Sky Notes : 2022 October & November

2022 October 1

The nights lengthen, British Summer Time ends, the centre of our Milky Way galaxy dips into the south-west, and we can begin to peer out through the clearer path perpendicular to the galactic plane into the autumnal realm of galaxies.

We also welcome the return of the most popular planets to the evening sky, compensating for the rather barren skyscape that the glorious summer constellations are slowly vacating. Saturn in Capricornus and then Jupiter in Pisces occupy the southern aspect during mid-evening in October and November respectively, and while the ringed planet remains rather low, Jupiter is now splendidly placed. Mars also becomes prominent in the east, dominating the scene by the end of November.

The Summer Triangle remains a useful guide during early autumn as it hauls the Milky Way to the west, but the dominant signpost of this

season is the Great Square of Pegasus: the large asterism that lies on the meridian at mid-evening in early November. The western stars of the Square, Scheat (beta) and Markab (alpha), point south to Aquarius and on to the most southerly first-magnitude star visible from the UK, Fomalhaut (alpha Piscis Austrini). The eastern aspect has Alpheratz (delta Pegasi, or more commonly alpha Andromedae) and Algenib (gamma Pegasi) guiding us through Pisces the fishes, to the tail of Cetus the whale, marked by Diphda (beta Ceti). But this year the scene is dominated by brilliant Jupiter, dazzling at magnitude –2.8.

Pegasus is the seventh largest constellation. The number of stars that the observer can see within the large Square is often regarded as a guide of sky transparency and light pollution. How many can you see?

Although Pegasus has the splendid globularcluster Messier 15 to its extreme west, near the bright star Enif (epsilon Pegasi), it is the splendid array of galaxies that generally attracts the deep-sky observer. One of the best is NGC 7331 and its family group, sometimes known as the Deer Lick Group. It is a bright spiral seen at an angle of 22 degrees, with four smaller galaxies in the field. If at the currently measured distance of 45 million light-years, NGC 7331 is one of the largest spirals in our supercluster, rivalling the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31). The small galaxies that seem to be associated with it are in fact background objects and much more distant, being between 290 and 365 million light-years from us.

To find NGC 7331, begin with Scheat, the north-western star of the Square. To its west is Matar, eta Pegasi. A short hop to the north-west of Matar will locate this fine galaxy. In passing, the unusual ‘Deer Lick’ nickname refers to the site in North Carolina where experienced American amateur Tom Lorenzin had a particularly fine view.

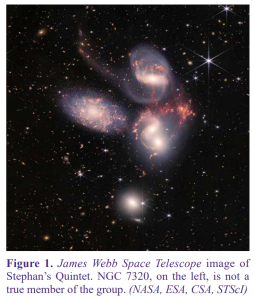

Just south of NGC 7331 is an added bonus, recently made famous by the first release of images from the James Webb Space Telescope. The small group of galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet lie a short distance south of the NGC 7331 group. NGCs 7319, 7318a, 7318b, 7317 with 7320 make up the quintet and form Hickson Compact Group 92. While four of the galaxies are at a distance of around 300 million light-years, NGC 7320 is much closer at around 40 million light-years and is possibly linked to NGC 7331.

This time of year is perfect for observing our own little family of galaxies: the so-called ‘Local Group’ that occupies a ten million light-year diameter within the supercluster. Our Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy dominate the group, being large spirals. The more lightweight spiral Messier 33 (the Triangulum Galaxy) completes the spirals, the remaining 50 or so group members being dwarf elliptical or irregular galaxies, many of which are satellites of the great spirals. Several are on show through the autumn and can be fun to locate. Messiers 32 and 110 are easy targets as companions of the Andromeda spiral and are bright ellipticals; NGC 147 and 185 are also companions of Messier 31 but lie in Cassiopeia. They are more elusive but can be captured in the same low-power field. Sweep north-west from the Andromeda Galaxy towards Shedir (alpha Cassiopeiae) and the 10th-magnitude pair of ellipticals should be glimpsed on the most transparent nights. A tougher target is IC 1613 in Cetus: a dwarf irregular that remains in pristine condition, being untouched by the bigger bullies in the group as it lies on the periphery. Although magnitude 9.9, it is 16×14 arcminutes so is of low surface brightness.

To the east and becoming prominent as autumn deepens are the zodiacal constellations of Aries the ram and Taurus the bull. Aries has little to offer but Taurus is splendid, with its famous clusters the Hyades and Pleiades, the Crab Nebula (Messier 1), and the Taurus Dark Cloud – the nearest molecular cloud to us – with its young stars forming, notably T Tauri and Hind’s Variable nebula (NGC 1555). This year, the bull is dominated by Mars, which ends its eastern progress to become stationary on Oct 30 and then begins its retrograde passage west through the horns of the bull, on its way to opposition on Dec 8.

By the end of November, Orion and his retinue of brilliant winter stars are well up in the east, with Perseus at the zenith and Auriga climbing. However, Mars is likely to be a wonderful distraction over the early winter months.

The solar system

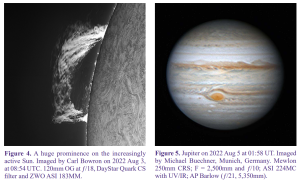

British Summer Time ends on Oct 30. The Sun has been excitingly active during the late summer and should continue to provide much of interest. Large and complex sunspot groups have been recorded and imaged, as have some spectacular prominences (see Figure 4).

We can enjoy a partial solar eclipse on the morning of Oct 25 (see p.273). Beginning soon after 09.00 UT (exact times depend on location), the new Moon will bite a chunk from the northern aspect of the Sun. The eclipse is not total from anywhere on the globe, so there is no need to travel.

There is also a total lunar eclipse on Nov 8, none of which can be enjoyed from the UK. The eclipse will be seen in its entirety from the

western USA and Far East, although some of it will be seen across the Americas, the Middle East and Australasia. Mercury has its best showing of the year in the mornings of early October, reaching greatest western elongation and an altitude of 11 degrees on Oct 8. Thereafter it rapidly descends to reach superior conjunction on Nov 8; it is too low for observation from the UK thereafter. Venus will no longer be available as it reaches superior conjunction on Oct 22.

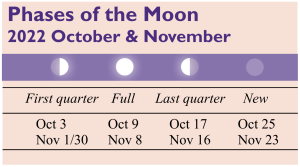

Mars begins to retrograde from Oct 30 in eastern Taurus. It rapidly brightens as Earth catches it up on the inside lane, glowing a bright orange in early October at magnitude –0.7 and reaching –1.8 by the end of November. The gibbous disc swells from 12 arcseconds to a fully illuminated disc of 17.2 arcseconds. The South Polar Cap should be all but vanished, but the North Polar Cap should be visible. Whether there will be major dust storms remains to be seen. Opposition is on Dec 8, when the full Moon occults Mars. Jupiter is only a few days past opposition in early October and remains brilliant in an area devoid of bright stars, lying between the tail of Cetus and Circlet of Pisces. The large disc (almost 50 arcseconds at the beginning of October) should provide much detail, including the famous Great Red Spot which has somewhat diminished over recent years. The dance of the Galilean moons is a delight as always. Saturn passed opposition on Aug 4 and so will be best observed in the early evening, before it dips too low in the west. Uranus reaches opposition in Aries on Nov 9 when magnitude 5.6 and 3.8 arcseconds in diameter. It is unusual to see any detail but spotting the larger moons can be a fun challenge for owners of larger telescopes.

The four brightest (Titania,Oberon, Ariel,and dark Umbriel) are between 13.8 and 14.8 in magnitude at opposition, dotted like sprites around their parent body. Neptune was at opposition on Sep 16 so is well placed in Aquarius, not far from Jupiter. It is magnitude 7.8 so binoculars or a telescope will be required, and its 2.8-arcsecond disc will need high magnification. Despite its much greater distance from us, Triton, the fifth largest moon in the solar system, is brighter than all the Uranian satellites. Asteroid (3) Juno (magnitude 9) lies halfway between Saturn and Jupiter within Aquarius; (4) Vesta (magnitude 7.3) is to the south-east of Saturn, low in the same constellation.

Meteors

The Orionids peak on Oct 22. Best seen after midnight, once the radiant between Betelgeuse and Alhena (gamma Geminorum) has risen in the east, the shower is quite reliable and derives from Comet Halley. The Moon does not interfere. The Southern Taurids are normally at their best on Nov 5 but not only are the annual fireworks a nuisance, but a gibbous Moon also spoils the show. The Northern Taurids peak a week later on Nov 12, but the waning gibbous Moon is nearby in eastern Taurus so continues to interfere. Finally, the Leonids maximum on Nov 18 is also a victim of our Moon, which rises in the constellation just after midnight.

Comets

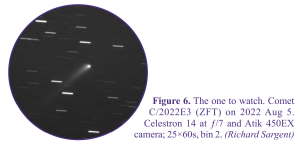

Although a rather barren time for comets, C/2022E3 (ZTF) is well worth watching. During October and November, it is situated in Corona Borealis and hopefully brightening steadily. Perihelion is on 2023 Jan 12; it becomes circumpolar and possibly a good binocular

object. By February it might just become a naked-eye comet from a dark site, but as always, firm predictions are fraught with danger!

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |