Sky notes for 2026 February & March

2026 February 1

Orion is perhaps the best-known of all constellations. Even more familiar than the Great Bear, it is widely recognised by Beavers, Scouts and even Cubs. So dominant is it during the winter months that we can take it for granted, with attention often fixed on that imagers’ delight, the stellar nursery Messier 42 – the Great Orion Nebula. Yet there is far more within the Hunter’s boundaries, particularly to the east, even beyond the wonderful Horsehead and Flame nebulae.

The famous seven-star pattern is at its best mid-evening during January and February, guiding us to Taurus in the northwest, Canis Major in the southeast, Lepus immediately south and Gemini to the northeast, making Orion not only beautiful but useful too. As the constellation is available all evening, it is worth spending time searching out deep-sky quarry beyond Messiers 42 and 43.

The deep sky

Sigma Orionis (Figure 1) is an easily separated multiple star system, with a combined magnitude of 3.8. It lies below Alnitak (zeta Orionis, the eastern stellar component of the Orion’s belt) and to the west of the Horsehead Nebula. Four of its stars can be resolved, ranging from 4th to 8th magnitude, and are stunning. These are hot O-, B- and A-type stars, with the brightest, sigma1 Orionis, forming a tight binary separated by 0.25 arcsec.

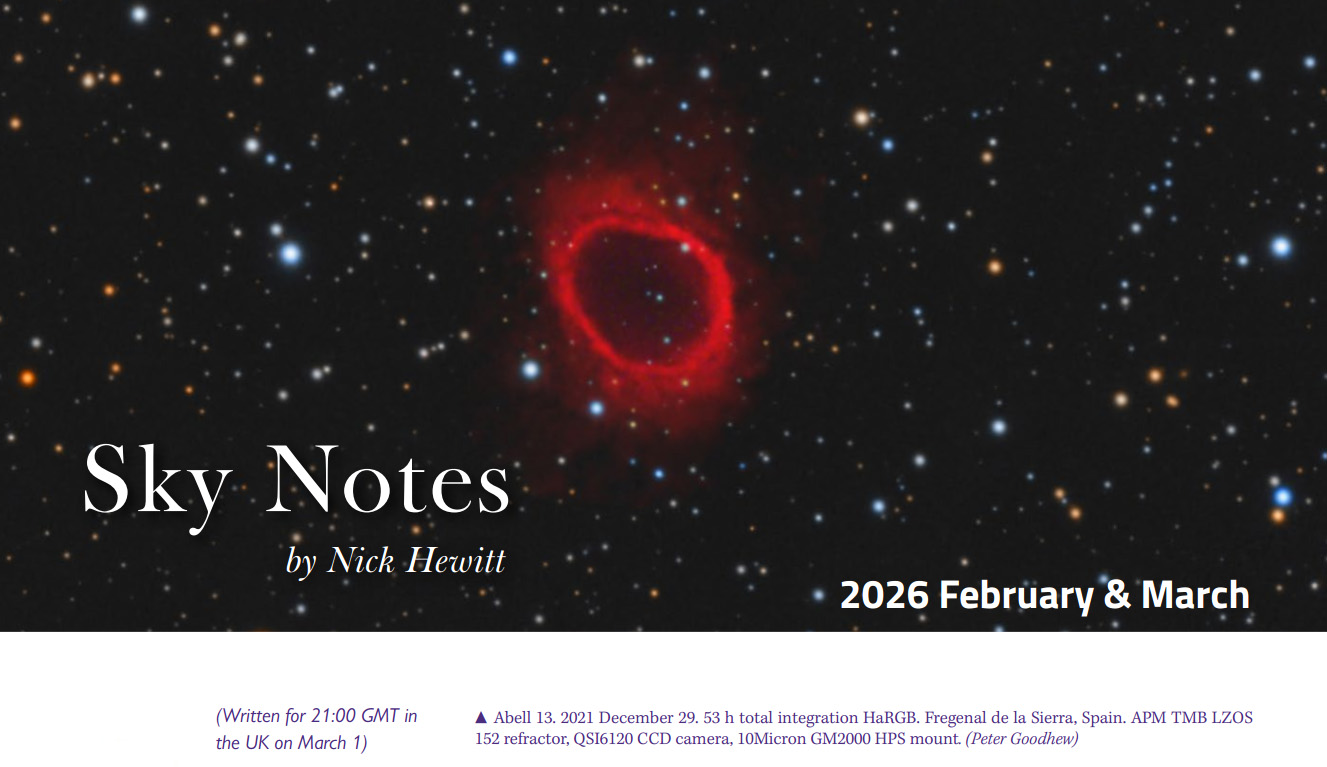

Messier 78 (Figure 2) is the third and final entry within Orion from Messier’s famous catalogue. A reflection nebula set in a dusty environment, it has an intriguing variable component to its south, best known as McNeil’s Nebula, after Jay McNeil who discovered it in 2004. M78 lies northeast of Alnitak and, at magnitude 8, is one of the easier reflection nebulae to observe, especially as it reflects the light of two O-type stars. These are the visible members of a very young cluster containing several T-Tauri-like young stellar objects revealed in infrared studies. McNeil’s Nebula itself was revealed following an outburst by the FU Orionis star V1647 Orionis (see below), but by 2018 it had disappeared, a phenomenon noted by BAA member Mike Harlow, who communicated it to professional astronomers. The area remains worth monitoring for any potential reappearance.

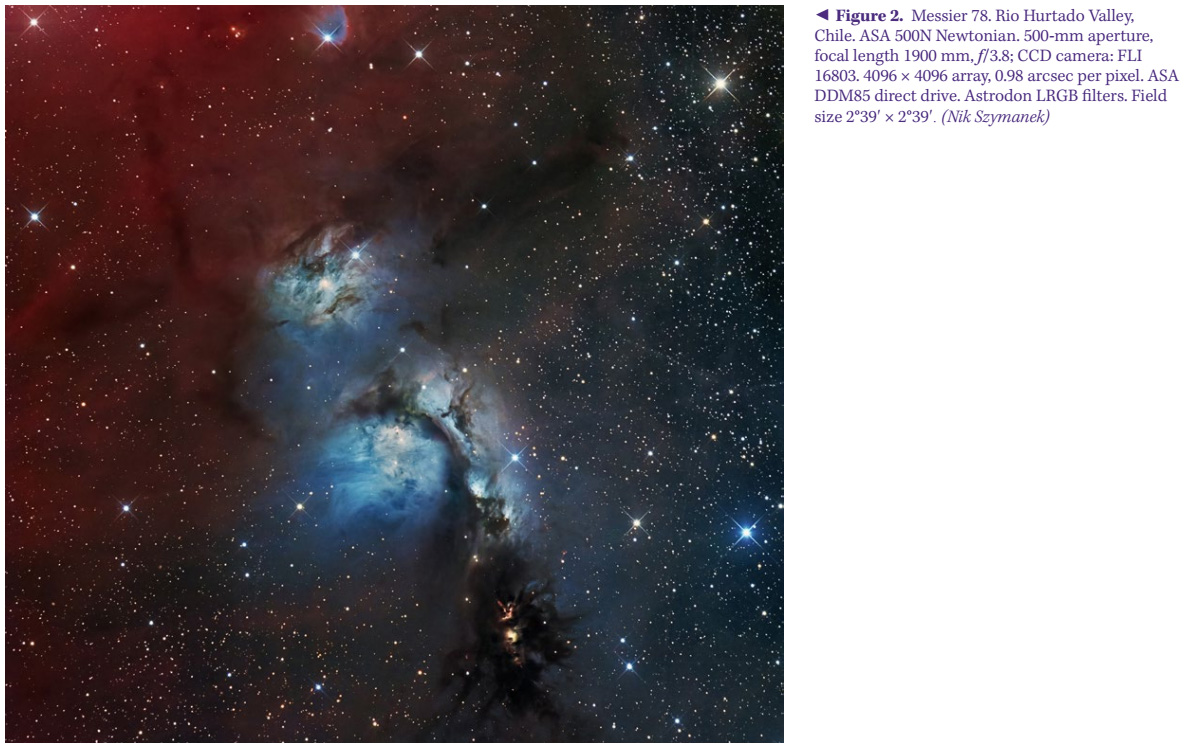

Barnard’s Loop (Figure 3) is a vast swathe of emission nebulosity east of Orion’s belt, covering some 600 × 300 arcmin. The Loop was first photographed in 1889 by W. H. Pickering, but became more famous when E. E. Barnard captured it in 1894, securing the eponymous name. Extraordinarily, part of the nebula had already been recorded visually by William Herschel in 1786; this section, known as Herschel Region 27, covers an elusive 90 × 30 arcmin. For observers, the relatively unremarkable open cluster NGC 2112 lies just to the east of the Loop and serves as a useful guide to locating it.

The most recent theories suggest the Loop formed from one or more supernova explosions in the Orion Nebula region, perhaps over two million years ago. The resulting ejecta impacted a dense area of the interstellar medium and were subsequently excited by the brilliant stars forming within the Orion Molecular Cloud. The complex is designated Sh2-276, being one of the many bright nebulae catalogued by American astronomer Stewart Sharpless (1926–2013). Sharpless recorded many H ii regions and produced his first catalogue, Sharpless 1, in 1953, with 142 entries. His second, Sharpless 2, was published in 1959 and contained 313 objects. Orion is rich in Sharpless objects from his second catalogue.

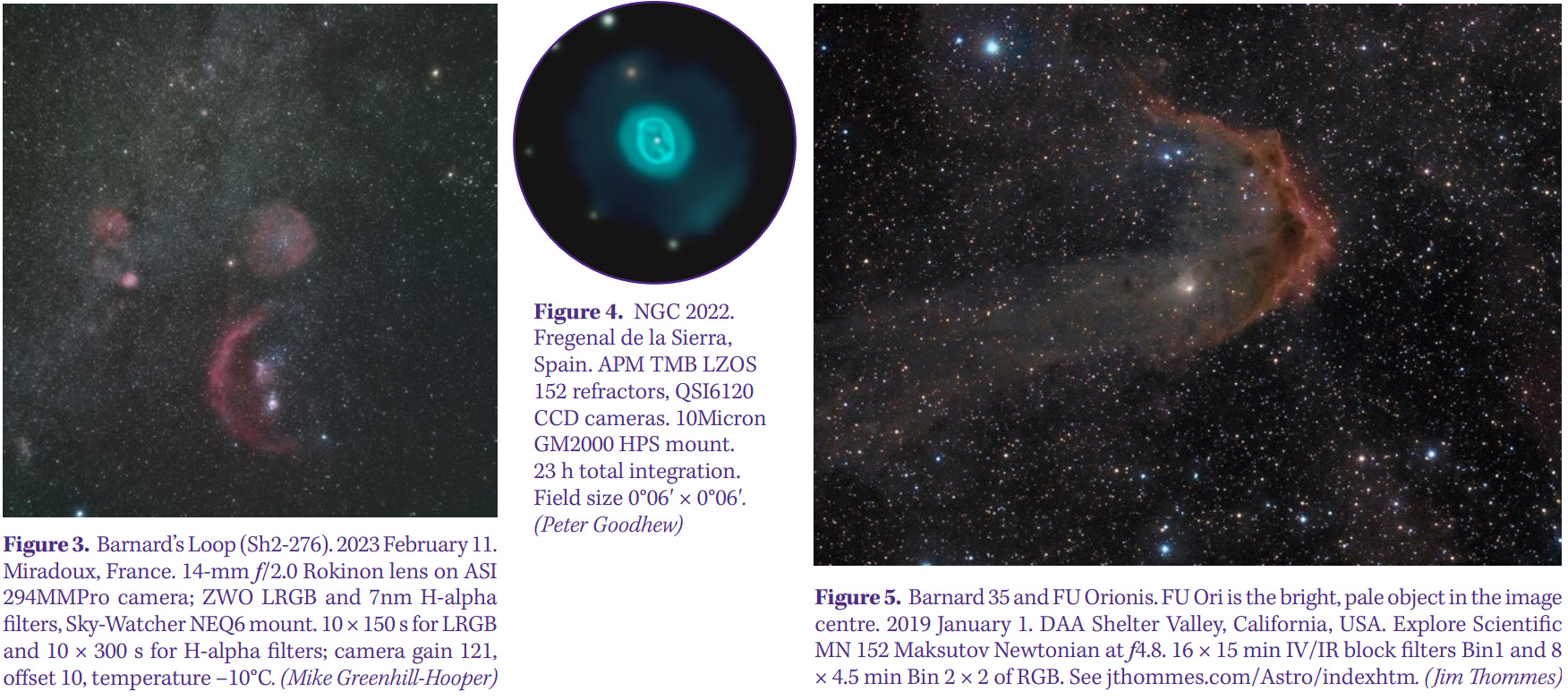

Moving north and west of Betelgeuse, the variable supergiant designated alpha Orionis, lies an area rich in interest. NGC 2022 (Figure 4) is an under-observed planetary nebula located along the imaginary line between Betelgeuse and lambda Orionis (Meissa); from there, phi1 and phi2 point to a greenish oval measuring 22 × 17 arcsec. Although its visual magnitude is 11.9, NGC 2022 has a high surface brightness, making it relatively easy to pick out. First observed by William Herschel in 1785, it is an early-phase planetary nebula. Its inner ring is straightforward to see, but the faint outer shell, extending 28 arcsec, is not. It requires a large telescope and high magnification to tease out subtle details, such as the slightly brighter southwest aspect.

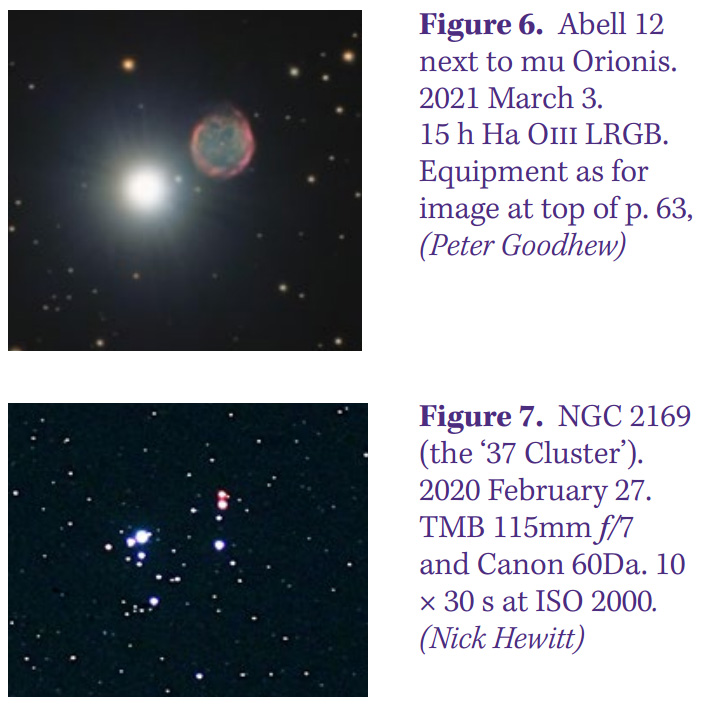

Less than a degree to the east of NGC 2022 is the dark nebula Barnard 35 and the fascinating variable star FU Orionis (Figure 5), which appear poised to be engulfed by Lynds Bright Nebula 878 (LBN 878). FU Orionis is a young star that erupted from obscurity to reach 9th magnitude in 1939; retrospective examination of earlier photographs shows it at magnitude 16. Unlike a classic nova, it has remained around magnitude 9 (V) ever since, confirming that it is not a nova. Much studied, FU Orionis is now known to be a binary star, variable in brightness as many pre-main- sequence stars are, and similar to a T Tauri star. Its activity is associated with Barnard 35, which has become more prominent as the system flared. Each component has an accretion disc, and material falling onto the stars results in the observed brightening. Like many young stellar objects, a small reflection nebula is also present, as seen in Jim Thommes’ image (Figure 5).

Drifting east and slightly north from Barnard 35 brings us to mu Orionis, where careful examination may reveal an annular planetary nebula lying remarkably close to the star. This is Abell 12, and mu Orionis (Figure 6) threatens to overwhelm it. Three other Abell planetary nebulae also lie nearby in this region of Orion: Abell 10, Abell 13 (top of p. 63) and Abell 14. Abell 11 was rejected from the catalogue after it was found to be a reflection nebula. These are challenging targets, best suited to experienced observers using large-aperture instruments.

After these difficult targets, it is worth refreshing the retina with a fun open cluster. NGC 2169 (Figure 7) is known as the ‘37 Cluster’, as it contains two stellar streams forming that number. It is bright at 6th magnitude but lies in a rich field, forming a triangle with nu and xi Orionis. This young cluster contains a neat double star, Struve 848, with components of magnitudes 7.5 and 8.1 separated by 2.3 arcsec.

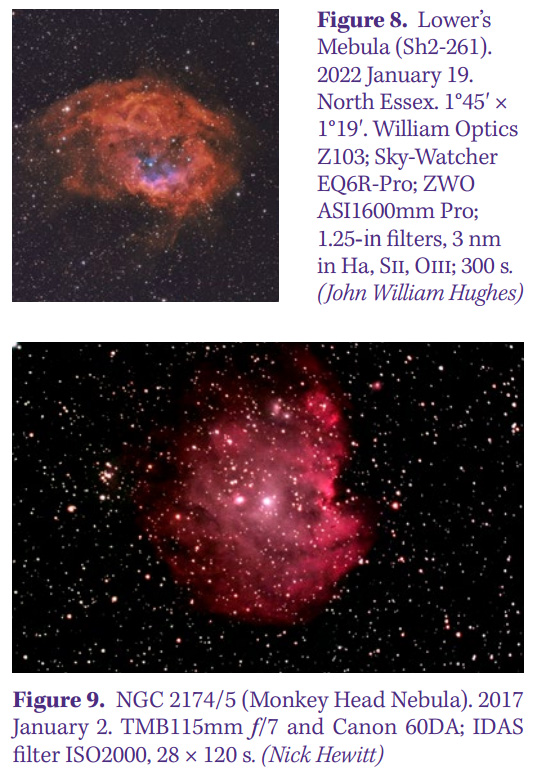

Another Sharpless entry can be found further north: Lower’s Nebula (Sh2-261; Figure 8), an emission nebula in northern Orion that is attracting increasing interest. Discovered in 1939 by father-and-son team Harold and Charles Lower, it has a low surface brightness but reveals impressive detail in narrowband images. Roughly twice the distance of Messier 42, it is illuminated by the high-velocity O-type star HD41997.

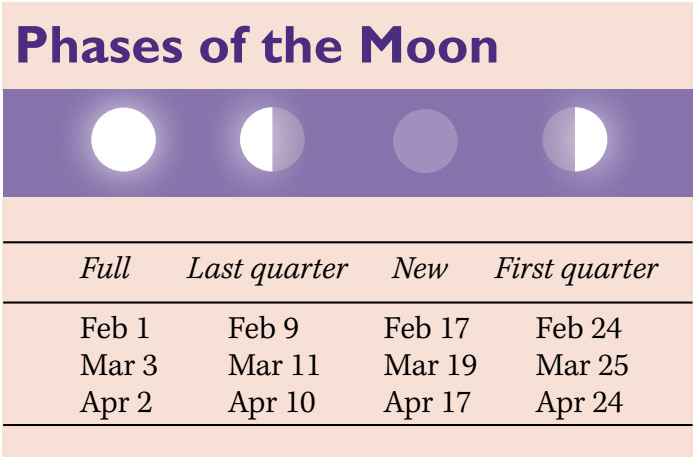

On the Orion-Gemini border lies the popular target NGC 2174/5, the Monkey Head Nebula (Sh2-252; Figure 9). The monkey’s visage is easy to discern in images, though some confusion has surrounded the nomenclature: the associated open cluster is designated NGC 2175 and the nebula NGC 2174, but the complex is best regarded collectively as NGC 2175. At magnitude 6.8, it is quite bright and pleasingly large at 18 arcmin. Venturing further north, across the border into Gemini, brings us to Castor’s left foot, eta (Propus), and mu Geminorum, with the supernova remnant IC 443 lying between them and the fabulous galactic cluster Messier 35 nearby.

While Orion has dominated the season, and indeed these Sky Notes, Ursa Major is now prowling into the northeast and beginning to swing around its smaller companion, Ursa Minor. If the Hunter is packed with nebulae and clusters, the Great Bear is a paradise for galaxy hunters and becomes increasingly prominent through March and April. Some of late winter’s finest galaxies are on show, with Messiers 81, 82, 101, 108 and 109 being perennial favourites, along with the large, old planetary nebula Messier 97, the Owl. All remain well placed into April and May, so there is no need to rush!

The solar system

Moon & Sun

The Sun is expected to remain active through 2026 and climbs higher in the sky as the year progresses. An annular solar eclipse on February 17 will not be visible from the UK, nor from anywhere else convenient, with the maximum eclipse occurring over Antarctica. Roll on the next solar eclipse, on August 12.

A total lunar eclipse occurs on March 3, but none of it will be visible from the UK. Observers in the USA will see it at Moonset, while it will be visible at Moonrise from southeast Asia and Australia.

Planets

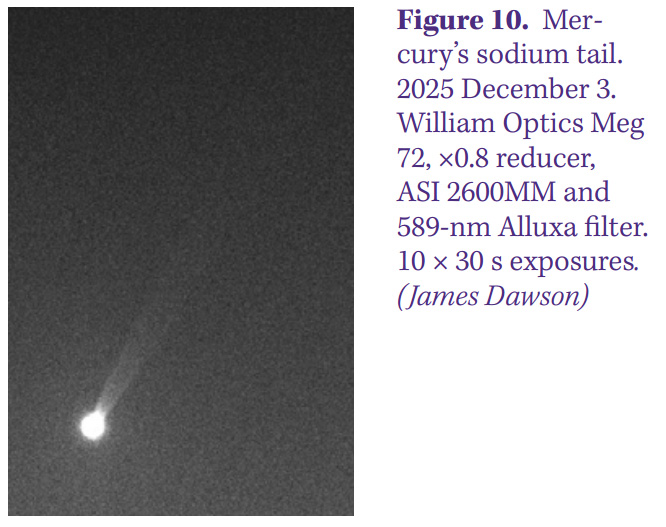

Mercury makes an appearance low in the southwest after sunset in February, reaching eastern elongation on February 19. This will be its best evening showing of the year and offers another opportunity to capture the elusive sodium tail (Figure 10). Although still just visible in early March, it will be very low to the right of Venus and, at magnitude 2, a tough target. Mercury reaches inferior conjunction on February 7; as it passes north of the Sun, great care is needed if attempting observations around this time. On February 19, a very slender crescent Moon lies northeast of Mercury, with Saturn positioned to the east of the Moon.

Venus is unobservable throughout February, being too close to the Sun. It sneaks into the evening sky in March but is very low.

Mars will be impossible to observe in February following its January conjunction.

Jupiter will remain the best of the planets for evening observation, shining brilliantly in Gemini through February and March.

Saturn has become too low now, dipping into the evening gloaming, and reaches conjunction with the Sun on March 25.

Uranus remains high in Taurus and well placed throughout February, remaining accessible during early March evenings.

Neptune is now too low for observation and reaches conjunction on March 22.

(1) Ceres lies in Cetus, northeast of Saturn, but is extremely low and – at magnitude 9 – a very tricky target.

Comets

Comet 24P/Schaumasse reached perihelion on 2026 January 8 and is a morning object in February, moving from Boötes though Virgo into Serpens Caput. It is expected to fade by around two magnitudes over the month.

Comet C/2024 E1 (Wierzchos) could be good during mid-March evenings, climbing higher in the sky but fading as it moves rapidly from Eridanus into Taurus.

Meteors

There are no major showers in February or March.

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |