The 2022 western elongation of Venus

2024 February 8

A report of the Mercury & Venus Section (Director: P. G. Abel)

Analysis of the observations made by Section members during the 2022 western elongation of Venus is reported. Several interesting phenomena occurred during this time and we discuss our findings and conclusions here.

Introduction

Venus is the brightest of the inferior planets. The appearance of Mercury and Venus in our skies is markedly different from those of the outer planets, as they are never opposite the Sun and cannot be seen around midnight. Venus orbits the Sun once in 224.7 days (its sidereal period) and during that time it is either on the western side of the Sun and so visible in the morning sky, or on the eastern side as an evening object.

On 2022 Jan 9, Venus passed through inferior conjunction and was located between the Sun and Earth. This marked the end of the previous eastern elongation and the start of the 2022 western elongation.1 Venus returns to the exact same position every eight years – this is called its synodic period. Therefore, the 2022 western elongation was very similar in circumstances to that of the 2014 western elongation, which was reported in the Journal.2,3

In general, the morning elongations of Venus are less observed than the evening ones – this trend continues but the 2022 western elongation did see 20 dedicated Section members submit regular observations to the Director. I would like to thank them for their hard work – their observations allowed long-term monitoring of the planet throughout the elongation and made this report possible. Observers who contributed are given in Table 1; a ‘V’ denotes visual observers.

As we shall see, the elongation was interesting and several intriguing phenomena were observed. During this time, two issues of Messenger (the Section newsletter) were produced and communicated to Section members.4,5

Inferior conjunction

The time of inferior conjunction saw poor weather in the UK and much of Europe. Consequently, no observations of inferior conjunction were communicated to the Director. However, the ALPO (Association of Lunar & Planetary Observers) Japan website is an excellent repository for amateur observations of the planet,6 and their Venus archive contains images taken during inferior conjunction by two observers. Minagawa recorded extensions of some 12.5° on each cusp, and images by Akutsu show similar cusp extensions.

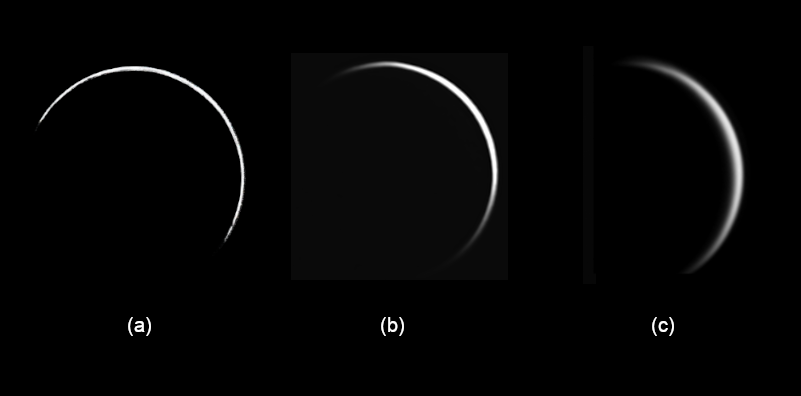

The first observations received by the Director were taken by Massimo Giuntoli on 2022 Jan 11, two days after inferior conjunction. Peter Tickner sent an image of Venus taken another day later. These observations are shown in Figure 1 and in both cases, the very slender crescent of Venus shows no abnormalities.

Cloud markings & bright spots

For visual observers with a sensitivity towards the bluer end of the spectrum, the cloud markings of Venus take the form of diagonal streaks, ‘Y’ or Ψ markings, and bright spots. Many of these features were recorded by visual observers (Figure 2).

The most striking and complex cloud formations in the Cytherean atmosphere are visible in the ultraviolet (UV) and frequently captured by digital observers using UV filters. These can be seen clearly in the UV images (Figure 3).

Another phenomenon associated with Venus is the appearance of small bright spots. Clyde Foster recorded a number of these from March into early June; Mark Lonsdale and Nick Haigh imaged many of them at the same time as Foster. Most of these brilliant white spots are located on the limb of the planet, and sometimes seem to spread inwards creating bright streaks (Figure 3).

(Log in to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |