2022 December 4

Eight outbursts of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann in 3 weeks: a new record

Updated on 2022 December 7

Comet 29P/SW1 has been passing through the constellation of Gemini in recent weeks passing through its stationary point in October (see BAA Handbook, Comet Section entry and finder chart : link for BAA members only). By November 7, the coma around this centaur object had faded to its faintest for over 6 months, having previously exhibited a good number of mini-outbursts in recent months, none of which were brighter than 14.8R nuclear magnitude. So, the comet looked to be fading beyond visibility in an amateur-size telescope and that we were set for a quiet spell.

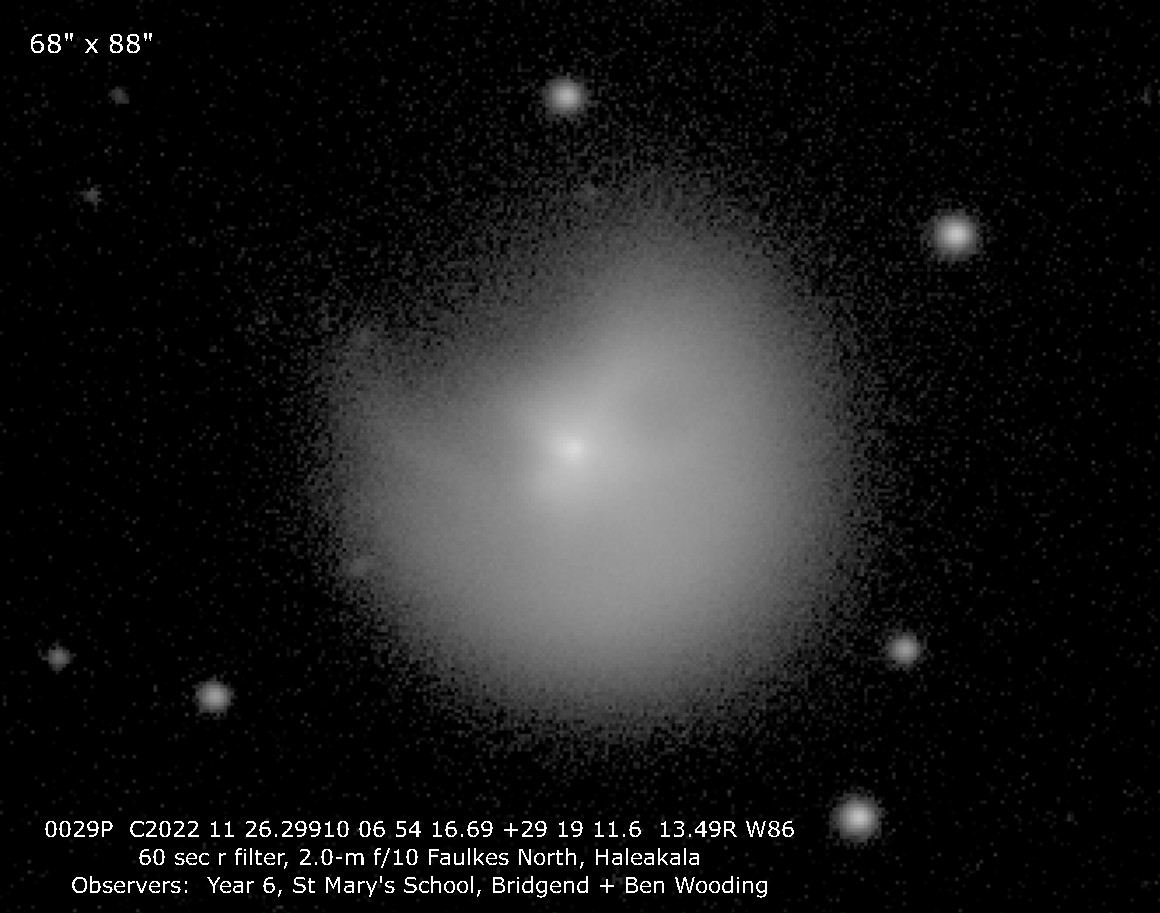

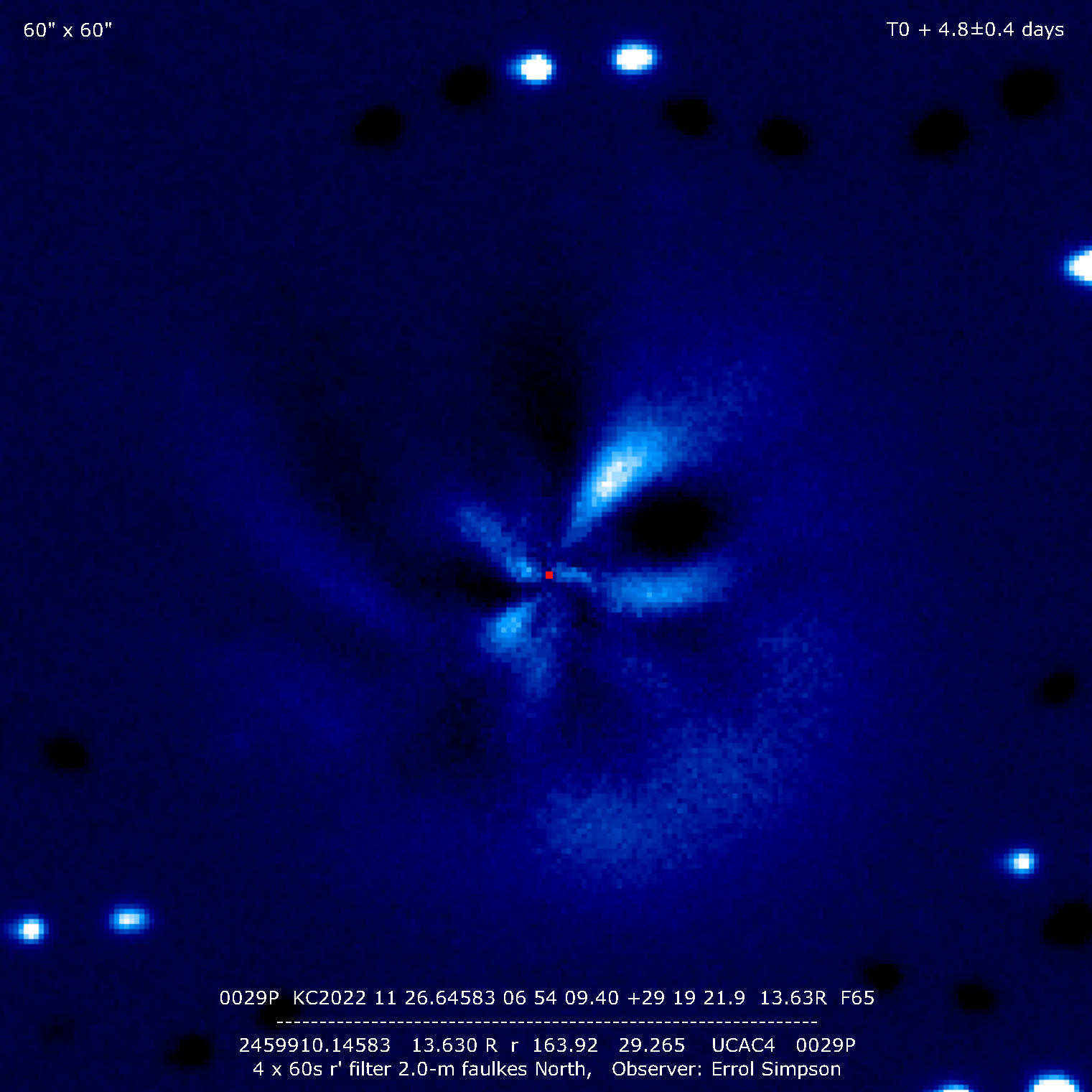

However, the next day this all changed when a new phase of intense activity on the nucleus started up. Since then, 5 mini-outbursts have taken place followed by 3 strong consecutive outbursts, one just reaching 11th magnitude on November 21.9. For their discovery, we thank the dedicated amateurs supporting the MISSION 29P campaign, and several schoolteachers and many children, typically aged 10-11, who work together in the classroom under the banner of the Comet Chasers Project. Their 29P observations these past few weeks have allowed us to follow 29P’s every move. Here are some views of it some 4-5 days post-outburst shining more than 160 times brighter than the nucleus alone.

The blue-white false-colour image (below) taken around the same time has been image processed with a 20° rotational gradient filter to show details of local outflows within the new expanding coma.

From the historical perspective, this remarkable behaviour is a continuation of the dramatic switch that occurred towards the end of 2021 September brought on by at least 4 strong outbursts in quick succession. Interestingly the last time such a switch in behaviour happened was almost 14 years ago in 2008 January when intense activity persisted afterwards for more than 2 years. Given 29P’s orbital period of 14.7 years, we may be seeing the onset of a repeat performance with more strong activity expected through to late 2023. So, plenty more surprises are no doubt in store.

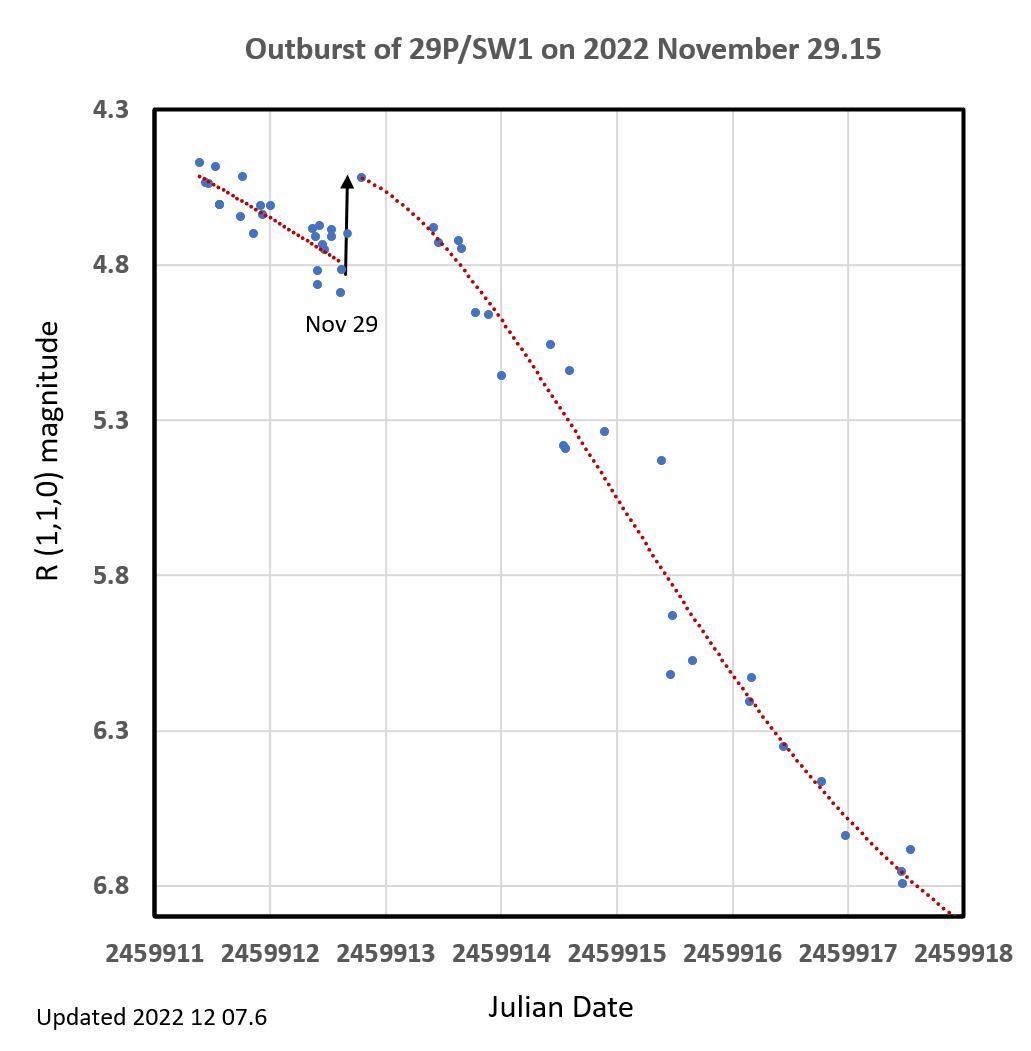

Although 29P can remain relatively quiescent for many months, more often than not when a strong outburst takes place, one or more further strong outbursts ensue within a week or two. Such ‘triggered’ outbursts are relatively commonplace with some 57% of all 93 strong outbursts detected in the past 12 years having this close association (median separation in time of ~5 days). The present revival of strong activity has fitted this pattern, it taking just 6 days before a second eruption made an appearance as can be seen from the lightcurve of the current apparition.

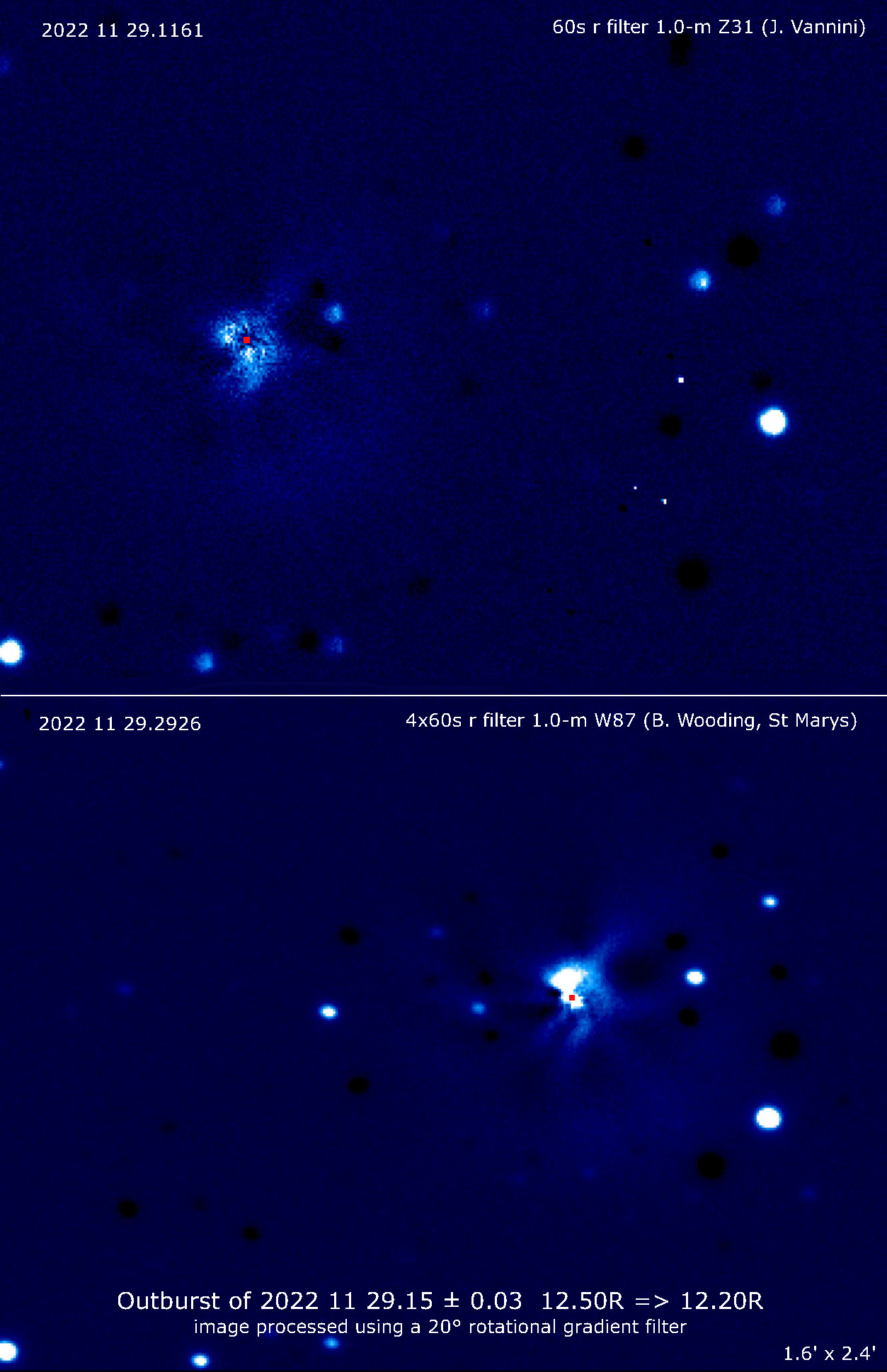

The comet then had another surprise for us. On November 29.113 and 29.116 in images taken by Peter Carson from Spain, and by Julio Vannini using a 1.0-m telescope of the Las Cumbres Observatory on Tenerife showed it had faded significantly. The next images by Dave Storey on the Isle of Man on Nov 29.170 appeared to show it brightening. Finally, on Nov 29.291 Ben Wooding and St Mary’s School, Bridgend (one of the classes taking part in ‘Comet Chasers’) obtained images from a 1.0-m LCO telescope in Chile that provided clear evidence of another outburst (intensity of ~30 nucleus-equivalents), confirmed by subsequent photometry as shown in this lightcurve plot.

When the Comet Chasers images were processed they revealed a new fan-shaped outflow that had extended to almost 11,000 km from the nucleus within 3-4 hours of the initial eruption indicative of speeds of up to 900 m/s (projected on the sky). The following two images show the before and after appearance of the inner coma.

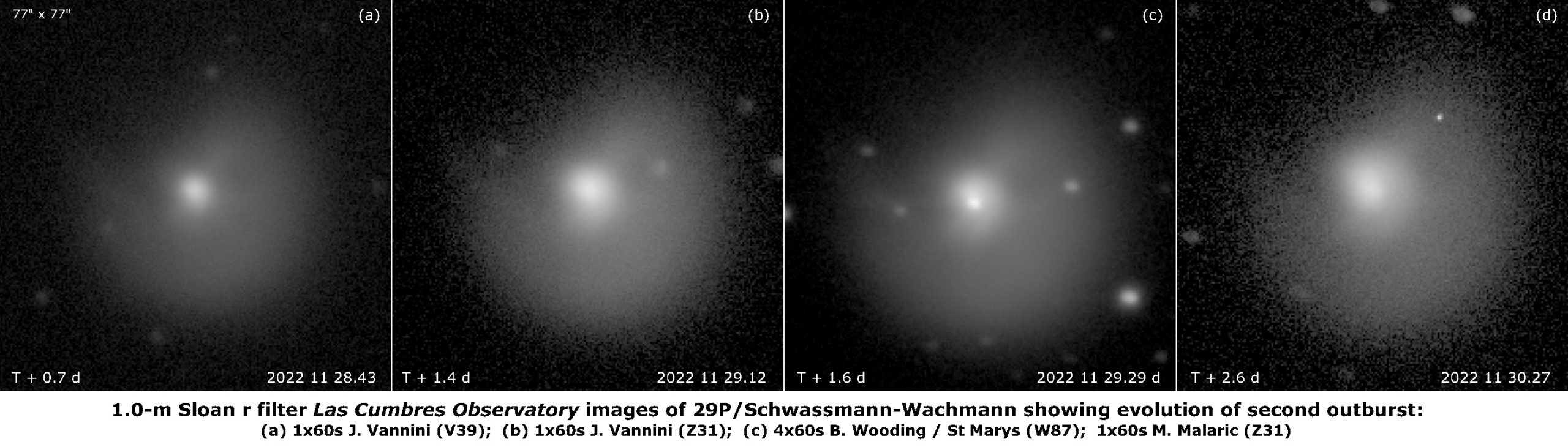

Such high-velocity ejecta have never been witnessed before, probably because such prompt observations have never been made following a strong outburst. POSTSCRIPT dated 2022 Dec 7: It turns out that the fan-shaped ejecta in the above image originates from the outburst of November 27.7 and not the third and last of the outbursts. The mis-interpretation arose in the rotational image processing that did not show the new feature owing to the poorer resolution and higher noise in that single image. If we look at the normal logarithmically stretched images the evolution of the second outburst is very evident.

The frequency of outbursts at 29P, with 8 events detected in just 3 weeks, and the existence of triggered strong outbursts as almost the norm, challenge the conventional thinking as to the origin of the activity in this object. The current Cometary Science Newsletter December 2022, Issue 93 contains an item that refers to the crystallisation of amorphous water ice ( a solid-solid phase transition) as the underlying energy source powering these outbursts. This is a very weak phase transition that only generates enough heat to raise the temperature of water ice from about 130K to 150 K whereas much more energy is required to convert any trapped hypervolatile gases such as CO from the condensed state to form gases that can escape into space. An alternative energy source proposed by this author aims to account for extreme cometary behaviour such as is seen with 29P.

Richard Miles

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |