Sky notes for 2023 June & July

2023 June 1

The short nights mean frustration unless you are a solar observer. The summer solstice on Jun 21 allows a mere four hours of true darkness in mid-England, and the situation is worse further north. Enjoying the deep sky in June is especially difficult, and this year observers of the gas and ice giants have to be resolved to getting up in the wee hours. Saturn, like Jupiter which follows it, is at a suboptimal altitude. Even Venus, stunning in the west during spring, begins to drop dramatically into the north-west although remaining brilliant. By late July, the picture improves as the nights slowly lengthen and the outer solar system’s best sights become more prominent.

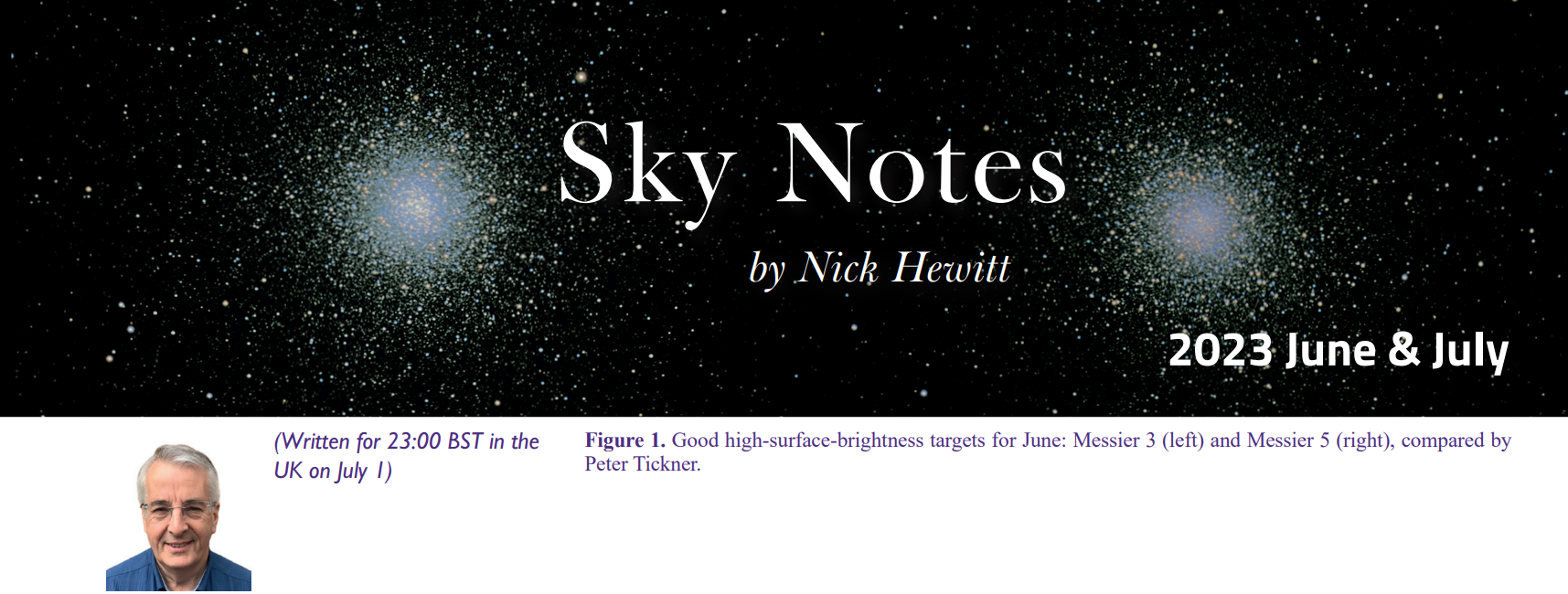

During high summer, it is best to enjoy high-surface-brightness quarry such as the numerous globular clusters that adorn the season. Early targets are the lovely Messier 3 in Canes Venatici and Messier 5 in Serpens Caput. Only Messier 13, the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules, outshines these star cities from the UK, although Omega Centauri and 47 Tucanae in the southern hemisphere are even more stunning.

Messier 3 begins the globular cluster season high in the south in late evening, located between Cor Caroli (alpha Canes Venatici) and Arcturus (alpha Boötis). A binocular or finder sweep should easily locate the core of this fifth-magnitude globular, which is a good 18 arcminutes in diameter in large telescopes. It is rich in RR Lyrae variable stars (around 222) and was also thought to have several merged old stars known as ‘blue stragglers’, although more recently many of these were found to be background quasars!

Further south-east is Messier 5, on the Virgo – Serpens Caput border. It is in a fairly barren area, although the wide sixth-magnitude binary 5 Serpentis lies just 20 arcminutes to its south-east, within a finder’s field. The common-proper-motion companion is at 10th magnitude and 11.4 arcseconds distance. The globular itself is closer to us than Messier 3, being at 26,600 light-years compared to the former’s 34,000ly distance, but although smaller in true size, it appears very similar, both appearing around 6–7 arcminutes in small telescopes but expanding to around 19 arcminutes in large reflectors. They can be stunning when fully resolved in telescopes over 20-inch aperture. Messier 5 has a more typical number of variables: some 143, of which 120 are RR Lyrae stars.

109 years ago, Harlow Shapley began studying variable stars in globular clusters, using the 60-inch reflector at Mt Wilson Observatory. Initially monitoring Cepheid variables, later he could measure the shorter-period changes in RR Lyrae stars (the ‘cluster variables’). This enabled a good estimate of their distance, thus mapping their place around the centre of the galaxy and eventually displacing the Sun from the centre of the galaxy to its position two-thirds out.

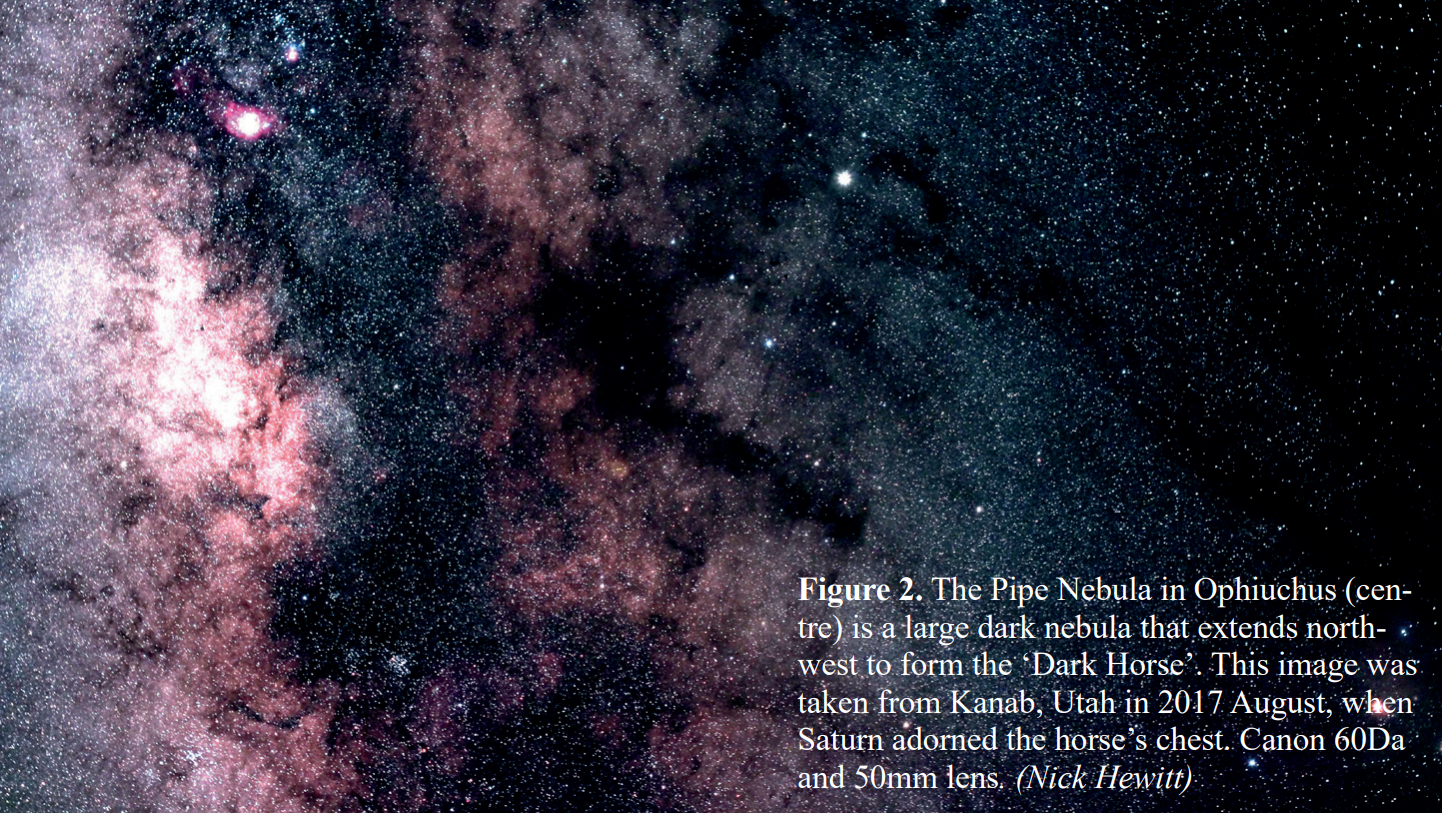

By July, the Milky Way is returning to prominence, with the swath of faint light stretching from Scorpius through to Cepheus. This is the beginning of the season to enjoy dark nebulae, made famous by Edward Emerson Barnard in the early 20th century. Barnard died 100 years ago, on 1923 Feb 6. His pioneering photography with the Bruce camera revealed the dark molecular clouds that we now realise are the nurseries for star formation.

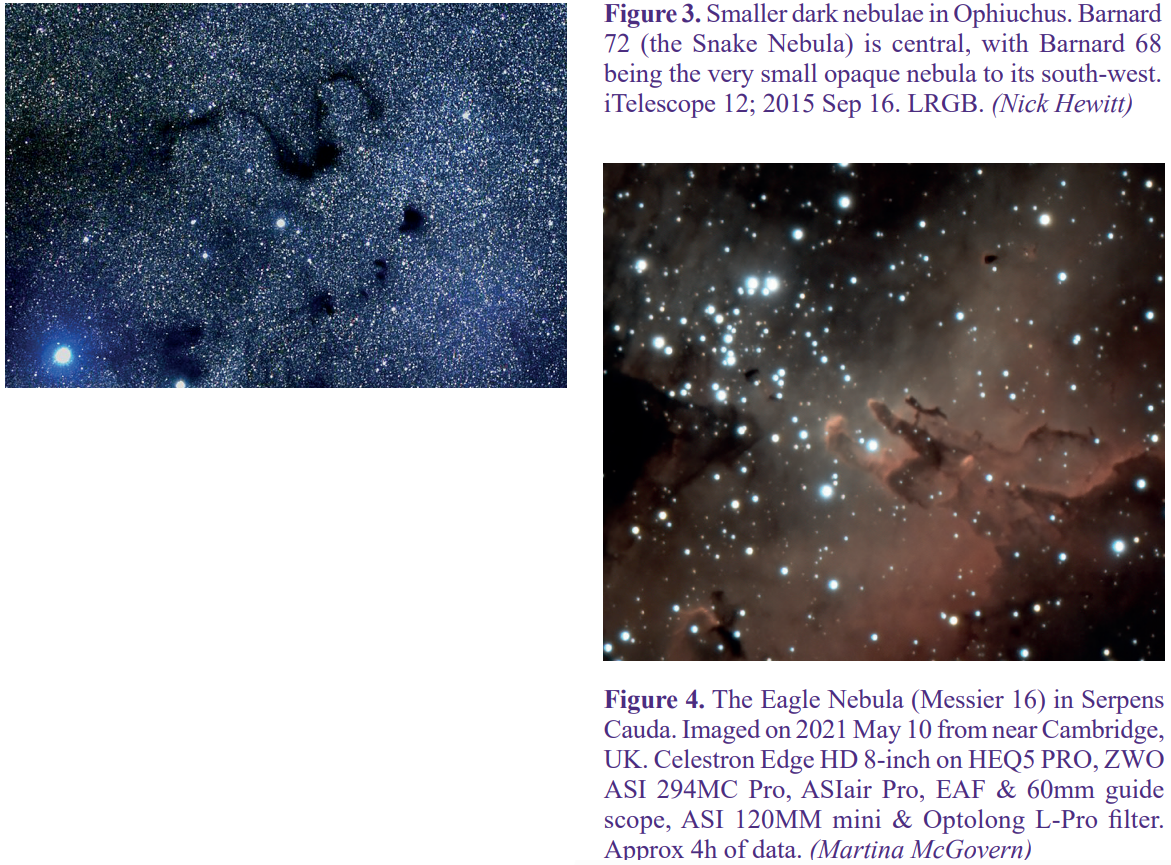

Eastern Scorpius and western Ophiuchus have marvellous dark nebulae, although their low altitude makes them challenging from the UK. Look for the large Pipe Nebula complex north-east of ruddy Antares (alpha Scorpii), that shows best on wide-field images, and extend this to show the ‘Dark Horse’, a prancing pony of a silhouette against the Milky Way. Then explore the much smaller but opaque dark nebulae Barnard 72 (the ‘Snake’), and Barnard 68: a small drop of darkness that completely obliterates the background stars. These are perfect targets for holidaymakers in southern Europe.

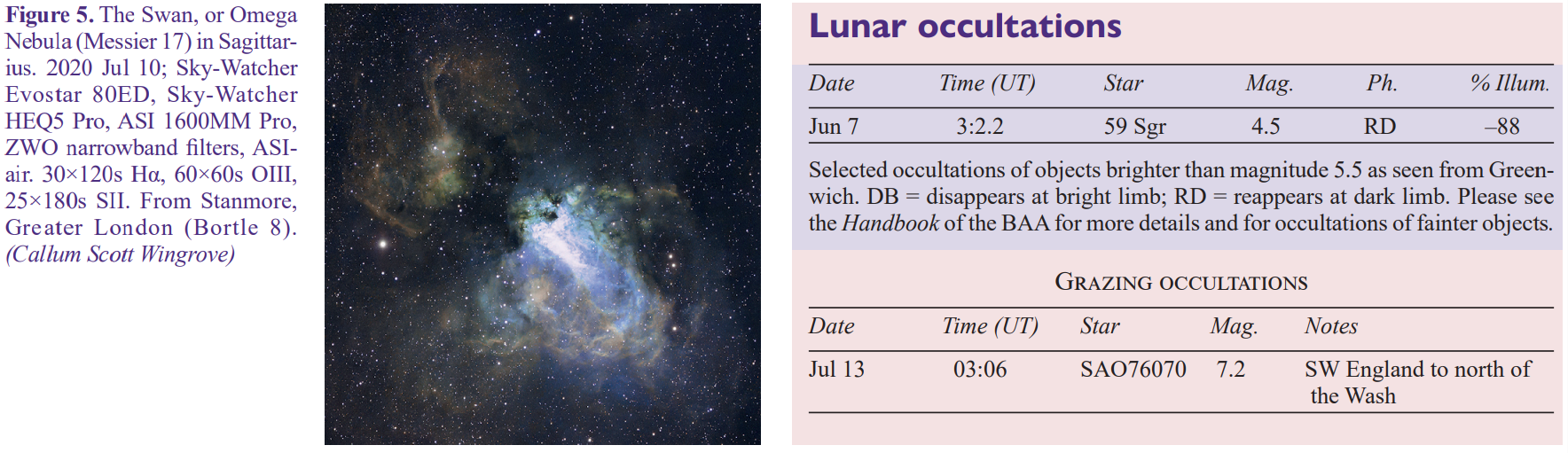

When the Moon has become less prominent in mid-July, the centre of our galaxy is on view in the south by late evening. Sagittarius never fully rises from even the south of the UK, but the Teapot asterism can just be made out above the horizon. The ‘steam’ billowing upwards from the pot contains some accessible deep-sky favourites such as Messier 17 (the Swan or Omega Nebula), and Messier 16 (the Eagle Nebula), made famous by the Hubble Space Telescope’s ‘Pillars of Creation’ image.

The Summer Triangle, formed by Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila, is now well positioned high in the east. In Cygnus we find a splendid Mira star for the novice variable-star observer: chi Cygni, which reaches its maximum during June. It then fades, but is still accessible with binoculars. This ruddy gem should be easy through both months with modest optical aid, as its mean maximum is magnitude 4.8 and its mean period is 408 days. But historically, there have been extremes of amplitude (3.3–14.2) and period (408 ± 40 days). June of this year will be too late to note the ‘bump’ in the light curve that usually occurs about halfway from minimum to maximum, where the brightness increase temporarily slows down before rising very quickly to maximum. This feature is often seen in the light curves of Mira variables with periods longer than 300 days. There is always next year!

Locate chi Cygni by sweeping from Sadr (gamma Cygni), in the centre of the Northern Cross asterism, towards the colourful double Albireo at the foot of the cross. Find chi just past fourth-magnitude eta Cygni – its warm colour should make it obvious.

The Solar System

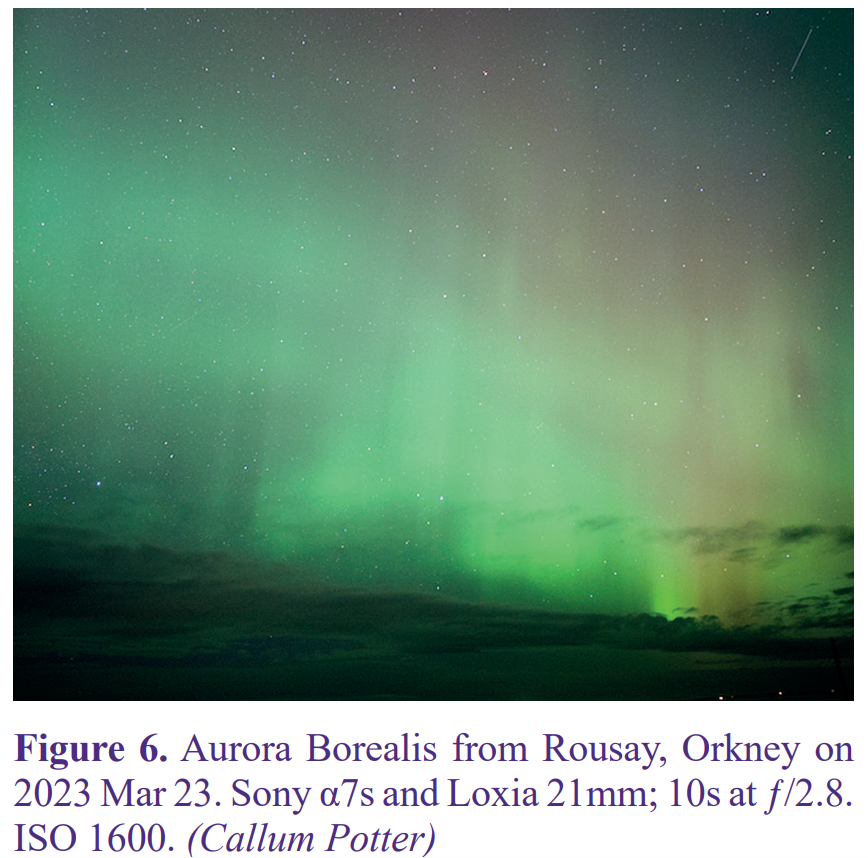

The Sun, high and hot, should remain active as it climbs towards solar maximum. Current Solar Cycle 25 began slowly but is steadily improving, and the predicted maximum looks likely to be 2025 July. The fine auroral displays seen in the spring suggest things are on track.

The are no eclipses during this period.

June and July are typically the best time for observing noctilucent clouds: high atmospheric formations, at some76 to 85 kilometres in altitude. These can be seen low in the north during astronomical twilight. Their delicate bluish luminescence is most attractive.

The planetary scene in June is one for early risers (or all-night observers), Venus being the only serious evening target.

Mercury was at western elongation on May 29, but remains very low in the morning sky before reaching superior conjunction on Jul 1. It then stays too low in the evening sky on its way to greatest eastern elongation on Aug 10.

Venus is still a dazzling –4.6 in Gemini and reaches greatest eastern elongation on Jun 4. On this day, the planet is 50% illuminated (dichotomy) and it is interesting to assess the exact position of the terminator, which should be precisely known but in fact seems to vary slightly. This ‘phase anomaly’ was first described by Hieronymus Schröter in 1793. On the date of dichotomy, the phase is marginally less than the expected 50%, the effect being more noticeable using a blue filter or when imaging in ultraviolet. Between early June and late July, Venus swells from 22 to 52 arcseconds in diameter, becoming an increasingly fine crescent as it does so. But as Venus passes through Cancer into Leo, its altitude plummets into an increasingly bright sky. Although close to Mars and Regulus in early July, this twilight makes for an unsatisfactory grouping. Inferior conjunction is on Aug 13 as Venus passes several degrees south of the Sun, but only experienced daytime observers should attempt to record this. Extreme care is required to catch this event, as the Sun is still dangerously nearby. (See Pete Lawrence and Paul Abel’s challenge on the BAA web pages, at bit.ly/41xz9OH.)

Mars is now a much-diminished planet in the evening twilight. Crossing Cancer in late May and early June, it traverses the Beehive Cluster (Messier 44) between May 31 and Jun 5. Due to the bright late-spring twilight, it is difficult to view as it is a mere magnitude 1.6, the cluster even fainter. It shrinks ever further over June and July, from 4.4 to 4.0 arcseconds. Although conjunction is still several months away (Nov 18), Mars will be all but unobservable from now on this year.

Jupiter is a morning planet, rising well after midnight in early July. It is high in Aries before dawn although opposition is still several months away, in early November.

Saturn rises before midnight by early July, now in central Aquarius. It will not reach opposition until Aug 27, but it reaches a respectable altitude in the early hours, at its best position for many years. It is magnitude +0.6 and easily identified in a rather barren area of sky. The rings are now closing, revealing more of the southern hemisphere.

Uranus remains low in Aries and is not an easy target until the autumn.

Neptune remains below the Circlet of Pisces and is a binocular object, at magnitude 7.8.

Of the dwarf planets, (1) Ceres is low in the south-west in western Virgo, at magnitude 8.6. Pluto creeps slowly eastward in eastern Sagittarius but is very low in the south. It is at opposition on Jul 22 at magnitude 14.4, lying a little south of the magnitude 9 globular cluster Messier 75. It may become easier to spot as it emerges from the dense star fields of the Milky Way into sparser regions – next year it will inhabit Capricornus. Something to look forward to!

Meteors

The June Boötids peak on Jun 28 when the Moon is at first quarter. Look for any enhanced activity that might occur as in 1916 and 1998. The slow meteors derive from comet 7P/Pons–Winnecke.

The Alpha Capricornids are affected by the gibbous Moon (full on Aug 1) on the day of their peak on Jul 30. The meteors, while infrequent, can be bright and a fireball may occasionally occur.

The Southern Delta Aquariids might put on a show on Jul 31, but again with severe lunar interference. It is worth looking for them several days either side of maximum as there can be a steady stream, albeit not a rich one. The shower may be derived from 96P/Machholz, discovered in 1986.

Comets

The most prominent comet at this time should be comet 2020 V2 (ZTF). It was at perihelion on May 8 and emerges into the morning sky, passing from Aries in early June into Cetus by early August. It will be difficult until July, but at a good altitude by early August. Predictions of magnitude are fraught with uncertainty, but it could reach magnitude 9. We shall see.

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |