Searching for sky

2023 August 10

My story began with a photo.

I was reminiscing over an old photo album and found a picture of me dating back to 1978 February, carrying a tripod in the snow while climbing Mount Korek in northern Iraq (2,160m). I was a student of Physics at Baghdad University when I was selected to take part in a programme supervised by Prof Merle F. Walker, University of California (Lick Observatory), to site-test a couple of mountain tops for the ambitious Iraqi Astronomical Observatory.

Just before its completion in 1985, the observatory was hit and partially destroyed by Iranian fighter jets during the Iran-Iraq war and the domes were further targeted by US planes in 2003. This ambitious project to operate the 3m and 1.2m mirror telescopes, along with a submillimetre radio observatory, came to an abrupt end.

This photo brought back some old memories of my early days of astronomy in Iraq, back when I was 15. I recently looked at the photo again and said to myself: I am no stranger to this experience. The warmth of love for this beautiful hobby rekindled in me and I resolved to continue climbing the mountain to find a suitable site for the establishment of an observatory, albeit a modest one.

At the beginning of 2019, I revisited northern Iraq, only to discover that Mount Korek, where the remnants of the destroyed domes are still shining with glory, had turned into a tourist destination, while the mountain peaks were beyond reach of the public and had become personal property to the heads of political parties.

Though frustrated, I refused to pull the shutter down on my exciting experience. I bought my first telescope in the UK, and decided to look for a new overseas destination that I could easily reach, with more clear skies and less light pollution than my rainy UK hometown of Manchester, and most importantly, a stable government.

Why Agadir, Morocco?

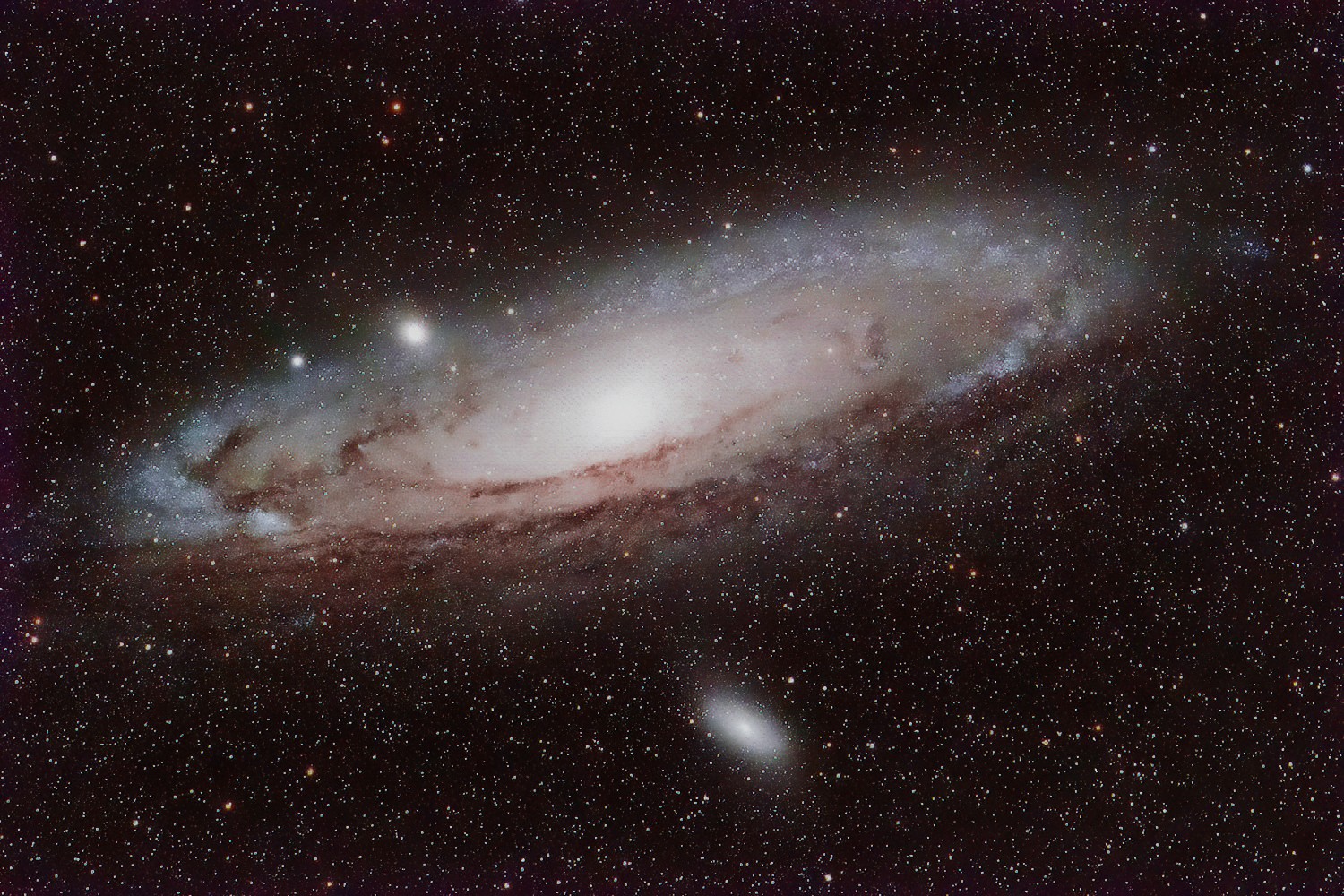

First, because it is at latitude 30°. I have special affinity to latitude 30°: it is where I lived my childhood and teen years in southern Iraq. We always slept on the rooftop during Iraq’s hot summers. Light pollution back then was minimal, and I used to see the Milky Way on every moonless night before going to sleep. I vividly remember how rich the Sagittarius region was, and how easy it was to spot the Andromeda Galaxy every night and show the rest of my family.

Secondly, Morocco shares the same time zone with us in the UK, and for most of the year the same time. Thirdly, Agadir is a close and relatively cheap destination for UK travellers, and the Atlas Mountains around the city provide ideal spots with low light pollution. Lastly, because I can easily communicate with Moroccans in Arabic (and now understand their colloquial Darija). An added bonus is that I love Tagine, the famous Moroccan dish.

When I first started, I did not know anyone in Morocco at all. I took advantage of social media to pitch the idea and find friends who could help me with the task of finding an ideal site to set up an affordable observatory. I was astonished by the extent of popular excitement and the hosting offers that I received. There was even competition between villages to offer generous help so that I could test their sites.

Mount Tojrart

My first trip in 2019 March was to Mount Tojrart (1,380m), with Bortle 2/3 sky and only one hour away from Agadir airport. I drove towards the summit with my very enthusiastic Moroccan friend Abdullah, a first-year Physics student. At its highest point, there was a monastery-like Islamic school that was built hundreds of years ago. People there were very generous, and the Sheikh of the madrassa was super excited about the idea of building an observatory.

They offered us a room to sleep in and provided everything we needed to set up my small telescope. We found a nearby circular stone area, apparently built to be a spiritual isolation spot. How compatible with stargazing!

Stargazing on this mountain was an amazing experience. I was surprised that a mere four minutes’ exposure of the Andromeda Galaxy revealed details that required at least two hours back at home. We almost decided that this was the perfect site, were it not for some surprises.

The authorities

Morocco consists of two often contradictory parts: the people vs. the government authorities. The Moroccan people, especially the Berber (Amazigh) villagers, are very generous; they interact with new projects in their villages with enthusiasm and love to offer help. However, the government authority is quite the opposite. It is a security-focused bureaucracy that is always sceptical of anything new. Foreigners are welcome as tourists on the beach and historical towns. But if they wander far into mountains and villages they will draw immediate surveillance, unless they came as part of a tour group to designated areas.

In 2019 November, while I was photographing comet C/2019 L3 (ATLAS) from my beloved Tojrart summit, a security employee came to tell me that I needed special permission from the authorities to be able to continue my activities. He insisted that I should disassemble the telescope and leave the mountain immediately, or else I would be arrested.

In the morning, a senior village security officer (the commander) was awaiting me at the hotel. I was instructed to visit the security headquarters in a nearby town. After I explained that I would like to build an observatory, they told me that I needed approval from the right department at Ibn Zohr University in Agadir. However, when I spoke with the University, they asked me to get permission from the authorities first. At this point, I realised that it is almost impossible to obtain any kind of official permission for this specific area, so I decided to expand the scope of my search to other sites.

Tadrart village

I went back to social media. This time, I stipulated that those who wish to host me should obtain the official permission first. I received an amazing offer from Saeed, the director of an association that offers accommodation to students who come from far-away villages to study at the only school in the area. Tadrart is two hours north-east of Agadir.

In early 2020, I had a wonderful week in this village, hosted and fed in the students’ dormitory. I even gave practical stargazing sessions to the students living there.

It was not a particularly mountainous area, and it got quite hot in summer. Also, despite its distance from light pollution, the glow of the city of Agadir was somewhat affecting the south region of the sky – an important factor in site-testing for an astronomical observatory.

The offer to establish a permanent observatory there is still valid, but I decided to expand the search base, to gain better height and less light pollution.

Abdul-Latif (Abdo)

Abdul is an enthusiastic young Berber who finished high school and was unable to enter university or find a job. He loves astronomy and has shown a strong desire to learn new skills. He was overjoyed when I chose him to accompany me throughout my trips.

As he is fluent in Tamazight language and knows the customs and traditions of villages, his presence with me was of great benefit. His family, who lives in a modest country house, offered me great help by hosting me whenever I visited Morocco. Frankly, I am no longer the strong young man who once climbed Korek holding heavy items, but he mastered how to dismantle and set up the telescope while we moved between different sites.

Takdhisht Village

Emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic in the summer of 2021, my friend Abdo invited me to visit the village where he was born, nested deep in the Middle Atlas mountains. I could not resist this temptation. I had learnt by now how to observe secretly, then quietly withdrew from the area before the news spread to the authorities that a suspicious foreigner was lurking around. It was an amazing experience, in a village where everything was natural and organic. No one in the village ever wore masks during COVID-19 or got infected; they told me, ‘Oh yes, we’ve heard about this pandemic’!

Every evening after they performed their evening prayer, which coincides with the start of astronomical darkness exactly, all the village lights were turned off to save energy, and a frightening darkness fell among the mountain peaks surrounding us from all sides. It felt as though we were in the middle of a lunar crater.

We would climb the mud-and-reed roof using a makeshift wooden ladder and lift the telescope and equipment to the roof with a basket and rope. At the time, the telescope did not work due to a malfunction of the power supply, but wide-angle photography of the Milky Way with my Nikon yielded great results. I also learnt a lot about life in Moroccan mountain villages.

Adar village

I had identified this village from the early days, via Google and pollution maps, as an excellent candidate for the location of the observatory. It is on a 1,860m-high plateau, Bortle 2, with no towns to the south for hundreds of kilometres.

However, I did not know anyone there to host me until I met Mustafa, a keen footballer who dearly loved his village. He wrote to me with an offer to host me for five days in his house. The great thing about Mustafa is that his older brother is a member of the local authority, so I did not face any security issues.

I headed to his village, three hours from Agadir, at the end of 2021 November. The night sky was truly amazing, especially when the mighty Orion rose high. My presence there coincided with the passage of comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard), close to the Messier 3 globular cluster. The nights were freezing and the village houses had no means of heating, due to high energy prices in Morocco. These were some of the coldest days of my life; I slept in my jacket and my shoes under three layers of woollen blankets.

I found an empty piece of land in Adar that belonged to the local authority. It could potentially accommodate more than 10 observatories. It is so rare to find a location as ideal as this, where electricity, water and most amenities were readily available. The Internet signal there is stronger than at my house in Manchester.

The locals were very excited about the idea. I succeeded in interviewing the deputy governor of Taroudant municipality and presented them with my project. They sounded interested, and we are waiting to hear back on whether they approve.

My ultimate ambition is to acquire the land in Adar in order to offer an ideal location for those keen on erecting their observatories at a very modest cost, and to also provide amateur astronomers with a safe and amazing location when they come for tourism in Agadir.

My remote telescope

While we are awaiting the outcome of our application, Abdo and I have decided to set up my small telescope permanently on the roof of his country house, in a village 45 minutes’ drive from Agadir with a Bortle-4 sky – not too bad. In order to ensure fast and unlimited connectivity, we installed a receiver of optical-cable Internet from the main city. The telescope, camera focuser and filter wheel are all connected to a fast laptop that I left there. Using Team Viewer, I can control all the operations of the telescope from my room in Manchester.

My setup is not fully robotic, and it does not need to be. At the start of each clear night, Abdo uncovers the telescope; he then covers it again when he wakes up for the dawn prayer, just at the start of morning twilight. He helps me to polar-align from time to time. When I am busy or exhausted, I write a list of targets and exposure times for him to follow. During the day, I transfer all the frames to my laptop in Manchester for processing.

(Log in to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |