Radio Telescopes

Radio telescopes, used for making direct observations of extra terrestrial objects, fall broadly into two distinct types, Total Power Receivers and Spectrometers.

Total Power Receivers

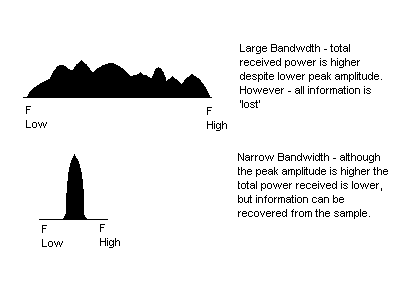

These instruments convert the sum of the entire received signal into a DC voltage that is then recorded and analyzed by the astronomer. The instrument is categorised by the bandwidth of the instrument, the larger the bandwidth (i.e. the frequency range from the lowest to the highest that can be detected), the more sensitive the instrument becomes – it can detect weaker signals. Conversely, apart from the power received, very little information about the signal can be recovered. The bandwidth of a total power instrument may be in the order of tens of MHz, perhaps even more.

In both examples above, the total power received is equivalent to the total area of the waveform (in black).

Spectrometers

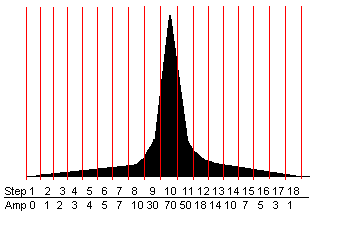

The other main type of radio telescope used by amateurs is a spectrometer. This type of telescope has a much narrower bandwidth, typically in the order of a few kHz. To perform a spectral analysis, the receiver is tuned from a low frequency to a high frequency at incremental steps and the amplitude of the received signal is recorded at each step.

This idealised image illustrates the sampled waveform as the receiver is swept from a low frequency to a high frequency and the logged amplitude is recorded. It can be clearly seen that stepping at a smaller intermediate frequency will enable a better numerical representation of the waveform to be recorded. Of course, this would be at the expense of the sensitivity of the receiver. It can also be seen that a spectrometer is a far more complex instrument than a total power receiver. This type of instrument is discussed further in the Hydrogen Line section.

A 12GHz Total Power Receiver

It is very easy to assemble a total power receiver for observing the sun using “off the shelf” satellite television components.

You will need a ‘Sky’ mini-dish aerial and LNB, a length of satellite specification coaxial cable, 2 ‘F’ connectors and a ‘Satellite finder’. You will also need a 15V (approximately) power supply capable of supplying 0.25Amps (250mA). All this is available from your favourite on-line auction web site for about £40.00.

Simply connect the Satellite finder to the LNB using the coaxial cable and ‘F’ plugs. The tricky bit is getting the power connected. The positive wire from the power supply needs to be connected to the inner core connector on the Satellite Finder (the receiver side) and the ground (0V) wire connects to the shield side. You can use crocodile clips, or simply poke and wrap the wires accordingly. Make sure that they don’t short out though.

Mount the dish on a short pole or tripod and point it at the sun. A small piece of silver foil glued to the very center of the dish will aid alignment. When the sun is correctly aligned, the reflection from the foil will appear in the center of the LNB cover.

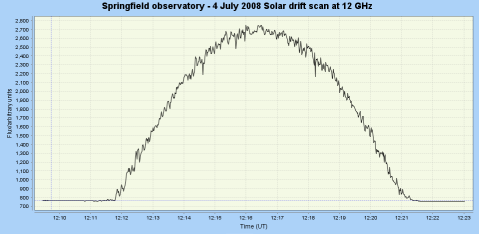

The dish aerial (assuming that it is an accurate parabola) has two attributes that are directly related to each other. Beamwidth and Gain. Radio waves are much longer than light waves. Consequently, a small dish aerial such as this cannot resolve a point source (like a star). The signal from a point source will rise to a peak and then fall as it passes through the beam of the aerial. A small aerial such as this, operating at 12GHz has a beam width (measured from where the signal is 50% of maximum, up to maximum and then back down again to 50% of maximum) of about 5 degrees. This is referred to by radio Astronomers as the FWHM value – Full Width Half Maximum. To improve the resolution, the size of the aerial needs to be increased. Doubling the diameter will quarter the beamwidth and will also quadruple the gain of the aerial. However, reducing the beamwidth will make the aerial more critical in alignment.

The signal from the sun will comfortably cause a reading on the Satellite Finder signal strength meter. Simply make a note of the time and the strength and plot the results on Graph paper.

A much better system is to connect a multi-meter with a recording output across the meter connections on the back of the meter. The recording multi-meter connects to your home computer using a serial (USB or RS232) connection and the software supplied will log the data (much more accurately) for you at a much faster data rate.It should also log the time as well. The data can be imported into a spreadsheet program such as Microsoft ® Excel and a graph produced from the data. This trace was produced by Andrew Lutley using a mini-dish a Satellite finder and a low cost logging multimeter and is a wonderful example of what can be achieved with very little outlay.

Incorporating a Dicke switch

The radio engineers 2nd biggest enemy is temperature. (Interference will always be number 1). Electronic circuits – especially those that amplify small signals are very susceptible to changes in temperature, even when carefully designed. A temperature change of a only a few degrees can cause major changes in the recorded signal.

During WWII, a radar engineer named Robert Dicke was suffering this problem. He wanted to be sure that the signal he was observing was what he thought it was. His solution was to switch the receiver between the aerial and a known source and then record the difference. Martyn Kinder is developing a modified LNB that will switch between the waveguide probe and a fixed value resistor. Details will be published here in the next few months.

https://britastro.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/123.PNG

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |