The Revd George Fisher (1794–1873) – Arctic Astronomer

2022 December 8

The Revd George Fisher (1794–1873) started his career at an insurance company, but came to the attention of Royal Society members and studied at Cambridge University. Whilst still a student, he took part in a naval expedition to the island of Spitsbergen, in the Svalbard archipelago. After graduating, he became a naval chaplain and was chaplain and astronomer to Parry’s 1821–’23 expedition to find the Northwest Passage, for which he won the Arctic Medal. His career as a chaplain-scientist in the navy continued until 1834, when he retired to become headmaster of the Greenwich Hospital School, where he built an observatory. His retirement was to Rugby, which is how the author (a Rugby resident) came to be interested in him.

Introduction

In 2017 April, I gave a talk to Market Harborough Historical Society (MHHS) in Leicestershire about the Revd Dr William Pearson, co-founder of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) and rector of South Kilworth, about whom I have written much in the Journal and elsewhere.1

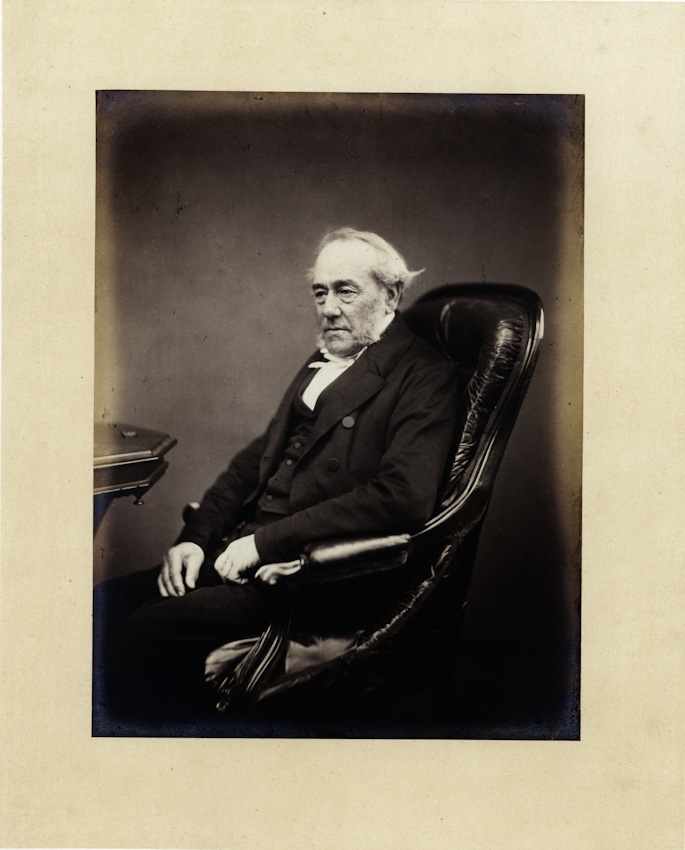

Bob Hakewill, a long-standing member of MHHS, had brought along some research notes about a local man with astronomical connections. His notes concerned the Fisher family, including the Revd George Fisher (Figure 1),2 who was buried in Little Bowden, now a district of Market Harborough. Surprisingly, it turned out that Fisher also had a connection to Rugby, where I live, although Bob did not know the town was my home. Fisher retired to Rugby in 1863 to live with his daughter in 11 Hillmorton Rd, close to the town centre and Rugby School. The house still exists and is part of an elegant terrace (Figure 2). The census of 1871 records five residents at this address:3

George FISHER Head WIDR 77 Retired Chaplain Royal Navy MDX Sunbury Alice FISHER D UM 31 KEN Greenwich Hester HILL Servant UM 21 Cook Domestic Servant DBY Tibshelf Elizabeth MALIN Servant UM 19 Housemaid Domestic Servant WAR Rugby Sarah ROWLEY Servant UM 23 Housemaid Domestic Servant LEI Peckleton

D stands for ‘Daughter’, WIDR for ‘Widower’, and UM for ‘Unmarried’. MDX, KEN, DBY, WAR and LEI refer to county of birth – Middlesex, Kent, Derbyshire, Warwickshire, and Leicestershire.

Usually, I would not take a research interest in someone who had a family connection to Rugby but did their astronomy elsewhere. For example, the recently deceased 14th Astronomer Royal, Sir Arnold Wolfendale, was born in Rugby,4 but his family moved north shortly after, so there is little else to link him to the town. However, Fisher’s astronomical career was so extraordinary that it is worth making an exception in this case.

Early life

Fisher was born on 1794 July 31 in Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex, and baptised there on 1794 Oct 2.5 He was the son of James and Henrietta Fisher. James was an architect, who surveyed Hanover Square in Mayfair, London. This elegant square was originally the site of prestigious homes but is now surrounded primarily by offices.

James unfortunately died around 1797, and Henrietta had to bring up the family on her own. This may explain why, at the age of 14, George joined the Westminster Fire Office. Despite its name, this was an insurance company, specialising in insurance against fire damage. Curiously, they did have a Company Fire Brigade, presumably to protect their customers in the city of Westminster and reduce their insurance pay-outs. George was part of this fire brigade and was awarded medals for his role.6 (See Figure 3.)

In 1817, Fisher matriculated to St Catherine’s College, Cambridge. It was not usual for an insurance clerk to secure a place at university, but the RAS obituary for Fisher suggests that he had already come to the attention of the scientific community.7

‘His strong mathematical and scientific tastes had already declared themselves [at the insurance company], and such occupation as his must necessarily have been distasteful to him; yet when after some years he left it for work more in accordance with his inclinations, his employers gave substantial testimony to the respect which his diligence and devotion to duty had earned from them.

‘The ardent desire for knowledge, which never in extreme old age deserted him, now brought him into contact with men of distinguished rank in the scientific work to whom he would otherwise have remained unknown, and the names of Sir Joseph Banks, Sir Humphrey Davy, Sir Everard Home, with many others, were always gratefully mentioned by him as having noticed with kindly sympathy and generously fostered his early love of science.’

In any case, he was unable to complete his undergraduate degree in a timely manner. Fisher, a 24-year-old undergraduate, was appointed astronomer to the polar expedition of 1818, headed by David Buchan. At this time, it was still believed that there was a polar ocean, largely free of ice during the summer, which could provide a route across the pole to the Bering Strait. The Royal Society’s ‘Committee for ascertaining the length of the Seconds Pendulum’ met on 1818 March 26 to organise the expedition:

‘The expedition received directions to touch at Spitzbergen if practicable in order that important geographical observations be made in that high latitude provided no land be found nearer the pole.

‘Mr George Fisher who has considerable mathematical talent to accompany the polar expedition to conduct scientific observations and experiments.’8

Unfortunately, it was not a successful voyage. The expedition ships, Dorothea and Trent, suffered severe storm damage and were unable to travel beyond Spitsbergen. Nonetheless, Fisher was able to determine the acceleration due to gravity at Svalbard by means of pendulum measurements, adding a data point to the ongoing investigations of the shape of the Earth.9

Fisher completed his Cambridge degree in 1821, earning a BA, although his RAS obituary noted that illness hampered him during his final examinations.10 An MA followed in 1825. In parallel, Fisher began his career as a naval chaplain in 1821, becoming a deacon in 1821 and a priest in 1827.11

The 1821–’23 Arctic expedition

Fisher was next invited to be the astronomer and chaplain on the polar vessel Fury (Figure 4) in 1821, on the so-called ‘expedition to the north pole’ of 1821–’23; it may more accurately be described as an attempt to find a route out of the Northwest Passage, to the north of Hudson’s Bay, into the polar ocean. The leader of this expedition was Sir William Edward Parry (Figure 5). Parry, interestingly, had astronomical interests and indeed has a crater named after him on the Moon. The entry for Parry in ‘Who’s Who in the Moon’, the BAA Historical Section Memoir, reads as follows:12

‘PARRY. Sir William Edward Parry, 1790–1855. (M)

‘English admiral and Arctic explorer. He accompanied Sir John Ross’s expedition (1818) for discovery of the N.W. Passage, and commanded an expedition himself in 1819, winning the Government prize when he crossed longitude 110°W. His record in reaching latitude 82° 45ʹ N. was unsurpassed for nearly fifty years. He was born at Bath, and died at Ems, in Germany.’

The (M) indicates that Parry’s crater was added to the Moon map by Johann Mädler and Wilhelm Beer in 1834–’46.

On his previous polar expedition, in 1820, Parry noted a previously undescribed feature of ice halos: the Parry arc (Figure 6). It is hoped that the reader is familiar with the beautiful circular halo which forms around the Sun, 22 degrees away from it, on a cold day when ice crystals with hexagonal symmetry scatter sunlight in our direction. The western and eastern edges of the halo correspond to parhelia, or sundogs, and sometimes there is a horizontal arc of white light joining them in the sky. Sometimes, too, there are extensions to the top of the halo. Very rarely, yet another arc, joining the extensions, appears above the halo, formed by refraction in long hexagonal ‘cylinder’ crystals whose axes and faces are both horizontal. This is the Parry arc.13

Fisher carried out many scientific experiments on Parry’s expedition. He had seven marine chronometers with him (Figure 7), three of his own and four on loan, which he rated against the local time by means of lunar observations (at sea) or meridional transits (on land). He carried out many measurements of atmospheric refraction and took a number of atmospheric samples which were later analysed to find their oxygen percentage. Samples which were stored at very low temperatures showed signs of the liquefaction of gases; this discovery pre-dated Faraday’s pioneering experiments in this field.14 Measurements of magnetic variations were taken, and of course there were many observations of the aurora borealis. Several of Fisher’s instruments (his telescope, microscope, magnetic dip circle and one of his chronometers; see Figures 8 & 9) are on display in the Polar Worlds gallery at the National Maritime Museum.15

Parry’s journal for the expedition is a great read.16 The party over-wintered twice. The first time was at Winter Island, in the Northwest Passage. Parry named the southeast corner of the island ‘Cape Fisher’. The party made contact with the local Inuit (who they referred to as ‘esquimaux’) and traded with them. In summer 1822, Parry explored the northern part of the Passage, finding a strong east-flowing current and following hints from the locals that a channel existed. Eventually he came across the Strait of Fury and Hecla, a narrow channel only a few miles across, which separates the North American continent from the immense Baffin Island. This strait is the only channel out of the Passage. Unfortunately, the strait was still blocked with ice even in late summer, and Parry was unable to break through.

The two ships over-wintered a second time, near the Inuit settlement of Igloolik. They were intending to try to pass through the channel again in the next summer, but had to abandon the expedition when the sailors started to come down with scurvy.

I have included a number of excerpts from Parry’s journal (missing out many others), to illustrate the wealth of astronomical and meteorological observations therein. Many entries feature Fisher. The quoted passages are reproduced verbatim, with the original syntax and spelling.

p.39: Wednesday, 1821 Aug 15

The aurora borealis was visible during the whole of the night, consisting of many luminous patches, or nebulae, having, when viewed together, a tendency to form an arch, and extending from south by east to south-west, its height in the centre being 15 degrees. From this arch, pencils of rays shot upwards towards the zenith. It differed from any other phenomenon of this kind, that I have seen, in being at times a beautiful orange colour.

p.66: Monday, 1821 Aug 27

Returning on board at 11 A.M., I found that the state of the weather had prevented any observation of the eclipse of the Sun which took place this morning; and Mr. Fisher could only just perceive the penumbra passing over it. [sic]

p.132: Tuesday, 1821 Oct 13

About the time of sunset this evening the sky presented a most brilliant appearance, the part next the horizon for one or two degrees being tinged of a bright red, above which was a soft light blue, passing by an imperceptible gradation into a delicate greenish hue.

p.133: Friday, 1821 Oct 23

The frost-smoke was today extremely dense, rising about a degree above the horizon, so as to completely obscure objects at that height, and at the distance of three or four miles. As the winter advanced this occurred to a greater extent, the cloud being more dense, and also rising higher whenever there was any open water in the offing. It proved a considerable inconvenience to Mr. Fisher in the course of his observations in the winter, utterly precluding on most clear nights, which seldom happened but with a westerly wind, his obtaining a sight of low stars for the purpose of ascertaining refraction at small altitudes.

(Login or click above to view the full illustrated article in PDF format)

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |