Roland L. T. Clarkson: a Suffolk astronomer

2020 March 30

Introduction

Introduction

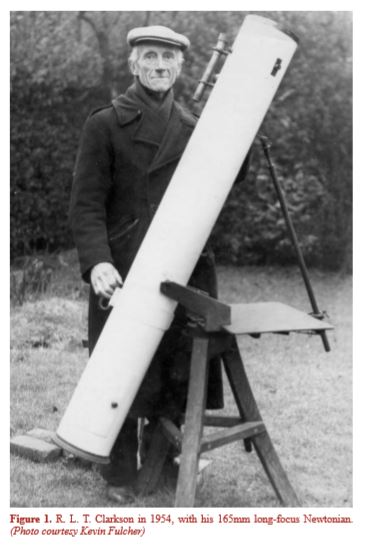

Most modern astronomers will be unfamiliar with Roland Lebeg Townley Clarkson (1889–1954; Figure 1),1 but for decades Clarkson supported many of our Observing Sections. Living in rural East Anglia he had the advantage of really dark skies for many years.

What makes him especially interesting is the complete series of 18 beautifully written and illustrated notebooks that he left.2 These cover 1906–’53 and reveal in detail the astronomical work of a man who was very much just an ordinary amateur; a far more typical figure than the advanced amateurs who made up the ‘Headley Group’,3 or Robert Barker’s ‘Circle’.4 The author came across these notebooks when cataloguing the Association’s Archives as long ago as 1981, and has always wanted to tell Clarkson’s story. This paper does just that.

Clarkson’s father was Laurence T. Clarkson,5 the second son of the Rev. L. T. Clarkson, who had been Rector of St. James, South Elmham. Laurence Clarkson was born in 1857 and later served as Chairman of Wangford Rural District Council. As a surveyor, estate agent and farmer he is associated with the St. James Post Mill, which was the last post mill in Suffolk to be moved (in 1864) and set up as a corn mill.6 (The mill was dismantled within his lifetime.)

Together with his brother A. Townley Clarkson, Laurence was well known in yachting circles, owning a barge which he had built in 1899, Spider, and the houseboat Coot. He was a member of the Royal Norfolk & Suffolk Yacht Club. He married Annie Payne, another clergyman’s daughter, in 1879. Laurence and Annie had one child, the subject of this biography, in 1889. Annie died the following year and Laurence with his baby son went to live in Beccles. It was natural, therefore, that Roland Clarkson was educated at that town’s grammar school. He amassed a long list of addresses in Suffolk and its neighbouring counties, and spent a number of years in ‘Constable Country’.6

We know that Clarkson had some scientific training, particularly in chemistry, for he made good use of it later. He had various jobs during his working life: the final ones were clerical (involving politics or business) but most early ones were technical. Like many amateurs he used a 76mm (3-inch) refractor for a number of years, but graduated to larger reflectors, eventually concentrating upon a 165mm (6½-inch) Newtonian. He sometimes interacted with better-known amateur astronomers, in particular the lunar observer H. G. Tomkins. Figure 2 shows Roland Clarkson in 1927.

Our subject never married and his obituarist described him as leading a solitary life, while always ready to encourage an interest in astronomy and a prolific correspondent. However, that is a sketch from old age, and a cursory reading of his logbooks will show that he often sought company.

Early astronomical work, 1900–’12

Early astronomical work, 1900–’12

During this period, the young Clarkson observed with the naked eye and nothing larger than a 38mm (1½-inch) Dollond look-out telescope (essentially a spyglass with a three-pull drawtube and a power of ×12).7 The Dollond belonged to his father, who was always referred to as ‘L. T. C’. There are a few references to ‘Uncle A. T. C’.

‘The first important astronomical event which I recollect was a lecture by Sir Robert Ball at the Memorial Hall, Beccles, in I think 1905’, he wrote in a letter to fellow amateur D. J. Fulcher in 1951.8 Was this lecture the catalyst for his astronomical career? Formal recorded observations began on 1906 Jan 8, when Clarkson was aged 16 and living at 10 Pier Terrace, Lowestoft (although he recalled having seen the solar eclipse of 1900 May 28 while still at school). The logbooks recall not only his observations, but other astronomical events and meetings, as well as newspaper clippings. ‘In 1907 a course of six lectures under the auspices of the Cambridge University … was given at the Town Hall at Lowestoft by the Rev. T. E. R. Phillips [Figure 3A] who [later] was Rector of Headley near Epsom, and a well-known Director of the Jupiter Section of the BAA.’ Phillips was reputedly a very enthusiastic speaker,9 and the young Clarkson must have been excited by the talks.

Clarkson saw the transit of Mercury on 1907 Nov 14 from 48 Denmark Road, Lowestoft. He saw the comets of 1910 & 1911, including Halley’s and the Great January Comet C/1910 A1, as well as several eclipses of the Sun and Moon. Clarkson was clearly good at creative tasks, and in 1909 from the Mars observations of Percival Lowell he fashioned a canal-laden globe of the planet out of wood. Later he would model lunar craters from plaster.10 A reference to the large partial solar eclipse of 1912 Apr 17 records that he watched it from Beccles aboard Coot, his father’s houseboat.The low power of the Dollond limited Clarkson’s observations. By way of compensation, the night skies were very dark. Fortunately another local amateur had a 76mm (3-inch) refractor, which Clarkson was able to share. He records: ‘James Blyth, who was the author of a number of novels dealing with Suffolk fishermen and natives, Juicy Joe, Celibate Sarah, Deborah’s Life, The Same Clay, Amazement, Rubina, and others never heard of now I suppose, lived at Pakefield near Lowestoft, and about 1908 bought a 3-inch telescope from Newton and Sons for £5 new, with which he and I used to observe Jupiter, Saturn, [the] Orion Nebula, people on the pier, and other things, but I do not think he did much serious astronomy’.8 Blyth turns up in the earliest notebook.

A few records from this early period stand out as being of unusual interest, so we mention them separately.

(Login or click above to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/McKim1.JPG

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/McKim2.JPG

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/McKim3.JPG

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |