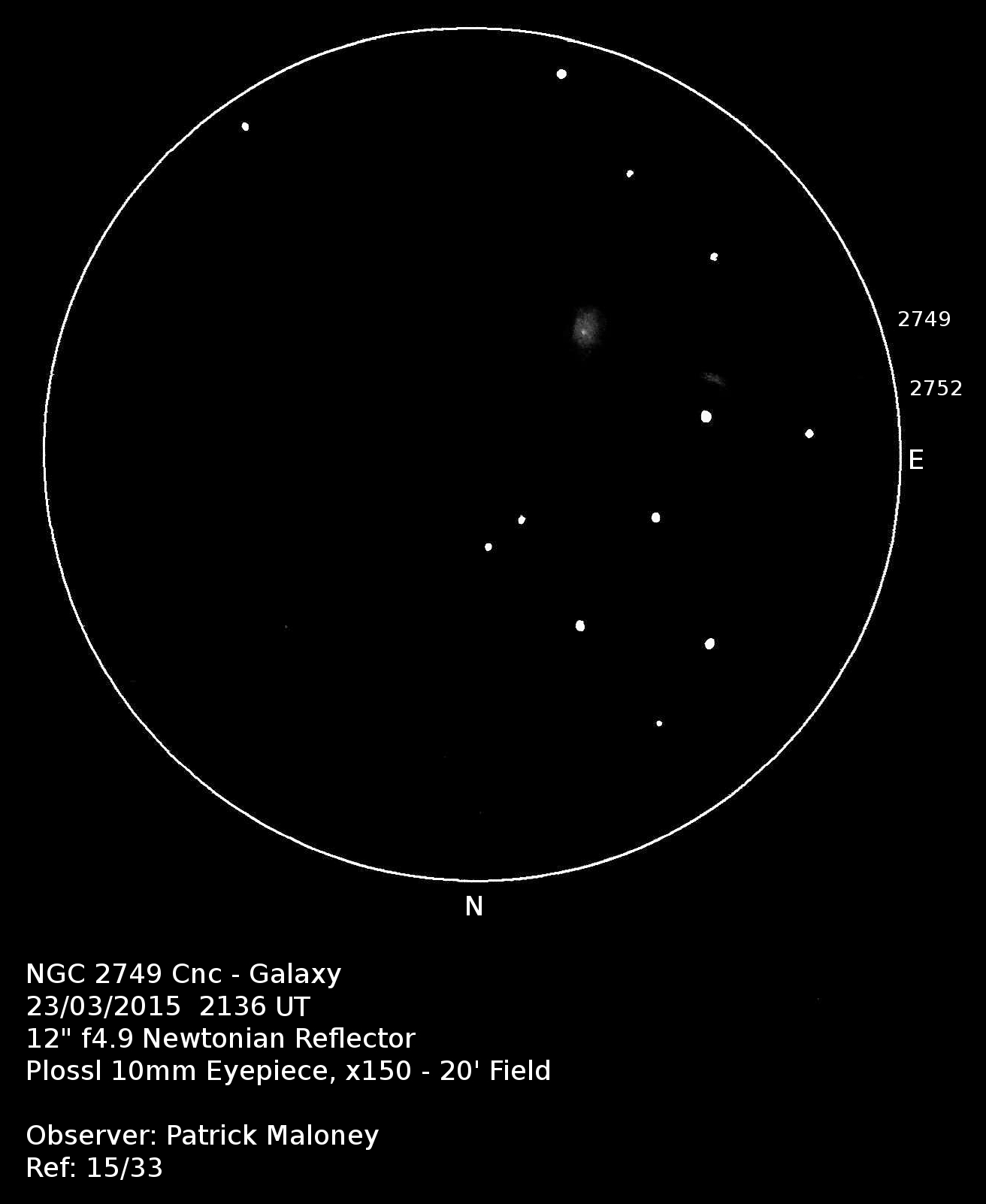

At the eastern side, NGC 2749 is one of the brighter galaxies in the area. Also check out NGC 2795 and 2797, which sit in another fascinating grouping of galaxies.

And finally, to return to my ‘beyond the Beehive’ theme, there are a couple of background galaxies that can be seen behind M44: NGC 2624 on the western side of the cluster, and NGC 2647 on the eastern. If you have imaged M44 in the past and not realised these galaxies are there, why not check your pictures to see if you have picked them up?

I hope you have fun hunting down these targets in Cancer, and there are many more to find if you equip yourself with a good star atlas. If you have success observing any of these objects, please let me know, and post any images to your Member’s Album on the BAA website. Good luck!

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |