Reginald Lawson Waterfield (1900–1986), eclipse chaser & comet photographer extraordinaire: Part II: 1939–’86

2021 July 31

World War II

During 1939 May, Reggie received a grating ruled by Prof Wood at Johns Hopkins University. Frustratingly, he had just completed testing of the grating on bright stars when the War put a stop to all of his astronomical work.102

Fittingly the God of War, Mars, would reach opposition on Jul 23, with its diameter reaching a maximum of 24 arcseconds four days later. Reggie lamented the planet’s southerly declination, but encouraged BAA members to observe it nevertheless.103

The BBC asked Reggie to present a 10-minute programme, at 10.25 p.m. on Jul 26, about the Red Planet being at its closest to Earth. Remarkably this programme was transmitted live, not on BBC Radio, but on BBC Television!104 It was just as well that Mars was not peaking five weeks later because on Sep 1, the plug was pulled on BBC television transmissions due to the imminent declaration of war with Germany. TV broadcasts would not resume for seven years; it was feared that the VHF transmissions could act as a homing beacon for German bombers. Regular TV transmissions had been in operation for just three years and the Alexandra Palace transmitter could only reach out to a radius of 25 miles and 25,000 customers.105

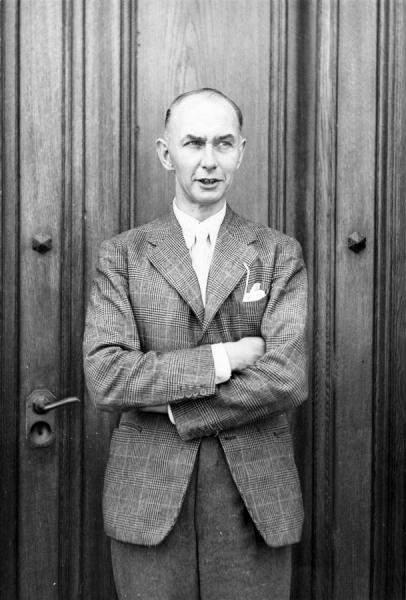

From 1940 September, the Luftwaffe commenced their bombing of London. Reggie reported that ‘the preparation of the interim report dealing with the 1939 apparition [of Mars] has unfortunately been held up by work of a more urgent nature’.106 He was initially roped into the Emergency Medical Service, carrying out valuable work with sector haematology and air-raid resuscitation.107 During late 1940, he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), working in the British Army Blood Transfusion Service, and by the end of the summer of 1942 he had formed a blood supply base unit which operated in North Africa, advising and caring for the needs of the mobile field transfusion units under his command (see Figure 19).108

During Reggie’s wartime absence, the BAA Council drafted his friend Percy into service as the interim Mars Section Director.109 Remarkably, just before he departed for Africa with the British Army, Reggie managed to complete the manuscript for another book: a compact ‘pocket handbook’ 206 pages in length and with 30 diagrams, entitled The Revolving Heavens: Astronomy for Observers with the Naked Eye. On the inside of the front cover he wrote: ‘The black-out which darkens the night skies has brought large numbers of people to take an interest in the many things in the heavens they may see for themselves without a telescope’.

At the start of 1942, the Council of the Royal Astronomical Society awarded their Jackson-Gwilt Medal and Gift to Reggie.110

During 1943 Reggie was wounded. He was then invalided out of the Army and returned from North Africa, via Italy, to the UK, resuming his duties at Guy’s Hospital by the start of 1944.111

The BAA and the RAS provided a series of lectures for members of the armed forced during 1944 and 1945. Reggie delivered his talk on 1945 Feb 9, on the subject of the planet Mars.112 Ten days later, Reggie was back on BBC Radio, on the Light Programme. In a 15-minute programme entitled Book Talk, transmitted at 6.30 p.m. on Feb 19, Reggie gave a short review of the latest scientific books.113

After the War

Regarding the disruption which the War years wreaked on his observing, Reggie wrote the following in his logbook during 1948 August:

‘Owing to outbreak of war and my virtual absence from Headley no further systematic observations were made at Headley after [1939] Jul 12. I occasionally visited Headley for the odd night during 1939 & 1940 & on such occasions used to see [T. E. R.] Phillips in the observatory. But about this time Phillips retired and went to live at Tadworth and owing to his failing health his own journeys to the observatory became infrequent. In 1940 I joined the Army & shortly after that Phillips – one of the greatest visual observers – died. By going ‘absent without leave’ I managed to attend his funeral & nearly got shot. It was a lovely afternoon in Headley churchyard and all the cricket team attended in their white flannels for TERP was a most enthusiastic supporter of the game. After that I did not visit the observatory again until about 1944 – when, a day or so after my return from Italy, a ‘doodle-bug’ fell very close to the rectory, landing uncomfortably close & doing a certain amount of structural damage to the three observatory buildings (some hundred yards away), without fortunately damaging the instruments. With the aid of Marshall, the gardener, I made the damaged buildings waterproof until 1948, when the Royal Observatory kindly took down the instruments and buildings: mine was relocated in Ascot, the 8-inch refractor was sold to the South African Govt., and the 18-inch & 12½-inch reflectors were sold privately.’

[In fact, the 18-inch mirror was already on loan from the BAA and Phillips’ 12½-inch was purchased by the BAA in 1945. – MM]

From Headley to Ascot

So, after the War, Reggie decided he would move his astronomical equipment a distance of 20 miles (32km) from Headley to a promising site at Silwood Park, Sunningdale, near Ascot, where his sister Patsy and her husband Charles ran the elite Heatherdown preparatory school for boys.

The Silwood Park and Ashurst site had been acquired by the Imperial College of Science & Technology in 1947 as a Biology Field Station. Reggie managed to get permission from Prof J. W. Munro, the Field Station Director, to build his private observatory on the park. Munro also gave Reggie the use of a concrete hut for use as a darkroom and workroom.114–116 Reggie moved into a big house that was suitable for his requirements, named Hereford (his father had been the Dean of Hereford). The house was on Swinley Road, Ascot, just a few miles from the planned site for his new observatory. So, once the War was finally over, he started moving his 6-inch Cooke refractor and 6-inch ƒ/4.5 astrograph from Headley to Silwood Park, as well as reconstructing his observatory. In the 1940s, the site was far enough from London for the skies to be reasonably dark and it had very good horizons.

During 1948, Reggie finally got the equipment up and running again. He built a measuring microscope and also borrowed BAA instrument no. 101: the blink microscope made by Will Hay. This weighed about 70lbs and had been donated by the comedian after his health declined. Hay would die on 1949 Apr 18.117

Equipment advice

By now Reggie was an expert at aligning a big equatorial mounting on the pole and his advice was often sought. He recommended the following:

‘While there is usually a fine adjustment – with push-and-pull bolts – for altitude, there is often no such fine adjustment for azimuth: one is expected to take a hammer and knock the upper part of the pier round on the lower part, and thus achieve an accuracy of a few seconds of arc! Although this may sound ridiculous, it is really perfectly easy. The secret is to make a large number of very light taps with the hammer; one can then literally [sic] move a star through a few seconds of arc in the field of view and bring it back again on to the cross wires. For this purpose, one is supplied with a stout metal pin which plugs into a hole in the upper movable part of the pier, and it is this pin which is tapped with the hammer.’

He also had some advice regarding keeping eyepieces in pockets, which some observers, like Ryves, practised to keep dew at bay: ‘…the lenses get scratched if you keep keys or coins there as well. If you have a couple of eyepieces, it is easy for the brasswork of one to scratch the lenses of the other. Micrometer eyepieces are very easily scratched.’118 As for offset-guiding on a comet, by moving the guide star along a micrometer wire attached to a refractor guidescope, Harold Ridley often quoted Reggie’s simple ‘rule of thumb’, which removed any doubt: ‘Move the star the same way that the comet is moving in the sky’.119

An invention & comet photography resumes

During 1948, Reggie invented the monochromatic halometer and published details in the Lancet.120 In Reggie’s design, a monochromatic light source was viewed through a film of blood, resulting in a halo. A perforated screen with a pinhole pattern aligned with the halo was then adjusted and the screen position could be interpreted as the blood cell diameter.121

From 1948 Aug 11 to 18 Reggie was in Zürich, Switzerland at the seventh General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union (see Figure 20).

On returning to the UK, his logbook records his first serious tests of the equipment at Ascot on 1948 Aug 29, with polar alignment tests continuing into October and a test photo of the UV Persei field being exposed on Nov 6. The minor planet 192 Nausikaa was captured on 1949 Jan 1 in Perseus, and a polar sequence photograph was exposed. In addition, on Jan 1 & 8 he captured images of the so-called ‘Eclipse Comet’ (C/1948 V1). He also took two photographs of the 14th-magnitude C/1947 S1 Bester on 1949 Jan 29 and Feb 19.122

(Login or click above to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/MobFig19_RAMC.JPG

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/MobFig19_RAMC.JPG

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |