Asteroids (and Dwarf Planets) – where are they ?

Introduction

All asteroids orbit our Sun, apart from the recent discovery of the interstellar visitor, 1I/2017 U1 better known as ʻOumuamua, which was found to be on a strongly hyperbolic orbit. Here we look at the nature of elliptical orbits and how they are described and measured. Depending on the region of space these orbits are located, asteroids are classified into the following general groupings:

– Near Earth Objects

– Main Belt Asteroids

– Trojans

– Centaurs

– Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt Objects

– Scattered Disk Objects

– Extended Scattered Disk Objects

Lists and definitions of these groups can be found on various websites e.g.;

Minor Planet Groups/Families – Bill Gray

Lists and Plots – Minor Planet Center

Asteroid and Comet Groups – Petr Scheirich. This is an excellent site with many diagrams and animations.

The XXVIth General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union was held in Prague 14th to 25th August 2006. Two resolutions were passed, but not without considerable discussion, relating to planets, asteroids and comets. The outcome of these resolutions is that the Solar System is now made up of Planets, Dwarf Planets and Small Solar System Bodies (ie; asteroids and comets).

For further details see ‘New Definitions for Solar System bodies’.

Orbits

Introduction

This section introduces and explains the terms used to describe an orbit. If you are of a mathematical bent and want to dig in to the depths of the subject then try one or more of these books:

Orbital Motion by A E Roy, published by the Institute of Physics

Solar System Dynamics by C D Murray and S F Dermott, published by Cambridge University Press

Fundamentals of Celestial Mechanics by J M A Darby, published by Willman-Bell

Orbital Elements – a definition

The path followed by an asteroid round the Sun (or that of any body around another), its orbit, can be described by the following six numbers plus the date (epoch) for which they are valid;

| Name | Symbol | MPC notation | Description |

| Mean anomaly | M | M | Although the true definition is a little more complicated this is essentially the current angular distance from perihelion to the present position of the asteroid measured in the direction of motion Semi-major axis |

| Semi-major axis | a | a | (Half ) the length of the long axis of the ellipse |

| Eccentricity | e | e | A measure of the deviation of the orbit from a circle (all asteroid orbits are ellipses).e = c/a |

| Inclination | i | Incl | The angle between the plane of the orbit of the asteroid and the ecliptic Longitude of the ascending node |

| Longitude of the ascending node | Ω | Node | The direction in space of the line where the orbital plane intersects the plane of the ecliptic. It is measured eastwards (increasing RA) from the Vernal Equinox (First Point of Aries) |

| Argument of perihelion | w | Peri | Defines how the major axis of the orbit is oriented in the orbital plane and is the angle between the ascending node and the perihelion point measured in the direction of motion |

| Epoch | Epoch | The date for which the values of the above elements are valid. |

The orbital elements listed in the table above are shown in the diagram below.

Distance of perihelion from the Sun, q = a(1-e). Distance of aphelion from the Sun, Q = a(1+e).

Distance of perihelion from the Sun, q = a(1-e). Distance of aphelion from the Sun, Q = a(1+e).

Orbital elements – an example

The orbital elements for the Near-Earth Object, 99942 Apophis, downloaded from the Minor Planet Center are shown below.

Minor Planet Ephemeris Service: Query Results

Below are the results of your request from the Minor Planet Center’s Minor Planet Ephemeris Service. Ephemerides are for observatory code J77 (Golden Hill Observatory).

(99942) Apophis

Epoch 2019 Apr. 27.0 TT = JDT 2458600.5 MPC

(2000)

M 163.22246 P Q

n 1.11234803 Peri. 126.68113 +0.87182264 +0.48924674 T = 2458453.76314 JDT

a 0.9225196 Node 204.05491 -0.46592547 +0.81337247 q = 0.7458888

e 0.1914656 Incl. 3.33688 -0.15112490 +0.31474251 Earth MOID = 0.00016 AU

P 0.89 H 19.2 G 0.15 U 0

The data that would need to be entered into an application such as Megastar to enable the track of the asteroid to be plotted is shown in bold underlined above. H is the absolute magnitude (the magnitude of an asteroid if it were 1 AU from both the Sun and the Earth) and G is the slope parameter.

Orbit diagrams (and other relevant data) can be viewed via the JPL Small-Body Database Browser page. Once the orbit diagram is displayed it can be run forward or backwards, zoomed in and out and the viewpoint altered from edge-on to above. An example of such a diagram for 99942 Apophis is shown below with additional explanatory notes added.

Referring to the diagram and table above and the orbital elements downloaded from the MPC;

| Epoch | Date shown at bottom left corner of diagram |

| Mean anomaly (M) | Angle F-Sun-M |

| Semi-major axis (a) | AP/2 |

| Eccentricity (e) | ((AP/2)-SP)/(AP/2) |

| Argument of perihelion (Peri) | Angle N-Sun-P |

| Longitude of the ascending node (Node) | Angle F-Sun N |

| Inclination (Incl) | To see this visit the JPL Small-Body Database Browser page, search for ‘99942’ and call up ‘Orbit Diagram’. Adjust the view to ‘edge-on’ by going to the Menu listing and selecting ‘Look from: Ecliptic’. |

Orbit determination

As soon as it becomes possible the Minor Planet Center computes the orbital elements for newly-discovered asteroids. These can be obtained by accessing the Minor Planet Ephemeris Service and an example is shown in section 2.0 above. However if you want to have a crack at this for yourself then Project Pluto, the producer of the planetarium software GUIDE, have provided a program, Find_Orb, for just this purpose.

How to use the software is described fully on the Project Pluto’s Find_Orb website. A very useful On-line Version of Find_Orb is now available.

Resonances

Asteroid orbits are affected by the gravitational interaction of asteroids with planets most notably with the gas giants. This interaction, or mean motion resonance, is most obvious where the orbital periods of asteroid and planet are whole number ratios eg; 1:1, 2:1 and 3:2. Beyond 3.5 AU from the Sun resonances work to contain asteroids within the resonant orbits rather than eject them as is the case with the Kirkwood Gaps in the Main Belt.

Mean Motion Resonances are described in detail in Tabare Gallardo’s website – Atlas of Mean Motion Resonances

Data sources

Orbital elements, data and orbit diagrams for specific asteroids can be obtained from several websites, viz.:

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) – Orbits

Minor Planet Center Comet and Ephemeris Service

Near-Earth Objects Dynamics (NEODyS-2) – NEO List

Asteroids Dynamics (AstDys-2) – Other Objects List

Asteroid Groups

Near-Earth Asteroids

Near-Earth Asteroids fall in to three classes, Atens, Apollos and Amors, named after the first asteroid to be discovered in each of those classes, i.e.:

2062 Aten (1976 AA)

Discovered on 7th January 1976 by E. F. Helin at Palomar and named after the Egyptian Sun god.

1862 Apollo (1932 HA)

Discovered on 24th April 1932 by K. Reinmuth at Heidelberg. Named after the god of the Sun, child of Zeus and Leto.

1221 Amor (1932 EA1)

Discovered on 12th March 1932 by E. Delporte at Uccle. Amor is the Latin name for the Greek Eros, the god of love.

Atens

Atens have a semi-major axis smaller than that of Earth (1 AU) and a aphelion distance of >0.9833 AU. The significance of these numbers is that at perihelion the Earth is 0.9833 AU from the Sun and at aphelion, 1.0167 AU. As can be seen from the diagram below (eccentricities exaggerated) Atens spend most of their time within the orbit of the Earth but can pass outside it.

There is a sub-set of Atens known as Inner Earth Objects (IEO’s) or Apoheles. All of the orbit of an IEO lies within that of the Earth and this makes them extremely difficult to detect. So not only must an IEO have a semi-major axis smaller than that of the Earth but both its aphelion (Q) and perihelion (q) distances must be less then the Earth’s perihelion distance (0.9833) as in the diagram below. However if the long axis of the orbits of the IEO and the Earth were to line up as shown in the diagram below the aphelion distance could be greater than 0.9833 but less than 1.0167 au.

Three IEO’s have been discovered to date (20th December 2004); 2002 JX8, 2003CP20 and 2004 JG6. 1998 DK36 and 2005 G31 may also be IEO’s.

Arjunas are asteroids with Earth-like orbits ie; low eccentricity, low inclination and a semi-major axis close to 1 AU.

There is a sub-set of Atens known as Inner Earth Objects (IEO’s) or Apoheles. All of the orbit of an IEO lies within that of the Earth and this makes them extremely difficult to detect. So not only must an IEO have a semi-major axis smaller than that of the Earth but both its aphelion (Q) and perihelion (q) distances must be less then the Earth’s perihelion distance (0.9833) as in the diagram below. However if the long axis of the orbits of the IEO and the Earth were to line up as shown in the diagram below the aphelion distance could be greater than 0.9833 but less than 1.0167 au.

Three IEO’s have been discovered to date (20th December 2004); 2002 JX8, 2003CP20 and 2004 JG6. 1998 DK36 and 2005 G31 may also be IEO’s.

Arjunas are asteroids with Earth-like orbits ie; low eccentricity, low inclination and a semi-major axis close to 1 AU.

Apollos

Apollos have a semi-major axis greater than that of Earth (1 AU) and a perihelion distance of <1.0167 AU. As can be seen from the diagram below Apollos spend most of their time outside the orbit of the Earth but can pass inside it.

Amors

Amor orbits lie between Mars and Earth (a>1.0 AU, 1.017<q<1.3) and are therefore Earth-approaching rather than Earth-crossing asteroids as are Atens and Apollos.

A plot of the Inner Solar System is shown here.

Mars crossers

This definition is courtesy of the MPML and Dr Alan Harris.

Asteroids which cross only the orbit of Mars have a quite long collision lifetime (of the order of the age of the solar system), whereas those that actually cross the Earth’s orbit have much shorter collision lifetimes, and also the time scales for major orbit modification (due to clse passes by the planets) are also much different. Thus on dynamical grounds it is important to distinguish between asteroids that cross only the orbit of Mars from those that cross the orbits of Earth and/or Venus. Therefore, in common usage, we usually do not include Amors (q < 1.3) or Apollos and Atens (which actually do cross the Earth’s orbit, in two dimensions) as “Mars crossers”, although most do actually cross the orbit of Mars as well. So in practical terms, objects that would be referred to as “Mars-crossers” would be those with 1.300 < q < 1.665. The dividing line between Mars-crossers and Amors is also arbitrary. The Amors don’t become dynamically active members of the “Earth-crossing population”

until around q < 1.1.

The first Mars-crosser to be so identified was 132 Aethra. It was discovered by James Craig Watson in 1873.

Main-Belt Asteroids

Location

The Main Belt of asteroids lies between Mars and Jupiter and stretches from approximately 2.0 AU to 3.3 AU from the Sun. The first asteroid, and first Main-Belt asteroid, to be discovered was 1 Ceres in 1801.

Gaps

Within the Main Belt there are gaps, where few asteroids are found, corresponding to various orbital period ratios with Jupiter ie; 4:1, 3:1, 5:2 and 2:1. The explanation for these was first given by Daniel Kirkwood hence they are known as Kirkwood Gaps.

The population of asteroids in the 2:1 mean motion resonance with Jupiter is described in a paper by Broz, Vokrouhlicky, Roig, Nesvorny, Bottke and Morbidelli. Asteroids in this region are classified as unstable, marginally stable (Griquas such as 1999 VU218) or stable (Zhongguos such as 2003 AK88). The stable asteroids are those with a dynamical lifetime (ie; they stay where they are) of the order of the age of the Solar System, the marginally stable ones, several hundreds of millions of years and the unstable variety around 10 million years. The paper suggests that the loss of the unstable asteroids from the region is balanced by an inflow due to the Yarkovsky effect on asteroids outside the resonance zone. If you really want to know more about the Yarkovsky effect than may be good for your health then try here.

Groups

Groups of asteroids within the Main Belt have similar orbital elements. Such groups are often referred to as Hirayama families named after K. Hirayama who first noticed this in 1918. Each family may have originated from a single larger asteroid which was broken up by a collision in the distant past. A diagram of many of the groups can be seen here.

Trojans

Trojan asteroids occupy the same orbit as their parent planet but are located around the Lagrangian L4 and L5 points, as shown in the diagram below. The vast majority of Trojan asteroids are associated with Jupiter but Neptune also has a small number. The first Trojan, 588 Achilles (1906 TG) was discovered in 1906. As of 2018 October 28, the Minor Planet Center listed 7039 Jupiter Trojans and 22 Neptune Trojans (these links will take you to the latest listings).

The Trojans oscillate or librate around the Lagrangian points as shown in this animation.

Centaurs

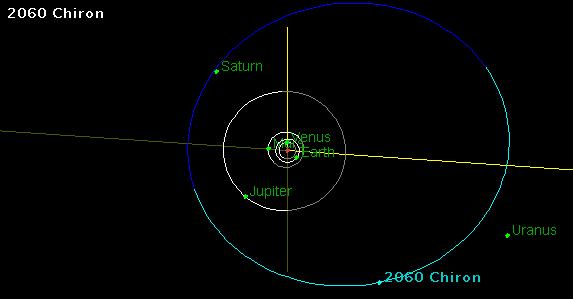

Centaurs occupy the region of the Solar System between Jupiter and Neptune having semi-major axis between 5.5 and 29 AU. At times they behave like comets being surrounded by a small coma of gas and at others like a common or garden asteroid – completely inert. Due to their large size (100’s of kilometers in diameter) and location they do pose a threat to life on Earth. They are subject to the gravitational influence of the giant planets and could have their orbits changed to such an extent that they are flung towards the inner Solar System (or, if we are lucky, out !). The orbit of the first Centaur to be discovered, 2060 Chiron in 1977, is shown in the diagram below.

A list of Centaurs can be found here and a plot of the Outer Solar System including them is shown here.

Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt Objects (EKBOs)

These objects (also known as Trans Neptunian Objects or TNO’s) can be sub-divided into;

– Plutinos

– Classical EKBOs

– Scattered Disk Objects (SDOs)

– Extended SDOs

Dave Jewitt’s Kuiper Belt webpage includes a comprehensive accounts of the various types of EKBO and other minor bodies and is well worth a visit.

Plutinos are objects which have similar orbits to that of Pluto in that they have a semi-major axis between 39 and 40 AU, a perihelion distance (q) less than or equal to that of Neptune and are in a 2:3 mean motion resonance with that planet. The first such object discovered, except for Pluto itself, was 1993 RO.

Classical EKBOs have semi-major axis between 42 and 48 AU and are sometimes referred to as Cubewanos, the first such object discovered being 1992 QB1 (15760). They occupy various resonances with Neptune i.e.; 5:3, 7:4 and 2:1.

SDOs, or Scattered Kuiper Belt Objects, are asteroids in highly eccentric orbits with semi-major axes greater than 48 AU.1996 TL66 (15874) was the first of these to be discovered. For more details, diagrams, etc. see here.

Extended SDO’s, also known as Inner Oort Cloud or Scattered Extended Objects, of which 90377 Sedna (2003 VB12) was the first discovered, exist at relatively large distances from the Sun and move in highly eccentric orbits.

To return to the All about Asteroids and Remote Planets page. Select here

To return to the Section home page. Select here

| The British Astronomical Association supports amateur astronomers around the UK and the rest of the world. Find out more about the BAA or join us. |