2023 September 10

What will Comet C/2023 P1 (Nishimura) do?

A lot of items have been appearing in the media about this comet. As with most comets that come to public attention there is a lot of hype around. This comet is currently bright and it has a nice ion tail but, as it comes to perihelion on September 17, it will be at a very small elongation and so will be very difficult to observe.

The comet was discovered as an 11th magnitude, diffuse object, by the Japanese observer Hideo Nishimura on Aug 12.78 UT (CBET 5285). He was scanning the morning sky with a camera and telescope looking for comets that would have been hidden in the Sun’s glare and which therefore would have evaded the large surveys. When he found it the comet was at a fairly small solar elongation (34 degrees) which meant that it was quite a challenge to observe in the morning sky unless you had a very good eastern horizon.

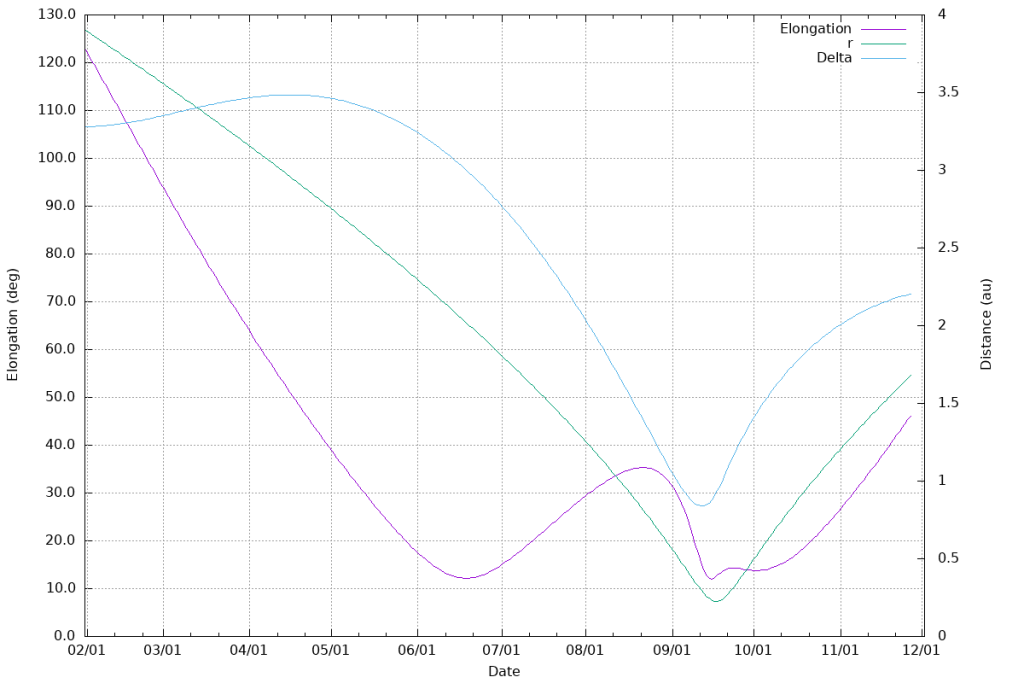

A number of observers managed to get astrometry of the comet and the preliminary orbit showed why it had not been picked up earlier. This plot shows the elongation of the comet using that orbit. The comet has been at an elongation of less than 40 degrees since the beginning of 2023 May and Nishimura discovered it as it reached around 34 degrees rising out of the morning twilight. For amateur comet discovers searching the morning twilight sky is a key tactic and the orbit of this comet was almost perfectly designed to avoid the surveys. The surveys could have picked it up back in April when the elongation was much larger but it was then over 3 au from the Sun and so would have been much fainter. The plot also shows the comet’s distance from the Sun (r) and distance from the Earth (delta).

In fact, CBET 5291 announced that Weryk reported his identification of pre-discovery stellar images of this comet in images obtained with the Pan-STARRS1 system on 2023 January 25, and Pan-STARRS2 on January 19 and 24 (both are 1.8-m Ritchey-Chretien reflectors at Haleakala), when it was between 21st and 22nd magnitude. The pre-discovery astrometry extended the observation arc considerably and this allowed Nakano to calculate an accurate set of orbital elements:

Epoch = 2023 Sept. 13.0 TT

T = 2023 Sept. 17.64148 TT Peri. = 116.29686

e = 0.9960880 Node = 66.83421 2000.0

q = 0.2251598 AU Incl. = 132.47647

The comet comes to a very close perihelion distance, q, of 0.225 au on 2023 September 17.6. The comet is periodic with a period of 437 years and it was last in the inner Solar System in 1588. There is no record of it being observed then. Interestingly, John Greaves (Northants) pointed out (CBET 5290) that this orbit is very similar to orbits of the meteoroids of the established meteor shower sigma-Hydrids (which is active during Nov. 22-Jan. 18).

This comet will have made many passes close to the Sun. Such old comets with low perihelion distances tend to have a very low dust/gas ratio. This probably means that we will not get a bright dust tail at perihelion. Observations so far are consistent with that in that the ion tail has been very impressive but there is very little evidence of a dust tail and amateur spectroscopy indicates a spectrum dominated by gas.

At discovery the comet was in Gemini. As it approached perihelion the elongation decreased but comet brightened rapidly and a spectacular and dynamic ion tail appeared. This tail grew in length and by September 7 it was 10 degrees in length, pointing away from the Sun.

The comet is now moving from the morning sky to the evening and the best chance of seeing it or its tail will be an hour or so after sunset from September 14 onwards. This will be an extremely challenging observation. Even if the comet is bright it will be only a few degrees above the western horizon in a very bright sky before the start of nautical twilight. If the tail is long it may be possible to image it sticking up from the horizon in a darker sky but you would need very transparent conditions to do that. We had something similar with the huge dust tail of C/2006 P1 (McNaught) in 2007 when the comet’s head was well below the horizon but we could detect the tail from the northern hemisphere. That situation was rather different in that it was a much brighter comet with a spectacular dust tail and we don’t expect much of a dust tail from this comet.

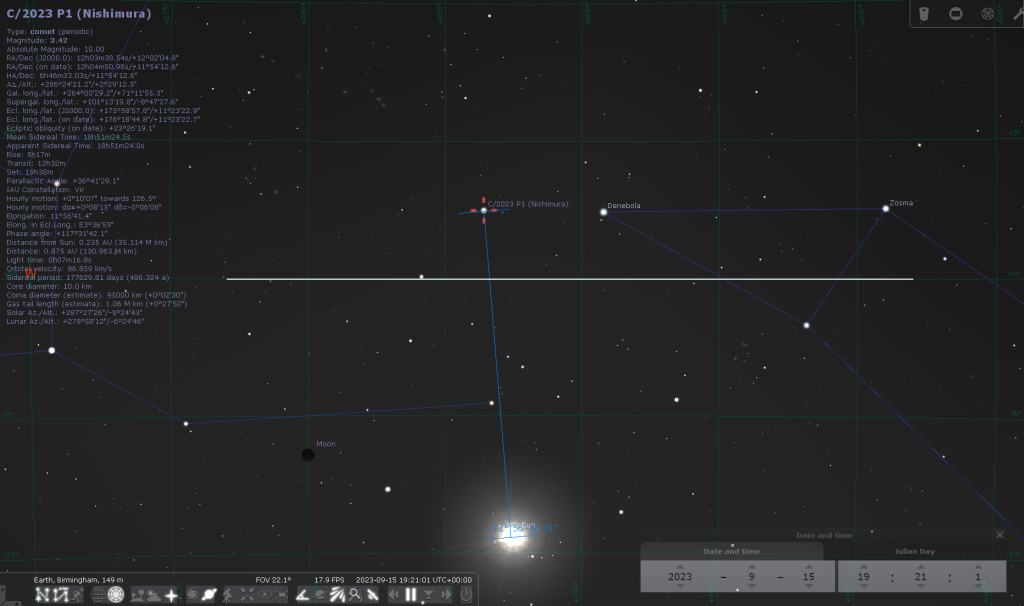

This plot from Stellarium above shows the situation on September 15 as seen from 52N. Bear in mind that this chart has the benefit of removing the atmosphere and the horizon but it shows how close the comet is to the sun. On this day the comet is directly above the Sun in the sky and at 1920 UT it is around 2 degrees above the horizon and the Sun is around 10 degrees below the horizon. The comet will need to be really bright to be visible but perhaps it will be. Assuming it survives it might reach second magnitude but we have no real idea how it will behave as it gets strongly heated at perihelion. If you can find somewhere with very transparent air and a very clear western horizon (a convenient mountain perhaps?) it would be worth scanning with binoculars or taking a lot of short exposures in that general direction and see if anything turns up. It is very unlikely to be anything spectacular but any observation you do make will be a a great achievement and scientifically interesting.

Post-perihelion, Mike Mattiazzo notes that the comet will enter the field of view of the HIA1 imager on STEREO-A on September 18 so that will be a chance for all of us to see it.

Images received by the section so far are in our archive here. If you do manage to observe it over the next few weeks please send your observations in to the section. This is going to be a real challenge and it probably won’t come to anything but you never know. That is what makes comet observing so much fun!

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |