What To Do If You Think That You Have Seen A TLP?

This depends upon whether you have seen a coloured patch, a brightening, a flash or lightness in a shadow, as there are many things which can trick observers. It also depends upon whether you have seen something visually or with a camera?

General Advice: Try rotating or changing eyepieces/camera to see if the effect goes away or changes position on the lunar surface. This can be a sure way of ruling out internal reflections. Always record the date and UT that you first spotted the suspect TLP, describe it, and how it evolved, and note the UT of when you decided it was no longer there. Sketches or images are most welcome in trying to understand what has been seen. If after checking for some of the artificial effects described below, (there is a flow chart for doing this in the appendix section of the Hatfield Lunar Atlas and the corresponding SCT edition) you still think that it is lunar in origin, then please contact me on: atc@aber.ac.uk or telephone me (any time) on 0798 5055 681 (or if outside the UK on +44 798 5055 681), and I will issue a TLP alert and encourage other observers to check out the feature concerned. We also have a twitter page on: https://twitter.com/lunarnaut which can be used to search for any recent TLP sightings.

Colour: Please check other lunar features, especially on contrasty edges, in order to see if they have colours in the same directions, with respect to edges or brightness gradients of where you first suspected an anomalous colour. Colours caused by atmospheric spectral dispersion generally worsen the closer the Moon gets to the horizon and look like the image to the right. Whereas colour from chromatic aberration in the optics is generally radial to the optical axis and will worsen towards the edge of the image.

An example of atmospheric spectral dispersion induced colour fringes on contrasty edges in an image.

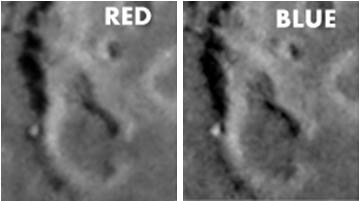

For visual observers, if you use red and blue filters, and switch (blink) between them, then if the colour is really present on the lunar surface then a blink effect will occur, i.e. bright in one filter and dark in another.

False effects in our atmosphere or telescope optics will not blink, but may cause some lateral displacement in the image. For colour images, try switching between red and blue or red and green channels to detect true colour effects on the lunar surface.

The same area of the Moon as seen through red and blue filters.

Note: that there is a slightly blue craterlet on the left side of the

large crater as it appears brighter in blue light than in red.

Finally, please note that although the Moon is generally grey to most of us, ray craters such as Aristarchus, can look slightly bluish to colour sensitive eyes, especially at low magnifications.

Aristarchus as showing a natural blue

Aristarchus as showing a natural blue

cast as imaged by David Darling

(ALPO) on 2004 Nov 25.

Brightenings: If you think a surface feature has brightened/darkened, compare it against similar sized objects elsewhere on the lunar surface over time. If imaging, then attempt time lapse, i.e. a picture every few seconds/minutes as this is a sure way of detecting localised changes. Small bright points can be easily affected by atmospheric seeing conditions, as this will blur them, perhaps making them more difficult to see. Larger objects such as crater rims, if blurred, can still be seen and will look the same in brightness. So always keep an eye on similar sized objects for comparison. Sometimes bright slopes emerging into sunlight may brighten up considerably as they catch the sunlight, but this is normal – so be warned and check against similar illumination photographs in an atlas or on-line.

Flashes: Unfortunately if you see a single flash from some point on the lunar surface, there is not a lot that you can do to confirm this as it could simply be a cosmic ray air shower radiation particle striking your eye, or the CCD camera. However with the latter, if you have been recording video, you can at least examine the individual frames and see how long it lasts for. A cosmic ray event will be generally much sharper than any point-like features elsewhere on the Moon and will last just a single image frame (TV field). Radiation events can sometimes look like a point, multiple points, and even irregular streaks, depending upon how the eye/camera has intercepted the cosmic ray air shower.

A cosmic ray air shower detection on

A cosmic ray air shower detection on

a CCD camera in this view of earthshine.

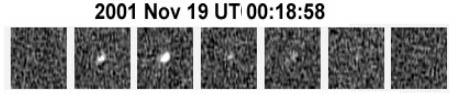

Impact flashes by contrast will have a seeing disk and fade over time, albeit perhaps quite rapidly.

A Leonid impact flash recorded on the Moon at 1/60th sec intervals.

If you see, or video a flash, on the dayside of the Moon, keep on watching/videoing as another cause of flashes can be from bright craterlets, just beyond the typical atmospheric seeing resolution, briefly coming into view for a fraction of a second, during occasional moments of good seeing. You can usually find out if this is the case because it may appear several times over several seconds or minutes. Yet another cause of flashes could come from sun glint from a satellite, or a distant aircraft strobe light. The former can be ruled out by checking for satellite passages, such as from http://www.heavens-above.com/ and the latter using web sites such as: https://www.flightradar24.com/ whilst observing. It is always worth noting the time, to the nearest second if possible, working out the precise location on the Moon, the duration of the flash, and its brightness compared to nearby bright points or stars. This is useful information if we want to compare your observation to someone else who was observing at the time.

Greyness in Shadows: Check nearby features, at a similar distance from the terminator, do they exhibit a similar effect? Could it be caused by seeing flare i.e. faint ghost images milling around, usually near to bright sunlit rims or mountains, which you can see projected faintly against shadows? Could it be caused by scattered light inside the crater from a sunlit rim, illuminating the floor weakly? Again check nearby features to see if they show similar effects. Otherwise record what you see and study how it develops over time. Is it more visible in different coloured filters? Is it stronger when using a Polaroid filter in different orientations? Is it more easily seen at high, or low magnification?

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |