The brighter comets of 2020

2023 December 12

A report of the Comet Section (Director: N. D. James)

This report describes and analyses the observations of the brighter or more interesting comets at perihelion during 2020, concentrating on those for with visual observations were obtained. Magnitude parameters are given for all comets with observations. Any evolution in the parameters of those periodic comets with multiple returns is discussed. Additional information on the comets discussed here, and on others seen or at perihelion during the year, may be found on the Section’s visual observations web pages.

Introduction

100 comets or potential comets were assigned year designations for 2020, while 47 previously numbered periodic comets returned to perihelion. 227 comets found by the SOHO satellite and one by STEREO were credited during the year. 187 of these were members of the Kreutz group, 25 of the Meyer group, one of the Marsden group, five of the Kracht group, and 10 not associated with any known group. Three of these objects were given a designation (2020 F8, P4 and X3). Three Marsden-group comets returned to perihelion and therefore could be numbered. There were five possible amateur discoveries (2020 A2, G1, J1, O2 and Q1) for which Masayuki Iwamoto, Eduardo Pimental, the SONEAR team, Leonardo Amaral, and Gennadiy Borisov may gain the Edgar Wilson Award, though there has been no formal announcement to date. The last awards were made for 2014.1 20 periodic comets were numbered during the year. Two comets were reported as visible to the naked eye during the year (2020 F3 and F8) and eight others reached binocular brightness.

The remainder of this report covers only the comets that were at perihelion during the year. When periodic comets have visual or electronic observations at five or more returns and have not previously been analysed in detail over the past decade, the secular behaviour of the comet is considered, even though it may not qualify as a ‘brighter’ comet during the present return. Any evolution in behaviour is of interest, as is observation of a steady state.

Orbital elements for all the comets discovered and returning during the year can be found on the JPL Small-Body Database Browser,2 which will also generate ephemerides. Discovery details and some information for the other comets found or returning during the year are available on the Section visual observations web pages,3 which also contain links to additional background information. The raw visual observations for the year are on the visual observations web pages in ICQ format and in the Comet Observations database (COBS).4 The full dataset from COBS is used for the multi-return analyses presented here, but otherwise only those observations submitted to the Section – through the visual observations co-ordinator or through COBS – are included, as well as all observations submitted to The Astronomer magazine. Additional images of the comets are presented in the Section image archive.5

The comets given a discovery designation

2017 T2 (PanSTARRS)

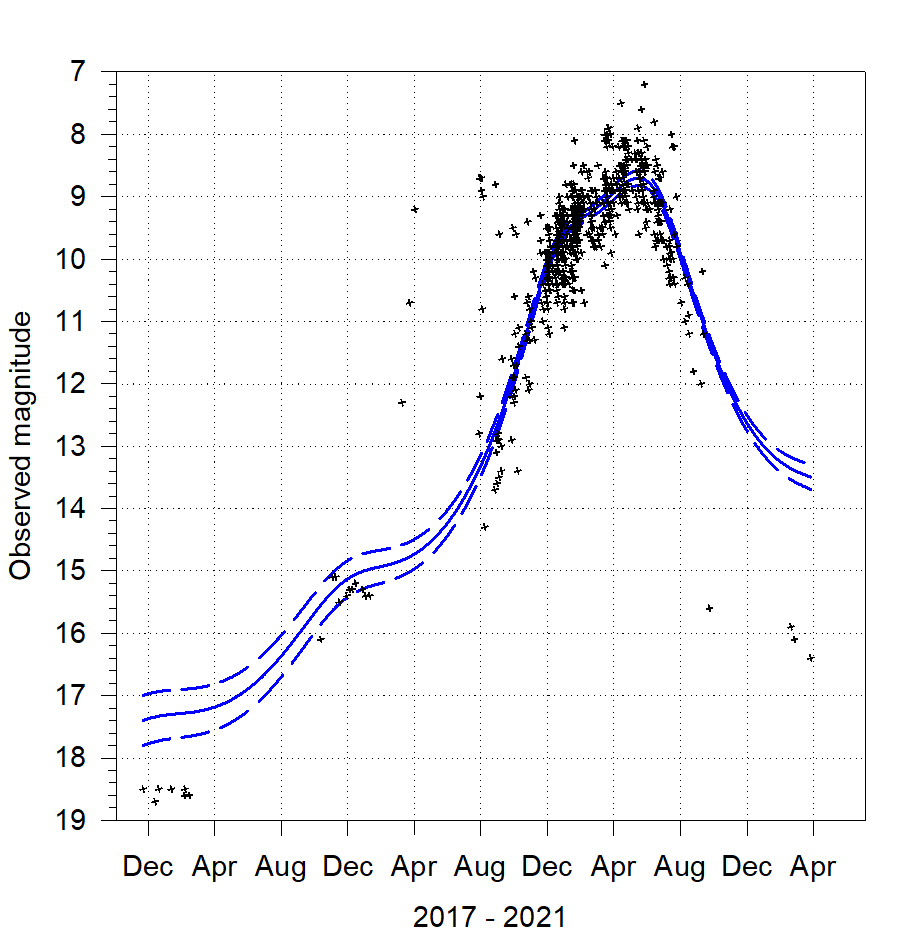

A 20th-magnitude comet was discovered in Pan-STARRS 1 images taken with the 1.8m Ritchey–Chrétien on 2017 Oct 2.52. There were pre-discovery Pan-STARRS images from Sep 15. [CBET 4445, MPEC 2017-U180, 2017 Oct 25.] The comet was at perihelion at 1.6au in 2020 May.

J. Gonzalez picked it up visually in 2019 March, roughly in line with the magnitude expected if the electronic observations were corrected for aperture. He recovered it after solar conjunction at the end of July, when he estimated it at 9th magnitude, roughly in line with that expected from the previous observations. Visual magnitudes have historically been brighter than those reported from images, and visual observers often see a larger coma diameter, so this seemed plausible. However, subsequent observations did not confirm the early visual estimates, which lie much above the mean light curve. The comet was, however, bright enough for observation with large binoculars for most of the first half of 2020. The peak brightness was around 8th magnitude.

After June, the comet faded and moved into solar conjunction. It should have been a relatively easy target for more southerly-located imagers during much of 2021, but no results were reported to the Section and there are only three estimates in the COBS database. This suggests that the comet rapidly ‘switched off’ in 2020 September, with a sudden fade of four magnitudes, which is quite unusual behaviour. There are also signs of a similar ‘switch on’ in 2018. There have been no further observations since 2021 March, although even taking the fade into account it should have been within range of imagers.

2019 U6 (Lemmon)

The Mt Lemmon Survey discovered an object of 21st magnitude in images taken with the 1.5m reflector on 2019 Oct 31.43. [MPEC 2019-V131, 2019 Nov 8.] It was given an A/ designation at the time, as it did not show any evidence of cometary activity but was on a clearly cometary orbit. Several observers subsequently reported that they had detected a cometary appearance in images. Michael Mattiazzo imaged it on 2020 Mar 11, when it showed a clear coma. With reports of activity made from December onwards, it was therefore reclassified as a comet. [CBET 4735, MPEC 2020-F136, 2020 Mar 25.]

The comet was at perihelion at 0.9au in 2020 June. It brightened quite rapidly and reached 6th magnitude around this time but began fading sooner than expected from a standard light curve. A linear light curve, peaking some nine days before perihelion, is a better fit to the observations. The comet became visible to UK observers towards the end of July, by which time it had faded to 9th magnitude.

2019 Y1 (ATLAS)

An 18th-magnitude object was discovered in images taken with the 0.5m Schmidt at Haleakala on 2019 Dec 16.23 by the ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) team. Confirmations came from several amateur observers. [CBET 4708, MPEC 2020-A72, 2020 Jan 5/6.] The comet was at perihelion at 0.8au in 2020 March. Maik Meyer suggests that it is a member of the ‘Liller’ family of comets, which includes 1988 A1 (Liller), 1996 Q1 (Tabur) and 2015 F3 (SWAN). The orbit has an Earth minimum orbit intersection distance (MOID) of 0.083au.

A visual observation from Alan Hale suggested that it was already around 13th magnitude in mid-January of 2020. For UK observers, it became an evening object from mid-February and moved northwards, so that it was circumpolar by April. Stephen Getliffe was the first UK observer to report observations, finding it at 11.6 in his 11cm reflector on Feb 11. Mike Collins reported it at 9.1 in his 25cm Schmidt–Cassegrain on Mar 20. On Apr 19, when it was near its brightest, Jonathan Shanklin found it an easy, well-condensed object of 8th magnitude in 20×80 binoculars from central Cambridge. It faded during May and June, though there is some disagreement between observers on the rate of fading, particularly in June where the observations are much brighter than the mean curve.

The observations are not well fitted by a standard light curve, but can be fitted by a linear light curve, peaking 19 days after perihelion. However, during the first half of April, the observations are generally fainter than the mean curve, whilst in the second half they are brighter. In addition, the degree of condensation (DC) reported after mid-month was generally greater than that noted earlier. Together, these points suggest that the comet experienced a significant increase in brightness of around 1.5 magnitudes on about Apr 16 and declined over about a fortnight. Ignoring this period suggests that, overall, the comet peaked in brightness 15 days after perihelion, but is otherwise moderately well fitted by a linear light curve.

(Log in to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |