Death of a comet

2014 January 26

The much-hyped ‘comet of the century’ died on the day of perihelion passage and its remains are scattered throughout the Solar System. It will be much missed by comet observers and those keen on hyperbole.

The much-hyped ‘comet of the century’ died on the day of perihelion passage and its remains are scattered throughout the Solar System. It will be much missed by comet observers and those keen on hyperbole.

C/2012 S1 (ISON) was discovered by Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok on 2012 September 21 using a 0.4m, f/3 reflector at the International Scientific Optical Network Observatory, Kislovodsk, Russia. At the time the comet was around magnitude 18 and 6.4au from the Sun. Astrometry quickly showed that the comet would pass extremely close to the Sun (around 0.012au) on 2013 Nov 28.8.

Unfortunately, many people started to extrapolate the behaviour of the comet from its initial deep-frozen location to how it would look when baked by the Sun at perihelion. Since the available data were limited the consequent uncertainties were huge but media outlets are not known for their ability to handle probabilities. Five days after the discovery the Daily Telegraph told its readers to prepare for a comet ‘fifteen times brighter than the Moon’. Admittedly they didn’t specify the phase of the Moon, but the intention was clear. This comet would be spectacular.

Those of us who knew better advocated some caution. From the orbit it was clear that this was a ‘dynamically new’ comet. Such comets are new visitors to the inner Solar System and they tend to be unusually active far from the Sun but often disappoint when they come closer in. Despite that, many of us hoped that ISON would put on a good show. It was going to pass very close to the Sun and would be well positioned in the eastern morning sky from the UK if it survived. We all hoped for something similar to Terry Lovejoy’s comet two years ago (C/2011 W3) which had been a spectacular object post-perihelion even though it broke up. Unfortunately this ‘headless wonder’ comet had only been visible from the southern hemisphere so those of us in the north waited in anticipation of what ISON would do.

A lot depended on the size of the nucleus. By 2013 September there was worrying evidence that ISON’s was small (probably less than 1km) and that it might not survive perihelion. Even worse, by early November the magnitude of the comet was still well below even some of the more pessimistic predictions.

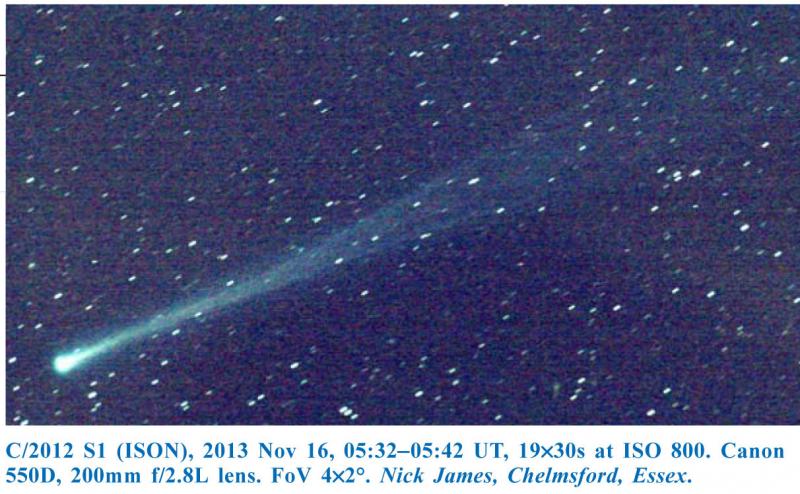

All that changed on Nov 11 when there appears to have been a significant outburst and, all of a sudden, this was a comet that was worth getting up to see. I photographed it with a long tail on Nov 16 when it was low in the east in Virgo, and the comet was easily visible in binoculars at that time. While it was spectacular this outburst was the first of a series which eventually led to the complete disintegration of the nucleus.

As the comet got closer to perihelion it became more and more difficult to see from the ground. Pete Lawrence obtained a fine image (front cover) from La Palma on Nov 22 whilst filming The Sky at Night. On the next day the crew of the ISS managed to photograph the comet using a hand-held camera and 1/10s exposure, but after that, the only views were from the solar monitoring spacecraft STEREO and SOHO.

As the comet got closer to perihelion it became more and more difficult to see from the ground. Pete Lawrence obtained a fine image (front cover) from La Palma on Nov 22 whilst filming The Sky at Night. On the next day the crew of the ISS managed to photograph the comet using a hand-held camera and 1/10s exposure, but after that, the only views were from the solar monitoring spacecraft STEREO and SOHO.

The comet brightened dramatically as it approached the Sun, reaching probably mag 2 early on the morning of perihelion day, but this was its last gasp as other observations indicated that the nucleus had completely disrupted and that dust and gas production had stopped. As the comet disappeared behind the coronagraph occulting disk it was clear that it was fading fast. By the time it re-emerged a few hours later all that was left was a rapidly expanding and fading cloud of dust. A sequence of SOHO images is shown in the inset on the front cover.

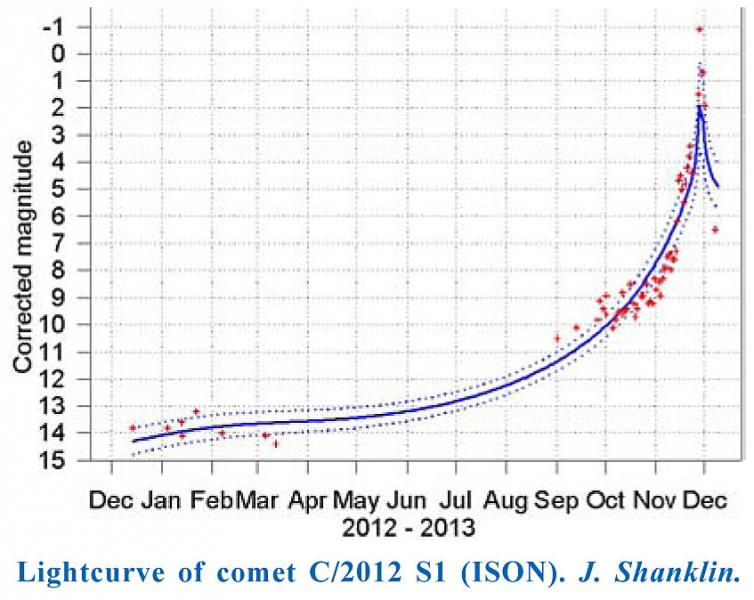

Comet Section Director Jonathan Shanklin provided the lightcurve given here. This shows daily mean magnitudes corrected for aperture and a curve based on m= 7.3 + 5 log + 5 log r. This curve does not capture the likely peak magnitude of 2.2 as the comet was this bright for much less than a day. From mid-December the position of the comet’s remains has been accessible in a dark sky from the Earth but despite a number of very deep searches, nothing convincing has been seen.

It’s a shame that ISON didn’t perform as we had hoped but watching the comet’s demise live on the Internet was fascinating. Hopefully, some people have learned the hard lesson that comets are highly unpredictable things. That is part of what makes them so interesting.

As compensation we have had an excellent comet in the morning sky. C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy) has been putting on a splendid show and will be visible for a while yet. Alan Tough’s image taken on January 1 using a robotic telescope situated in New Mexico shows it well.

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |